The Mystic

When I was little

My sacred space

Was a seat in the back

Of an old Toyota

On a Saturday morning

Loaded up with my Grampa,

Driving stick shift,

While strains of haunting melodies,

Blue notes and ragtime,

Floated out of

The old radio and mixed

With his stratchy hum

And a child’s off-pitch wail.

I remember my mosque

Was in the grass

Covered in dew,

Rolling down the hilltops

Before the storm,

And the wind

Tussling my long hair

And long dress

And the look of the clouds

As we waited

Waited for the rain

And in that moment

Of anticipation

I felt Allah in the wind.

When I was older

I learned about walls

About concrete

And about the feats

Of modern engineering

In the city

Where the grass was gray

But still I found religion

In the stucco slabs

And the tall glass windows

And the indoor plants

Where bamboo shoots rose

Tall as a tower

And called out to me:

Come pray.

Somehow it was religion

That brought me,

A small town girl with no

Particular relationship to God,

With no prophetic

Word to speak of

To the ancient halls

Surrounded by iron

Built out of red brick

Observed by the impartial

Eyes of a statue

Of a dead man

And first I felt trapped

I felt caged

I felt hollow

And then I found the dew drops

On the lawn at dusk

And I found that walls

Mattered not to God.

And it was in the basement—

Of a church no less—

No dome above me,

No light from a niche,

No platform from which

The Imam might speak

When I encountered the teachers

In the barest of places

Smoking cigarettes and carrying

Their lives on their backs

And asking for food

And before morning

Someone left a Qur’an

At the staff desk

And suddenly I knew

The direction

Of the Kaaba.

And while I know

I will find God

In the birds

And the city

And stuck in traffic,

I somehow know that

I must close my eyes

When the world gets dull

And the night drags

And something in me sleeps,

And then I can see

The miracle:

An old growth forest,

The line where the water ends

The ocean meets the sky

The cliff drops off

And I am a child

Sitting in the dew grass

Looking up at the sky

Admiring its endlessness.

I have been brought

This far.

The rest I must travel

On my own.

“The Mystic”

Week 13

Poetry

This poem, entitled “The Mystic,” draws not only from the final week of class but also from selected previous weeks and themes from throughout the course. It’s main inspiration, though, is from the penultimate lecture, Maryam Eskandari’s talk on sacred spaces.

Drawing from the in-class exercises, this poem emphasizes the individuality of sacred spaces. Rather than a prescription or blueprint for a sacred space, this poem explores the appearance of the sacred in more everyday situations, scattered throughout life.

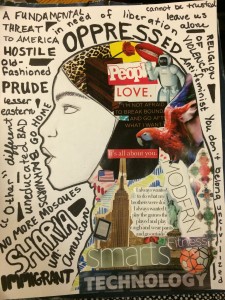

The poem makes references to several standard symbols and architecture of the mosque, including minarets, domes, minbars, and the qibla. However, the poem emphasizes that none of these traditional symbols exist in the sacred space, or else describes them in a subversive form, as when shoots of bamboo replace minarets. The speaker even implies that the idea of sacred spaces having walls is, initially, foreign. This ties in to Maryam’s theme that mosques, and sacred spaces more generally, need not conform to preconceived notions.

Similarly, the musical tradition is also subverted. In “orthodox” Islam, music is not allowed in sacred spaces; however, Aidi’s discussion the empowering role of jazz in the Afro-Islamic tradition reveals the important and arguably sacred nature of music. Therefore I included components of jazz (“blue notes” and “ragtime”) in the first stanza of the poem, challenging preconceived notions of a sacred soundscape.

For me, the concept of a sacred space is also fundamentally rooted in a mystical experience of Islam. Much like the quote we heard in class—

“Knowledge is like a horse. It can lead you to the gate of the palace, but it cannot follow you inside.”

—I believe that tradition can contribute to feelings of sacredness, but only individual, intuitive knowledge can define sacredness. This is evidenced by the last stanza of the poem:

“I have been brought / This far. / The rest I must travel / On my own.”

With this in mind, I decided to take an artistic risk with this poem: I wrote this poem largely about my own life. My grandfather’s pickup truck (stanza 1), miscellaneous scenes from my childhood (2-3), Harvard (4), and Y2Y (5) are among the more sacred spaces in my personal history.

While I am not Muslim, I chose to write a very personal poem for three reasons. First, I wanted to emphasize the importance of individual intuitive knowledge in constructing a sacred space. Secondly, I sought to highlight the transcendental nature of sacredness, in which one can experience the sacred feelings associated with “islam” while not being Muslim. Finally, I wanted to show that the concepts from class have themselves managed to transcend religious boundaries, so that I as a non-Muslim have still gained something very personally relevant from our discussions of sacredness.

Recent Comments