Prologue

May 2nd, 2018

Islam is a complex, multivocal tradition. This semester, I learned that there are perhaps as many islams as there are Muslims. Furthermore, religion—a human enterprise—is never separated from its practitioners. There is no “core,” or “unadulterated” Islam that transcends all the little islams lived out by individual Muslims. These practices themselves comprise Islam collectively. They all must be taken into account if we want a comprehensive understanding of the Islamic world. Thanks to this course, I have begun to understand the full breadth of this religious tradition, but I still have a long way to go. One semester is only enough to make a start. I scratched the surface, but the biggest lesson for me is that uncharted depths still remain.

I also learned that just as Islam is vast and diverse, so it is also a dynamic tradition. It has evolved over the centuries and continues to evolve today. This capacity for change contributes to the complexity of the tradition; every development in Islam provides a branching-off point from which numerous new perspectives can bloom. Religions, I have learned, are hardly static phenomena.

This fact flies in the face of Islamophobic ideologues, for whom it is convenient to think of Islam not only as univocal but also as unchangeable. This monolithic, static conception of Islam has never been Islam’s reality. Even as the Qur’an itself was dictated, its message developed. Some of its later verses contradict earlier verses, perhaps because they indicate responses to increasingly specific cultural, political, and social contexts as the book was composed. The Islamic Holy Book itself—perhaps the only constant across myriad manifestations of Islam—exemplifies the evolution at the heart of its tradition.

The Shahada also exemplifies the Islamic capacity for change. At first it simply had a “there is no god but God clause,” but later developed a more exclusive “Muhammad is His prophet” clause, and with the development of Shi’a theology a clause venerating Ali. Understanding the Shahada as a complex statement that changed over time and evolved differently depending on its sectarian context is a perfect microcosm for our ideal understanding of Islam: Islam is a complex tradition that has changed over time and evolved differently depending on its cultural context.

I also learned that Islam, and indeed religion in general, is neutral, rather than innately good or bad. Religion can be harmful in some limited contexts, it’s true, but in other contexts it can be a source of light, life, and social progress. The effect a religion has on the world has everything to do with the people who interpret its precepts and put it into practice. So, it is crucial to remember that despite the negative press the Islamic tradition receives because of a minority of fundamentalists who use Islam as an excuse to do violence and inflict pain, Islam is often a life-giving force that empowers human beings around the globe in numerous ways. Islam inspires art, provides the spark for social justice movements, and—as much of the literature in the AI54 syllabus taught me—has a capacity to focus on innate human dignity in the face of poverty and systems of oppression (the potential of religions to do both good and evil in the world is a core theme that informs the chaos that happens in the climax of my song “heavenly prototype”; more on that blog post later).

This course has also reminded me that religion and language have similar functions. That is, religious traditions provide a means of expressing both our humanity and our relationship with Divinity. To illustrate this, I recall my experience watching the Islamic film The Color of Paradise: paradoxically, the film is both totally familiar and completely alien to me. The emotional truths related by it—the pain of loss, the anguish of failure, the pangs of regret—are of course not limited to the Muslim experience and speak to all our lives. But the language that the film uses to articulate these truths is less familiar to me. First and foremost, the film is in Persian, a language of which I have zero knowledge. But even beyond that, the film speaks a religious language in which I have only a neophyte’s training. Its imagery and highly symbolic narrative employ Sufi paradigms that I do not fully understand, and the distinctly Islamic culture in which the film’s characters live and move and breathe is different from my own Christian culture. Religion provides a language for expressing truth, and because I didn’t speak the religious language of The Color of Paradise, I had to work hard to understand its message and get at the emotional and spiritual truths it elucidated. Thankfully, this course gave me the tools necessary to successfully analyze the film, so I did eventually figure it out, and when I did I was struck by how personal the message was. This exemplifies the general effect of my work in this course: beginning to engage with the language of the diverse Islamic tradition has equipped me to better understand the way Muslims around the world engage with questions that all humans know and wrestle with: questions of meaning, duty, spirit, soul, God, and love, and allows me to relate to my human brothers and sisters more deeply, regardless of religious affiliation.

In general terms, these were my biggest takeaways from AI54: For the Love of God and His Prophet. I hope these lessons I have learned over the course of the term shine through the blogposts I have created and curated over the past three months. I hope that you will get a taste of the vast, diverse, dynamic Islamic tradition through these posts, and I hope you will encounter Islamic language or styles with which you were previously unfamiliar.

Perhaps you, like me, have not given the Islamic tradition as much sophisticated thought as it deserves, and perhaps you, like me, will find that some of your constructions, definitions, and understandings surrounding Islam are incomplete. But this is not meant to be a threat. If you find your notions of Islam are on some level subverted, I hope you will feel the joy of growth and discovery that I have felt thanks to this course’s material. I also hope you will feel a sense of excitement at the prospect of a search for Divinity and meaning in life. As you will see as I go through some course themes and theology in relation to my posts, a lot of my work focuses on the mystical search for God. The art of the Islamic tradition evokes a sense of deep longing for Allah and fills me with wonder and anticipation. How exciting to embark on a spiritual quest! God willing, some of the excitement I have felt while engaging with the Islamic language of longing and searching for God will pass on to you in my posts.

My blog has seven pieces (not counting this introductory essay), and these pieces can be divided into two groups.The first group (posts 1-4) is a mini-album of original music that I composed, arranged, recorded, and mastered. The first song on the album is called “basmala,” the second “isa and the dead dog,” the third “love on moth’s wings,” and the fourth “heavenly prototype.” The third song is the title track. The second group (posts 5-7) consists of more eclectic media. Post #5 is a ghazal in English, post #6 is an epistolary short story, and post #7 is a poster/drawing that takes themes from an Iranian pro-Khomeini poster and subverts them for a different Islamic purpose.

The posts are all fairly different, but I think they are united in a few ways reflective of some core themes from the course. First and foremost, they are united in that they all speak to my favorite theological framework from AI54: Islam as a theology of love. They are also united in that they represent a collision between my own devout Christian identity and the Islamic identities and modes of expression I have studied this term. This collision, however, has been more constructive than destructive, because AI54 has so heavily focused on the aspects of the Islamic tradition that are pluralistic and inclusive.

I will begin by discussing the Islamic theology of Love that permeates my artwork and springs from various aspects of AI54. This theology of Love manifests in my blog in two ways.

The first is the theme of the soul’s mystical longing for God. As I have already stated, this theme has proven to be an integral part of Islam as presented in this course, and it shows up again and again. There is the mystical longing for God that informs the individual, quotidian prayer of Muslims around the world. There is the longing for God that inspires great works of art in the Sufi tradition. There is also the longing for God that is reflected in the desire of an imperfect world to reach the perfection of divinity. Many communities press for social justice and reform as a means of fulfilling this longing. Other, more fundamental communities try to fulfill this longing by fighting progress and attempting to return to an idealized ritual/cultural purity that they believe God wants for us. All in all, if we engage with the vast world of Islam, chances are we will encounter the longing of imperfect people for a perfect God, and this fact permeated both AI54 and the artwork in my blog.

Post #2, “isa and the dead dog,” reflects a mystical longing for God by expressing the distance between myself and the God I desire. This distance is highlighted by my own inability to see myself and the world with as much love and grace as God does, and this informs the lyrics (isa, it’s been lying there for far too long! / how do you see the beauty when the breath is gone?). Post #5, “a ghazal for the desert of the soul,” expresses long for and the discovery of God in unexpected places and in surprising ways, seeking God in desolation, silence, and the nothingness of contemplation. Post #7, called “an image of victory,” reflects longing for God by subverting Iranian pro-Khomeini symbolism and instead portraying an ultimate Muslim goal: union with God and His radical love through submission to His will (see the figure prostrating in the fire of God’s love). Post #3, my song “Love on Moth’s Wings,” perhaps most directly engages with the theme of longing for God by evoking the language of a South Asian ginan, a hymn about longing for and recklessly sacrificing oneself for a mystical beloved.

In addition to longing for God our Beloved, another component of the Islamic theology of love which inspires my blog posts is the collision of eternity with temporality: that is, the manifestation of Divinity in the fleeting world around us. One of my favorite quotes from the entire course is a quote from the Persian poet Saadi, who writes something to the effect of: “Every leaf of the tree becomes a page of sacred scripture, once the heart is opened and it has learnt to read” (I have heard this translated in a few ways). Saadi suggests that the beautiful world around us in all its complexity can be a source of revelation, not just the holy books we read and venerate. This notion about God’s presence in the natural world pervades much of the artwork we have engaged with in class, and by extension informs my own. The great Persian masnawi The Conference of the Birds uses language of nature and her creatures to tell a story about human relationship with God, imbuing birdsong with spiritual weight. In the tradition of that poem, my sixth post, “A Letter from a Sparrow,” tells the story of a shameful bird left behind. Here also do we find an articulation of human experience and religious truth in an interpretation of nature and nature’s denizens. The Islamic tradition of ghazal poetry often employs language of nature in spring time to express and exemplify the new life God gives; my ghazal (post #5) also uses imagery from the natural world to articulate a mystical experience, albeit in a somewhat subversive way (deserts and wastelands, rather than the beautiful, verdant gardens of traditional ghazals). Post #1, my song “basmala,” employs a chorus of many voices to remind us of how we can find God’s loving, compassionate voice in so many places, in nature and in our fellow human beings. Post #2 reflects how a pervasive God can be found even in the ugly aspects of nature, like dead animals. Post #4, my song “heavenly prototype,” is fundamentally about how we find God in the world. How does God manifest? Through incarnation? Through inlibration? Or perhaps simply the beauty of the creation which surrounds us? (the sun shines, the stars blink, / the tome talks in celestial ink…. You still come to us in love, / in book, or man, or leaf, or in anything i could dream of.)

This theology of love flows naturally into the collision of my Christian identity with the Islamic themes in the course. Professor Asani has endeavored to show us an Islam that is more inclusive, an Islam that transcends stricter political or religious ideologies. I remember learning that in Islamic thought, Jesus is understood as a devout Muslim in that he submits to God. Learning that made me wonder, I try to submit to the will of the one God. Within the bounds of the inclusive, Qur’anic sense of the word, am I perhaps a muslim, like Jesus? And if the line is blurred, what life-giving connections might exist between my Christian identity and modern Muslim identity? This search for connection between traditions informs my art. The song “basmala” has lyrics that are distinctly Muslim, and yet I can pray them very earnestly as a Christian (in the same way that Muslims often describe the Lord’s Prayer as Islamic). “isa and the dead dog” springs from a Muslim folk tale about the central figure of the Christian tradition—Jesus is beloved in both, and I play with that by engaging with the Muslim Jesus narrative as a Christ-follower. “love on moth’s wings” imbues Islamic ginan imagery with some flavors of my native Christian mysticism, and the combination because the traditions have more similarities than differences—both are based in longing for God’s Love. The lyrics of “heavenly prototype” collide the Islamic idea of the “Mother of the Book” and the manifestation of that Divine Word on earth with the distinctly Christian theme of Incarnation. My ghazal evokes the aesthetic of a famous Jesuit poet, G.M. Hopkins, while nevertheless fitting the paradigm of the Sufi love poem. My letter from a sparrow is in the tradition of The Conference of the Birds, but also explores a spiritual obstacle that is deeply personal to my own experience as a Christian. There is nothing explicitly Christian about my seventh post per se, but even in my poster, the desire presented is unity with the fire of God’s Love. This desire for Love is Islamic, but it is Christian too. I remember when Professor Asani told us about a Sufi who held that anyone who doesn’t think the Qur’an is a book about Love misunderstands the Qur’an. A lovely sentiment, made all the more beautiful by the fact that in the Christian canon Augustine of Hippo is known to have said the exact same thing about the Bible. The course theme of Islam as fundamentally inclusive allowed for my Christianity to interact with the Islamic tradition in fruitful ways through my artistic expression.

Ultimately, all of it is about Love. The simple lyrics of “basmala” reflect the core traits of a merciful and compassionate God, a God who is Love. “isa and the dead dog” shows how someone with high god-consciousness like Jesus can see beauty in ugliness because of divine Love. “love on moth’s wings” shows how we can give of ourselves in sacrifice to our beloved God out of mutual Love. “heavenly prototype” expounds on the myriad ways God makes himself known to us through creation, despite our continual failure to understand Him, out of Love. My ghazal suggest that even in silence and desolation, God meets us and fills us with His presence in an act of Love. My letter from a sparrow shows that despite our shame and sinfulness God calls us to submission and offers enlightenment out of Love. And, as shown in my poster, our ultimate goal as submitters (muslims) is to embrace God’s power and be enveloped in His Love. It’s all Love, and if you take anything away from my AI54 blogposts, let it be that.

(To see as PDF, click here!)

Post #7: An Image of Victory

April 25th, 2018

Hahaha! I feel a little insecure about this last blog post, I must confess. While I have record music for years, and written poetry and fiction for a while as well, I am very inexperienced in the world of visual art, and I have the skills of a five year old. So, I hope you will forgive the lack of technical skill in comparison with my other projects and appreciate nonetheless the intention and symbolism of my design.

This last piece is inspired by some of the scholarship from Shiva Balaghi and Lynn Gumpert that we explored in our readings. I am intrigued and mesmerized that the Iranian revolution hijacked and evolved certain symbols that are mainstays of the Shiite tradition. We see this exemplified dramatically in the political posters of the revolution that deposed the Shah and established Khomeini. Balaghi and Gumpert note how the traditional pardeh form which retells the tragic story of Karbala is augmented to recount the victory of the Ayatollah and the burgeoning Islamic republic. To assert the parallel between the victorious rebellion and Hussein’s defeat at Karbala is an interesting choice. As Professor Asani has pointed out, Shiite theology developed in a context of political defeat, not political victory, and Karbala is a core aspect of that understanding. While the political posters we examined are meant to convey a sense of celebration and victory, what is the real desired victory? What is the ultimate goal, that might transcend the establishment of any one part or sect in a hegemony or a political system?

The goal, I think is submission. It is oneness between God and God’s children, humanity. Surely this is lost in the eyes of people who cling to or vie for power, and forgotten by people who glorify, delight in, or celebrate violence. The real victory would be peace, and the real victor would not be the Shah or the Ayatollah or any human, but God, the Supreme.

With that in mind, I want to use the format of one of the posters discussed by Balaghi and Gumpert, and change it to fit a more cosmic sense of divine (rather than human) victory (see Fig. 61 for the original).

The flags of nationalism are replaced with the fire of God’s consuming love. The dominant face of Khomeini is replaced by the shadow of the submitting human, who—like Muhammad in that central Asian Night Journey manuscript we examined—basks, prostrates, and supplicates in that radiant and loving glory. Instead of a bleeding revolutionary holding a flag that says, “Independence, Freedom, and the Islamic Republic,” I have chosen to put an innocent child with a flag that simply says, “Love” (it’s also green, for the Prophet!) For Islam—at least, according to Rumi’s teacher—is about love, after all. And finally, instead of a band of revolutionaries, we see broken weapons, indicating an end to gratuitous human conflict. My goal was to take the pro-Khomeini image of victory and turn it into an image of God’s victory through the salvation of the human family. Also, I can’t figure out how to rotate it, my apologies!

Post #6: Letter from a Sparrow (an Epistolary Short Story)

April 25th, 2018

The Conference of the Birds was one of my favorite works of art that we discussed, both in lecture and in section. When I read it, I focused primarily on the presentations of the various birds at the beginning of the poem, and particularly on their respective vices. Attar did a wonderful job using the birds in the masnawi to show us the many ways we construct idols. These idols deter us from experiencing the fulness of mystical union, and are a stumbling block to the most complete islam.

A side note: the Hoopoe actually reminds very much of Jesus in the Gospels. Both he and Christ are adept at calling people out for making excuses and clinging to non-God, idolatrous attachments.

One particular exchange from The Conference of the Birds really spoke to me: The Finch’s Excuse. The “timid finch” is my favorite of the birds, and possibly has the most unique vice out of the bunch. Her idol is not something concrete and material–it’s not treasure, or lustful encounters, or purity–rather, her idol seems to be what the Hoopoe calls “humble ostentation.” The vibe I get is that the finch disingenuously plays up her own lowliness in an act not dissimilar to self-righteousness. And the Hoopoe will have none of it. But the Finch has a line that I relate to. She laments of the Simorgh: “I do not deserve to see His face.” And this line reminded me of a vice that I think is underrepresented at the beginning of the poem, but is nonetheless deeply important: shame. (Quotes from page 60 of the poem)

Shame has been a constant obstacle–or even idol–in my own spiritual life. I often think I don’t deserve the love of God because I am so ashamed of the mistakes I have made, ashamed of my lack of worthiness or perfection. The paradox is that intellectually, I understand how fallacious this is. God the Merciful and Compassionate invites me to bring my full self to divinity, to seek love and forgiveness despite my imperfection. But, my shame blocks me. I cling to it, in a way–the same way a rich man clings to gold–and it stops me from living out my quest for closeness with God.

What if I were also a bird? An ashamed bird? What if I had been summoned to the conference, and had hidden away because of the shame and self-loathing I felt? Here is a brief epistolary short story exploring this idea. It is written from the perspective of a sparrow whose vice is shame and self-loathing. The sparrow’s tragedy is that even though he has been invited both by God and by the Hoopoe to go on a journey, he is too scared to embark. His shame holds him back from the divine love that beckons him. The sparrow’s excuse is his belief that he is loathsome, unworthy, and unloved. This is perhaps the most false and dangerous spiritual lie of all.

Letter from a Sparrow

To my feathered brethren of the air and sea,

Oh, how I flew!

When the wind crash woke the wildwood, and the fanfare of ol’ Hoopoe broke forth in trumpeting triumph, I shook in my nest at the thought of that regal angel of a bird, that messenger who bore divine things—secrets, sweet nothings for lovers and the longing—and twigs tumbled from my makeshift home to the forest floor below.

I was summoned, like you. I was called to this conference and meeting, I who am a bird like all of you. But I was too frightened… after all, we were to look for the King of our kind, the Lord of All Lords, the Light-wearer and the Laugh-giver, and such a quest is enough to send me reeling into madness. How can I hope to see the face of God and not be sent to pieces? The wrath of that thing—that magnificent Other—is surely too much for tiny me to handle. Several of you have assured me that the thing we search for is a radical love, but I care not for such empty rhetoric. What love can overlook the weight of my shame in sin? What king can pardon the lowly sparrow-serf?

None can, or at least none should. How can I deserve enlightenment when I have spent my whole life both deliberately and accidentally bringing little bits of darkness into the world around me? Ever since I was but I chick I stole bread from my brothers in the nest, and then as soon as I could fly I took and took and took more and more—from the hands of infants I wrenched crumbs, from plates of kings I swiped sprigs and spice-pieces. Every greedy instance of flippant thievery echoes in my memory now. The humans say the sparrow sings for joy but if they, like Solomon, could discern my recent cries they would hear a lament at my own hubris. How I hate myself for the gluttonous hunger of my past; how such self-loathing compounds when I hate myself for that very same hate! Now I spend my days flitting violently from tree to tree and from leaf to leaf, abiding in the abysmal awareness of my failures as a creature of God. He created me, and what did I do? I failed. I am no steward of the earth, no vicegerent to this temporal world. I am no submitter. I have acted always with the taint of forgetfulness, with the scar of greed. I am so ashamed.

So, yes. When we convened to discuss a divine search how I flew! Far and away! I would have no part in the quest for the Lord of Lords, for I am less deserving than his lowliest peasant. I flew and I hid among the dead leaves and the mushrooms and the turkey-tails and the creatures that can’t fly. Under a log I dove, sobbing for the shame of sin.

Some of you sing relentlessly of mercy. Divine mercy. Compassionate mercy. Do not misunderstand me; I believe that such mercy exists. But that does not mean I believe it should be wasted on a sinful sparrow like me.

I must confess, there are moments when my self-loathing and shame do not reach these depths. Sometimes, especially after the vernal rains, I find myself flitting from tree to tree, from leaf to leaf, and a voice rings out in my head and heart. It ruffles my russet feathers and sets my beak chattering. How can such a song be both fearful and cheerful, both immanent and transcendent? I know not—sparrows are not meant to understand the secret seams of the universe, after all—but I have indeed heard the voice in all its contradictions.

“Will you stop badger-burrowing into your nest of shame, little one?” it says. And then, for that brief moment, all the leaves around me become like pages of the tomes humans read. The veins curl into arabesque lettering, the light-refracting droplets illuminating a latent message: “I love you,” the book of tree leaves says to me in silence. The affirmation fills up the void left by that still and small voice: fearful and cheerful, immanent and transcendent. Yes, for moments like that, the burden of my shame is transformed into levity. But the joy is ephemeral, and the call subtle—so subtle that it’s very easy to doubt it was uttered at all. And so, time and time again, I hear it and my heart lifts and then falls back down. And time and time again I run back to my hiding place of shame.

It is perhaps odd for me to hold these thoughts in my head all at once: the present shame that drives my tears and sad birdsong in the morning and night, and the intellectual memory of those joyful moments when a call of love picked me up out of my sorrow and beckoned me to go on a search for God. I do not know why I have not yet taken the plunge and joined you on your search, my brethren. I am so scared; had I the strength of Brother Hawk, then I might be able to shake the dust of my shame and rise in glorious flight to meet God. But I am no raptor, just a mere song bird who flits from tree to tree and from leaf to leaf. I am scared to bring my full self to our Lord… even if our Lord has from time to time brought His full self to me.

post #5: a ghazal for the desert of the soul

April 25th, 2018

a ghazal for the desert of the soul

love made man: molded as the weary earth,

imbued her with all wildlands of the earth.

spend life! reach longingly in sky-t’ward twist,

crawling up the mist; fly, blooms! from the earth,

your winking flowers, folded, forged for you,

bursting forth: innermost-light to the earth,

but then falling, wilted (dead in heartbeats);

grown stilted, godlife less glowed to the earth,

yea, love made man: formed as the flower’s birth,

but then abandoned? desert-turned the earth!

no. not left here sandy and desolate,

just with love for bleak nothings of the earth:

(a conversion: new eyes, new blooms, opened!)

for grey rocks, sky-nights, wastelands on the earth.

filled emptiness—love out of flower’s death—

emerges in your sojourn on the earth,

realized longing in the soul’s darkness:

luke’s loved in desolation of the earth.

Reflection

I figured that one of my pieces would take the form of a poem, but I assumed it would be a masnawi, or just a free verse response to another course theme. I’m surprised I ended up choosing the ghazal. The form is beautiful, but also very difficult (at least, so it seems to me). The continual repetition of the last phrase in each couplet, plus the radif, ensured I would always be limited on some level, and if I wasn’t careful, it could easily sound kitschy or sing-song. An interesting poetic challenge to undertake—and (haha) I’m not sure if I fully succeeded.

For my ghazal (which I have entitled a ghazal for the desert of the soul), I decided on a simple metrical rule of ten syllables per line. Thematically, I wanted it to be a divine love poem as is traditional for the ghazal, though in terms of imagery I think I diverged from convention somewhat.

My continual devotional obsession is with apophatic thought and apophatic prayer. In my native Christianity, I have heard apophatic prayer called the prayer of the desert. This is because to enter apophatic prayer is to enter a spiritual realm without much imagery, and without much color. It is a wasteland where there is you, there is God, and there isn’t meant to be much else.

I note in the work of J.T.P. de Brujin that in the expression of radical divine love, ghazals often feature imagery that reverts or subverts the values of traditional piety: drunkenness as the ideal state, the drunk as the divine lover, the Zoroastrian mage as the spiritual adept, et cetera (76). I love how somewhat unexpected images are utilized to convey the beauty of mystical experience. I also note that “to the ghazal poet, Nature in particular is full of analogies to his experiences of love” (de Brujin 63).

I decided to keep both of these characteristics in mind when composing a poem about apophatic union with God. The imagery of nature is central to my poem (my radif/rhyme combination is “the earth”), but I have tried to use nature in a subversive way. Here, God is not found in the vernal bloom of garden life that occurs in spring. In this poem, God is not found in green things. Rather, God is found in the silence of the desert, and in its death (which is akin to our death of the ego). Thus in my ghazal, I pay homage to both the presence of nature in the Sufi imagination, and also to the use of unexpected, subversive imagery for God.

A brief note on aesthetics: A personal favorite poet, G.M. Hopkins, also wrote a lot about nature and God. Grammatically, his verse is bizarre and, for lack of a better term, elegantly jagged. I tried to emulate this aesthetic in my ghazal.

Post #4: Heavenly Prototype

March 20th, 2018

The fourth, final, and most dramatic track of my mini-album, “heavenly prototype,” can be heard at this link:

https://oakwool.bandcamp.com/track/heavenly-prototype

I am particularly excited about how this song turned out. It is just short of 9 minutes long, and is fairly packed with numerous thematic elements. I’ll do my best to break it down as concisely as possible.

First and foremost, “heavenly prototype” ultimately engages with one question: How do we, the humans who are so inclined to forget God and God’s word, interact with and understand that word in our lives of faith(s)? The central image, from which the song gets its name, is the Umm al-Kitab, the “Mother of the Book,” otherwise known as the “heavenly prototype from which all scriptures come” (a quote from my lecture notes). This book is referred to in the song as “the heavenly prototype,” “our mother book,” and “the book above.” The first lyrical section of the song is concerned with Creation, and I connect the idea of this eternal, ever-writing book to what Nasr calls “the Primordial Word,” the original word that began the process of creation, and the “Divine Pen” (al-Qalam) which writes “the realities of all things” (Nasr 17). The Divine Pen is present (referenced as simply “The Pen”) throughout the song, and continues to write constantly in the language of God’s love.

How does that heavenly word get to us? I touch upon this in the song also. Way back at the beginning of the course, we discussed “Incarnation” and “Inlibration” (Word Made Flesh, Word Made Book, Lecture on January 30), and how the Word in Christianity is manifest in Jesus, whereas the Word in Islam is manifest in the Qur’an (which, as Sells points out on page 4 of Approaching the Qur’an, is why the parallel is not as strong between Jesus and Muhammad as it is between Jesus and the Recitation itself). The Word becomes manifest for Christian in Jesus (who “walks,” as I say in the song, with reference to Jesus’ adventurous traveling mystery), whereas the Word in Islam is manifest in the recited Qur’an (as I sing, “and Muhammad talks,” in reference to recitation, and also as a nod to Lupe Fiasco’s song about the Prophets). These are some ways that the Word, ancient and divine, gets to us, the young and God-forgetting humans. I make sure to mention both Jesus and the Qur’an as a way of remembering how the Heavenly Prototype is supposed to inform the scriptures of all the People of the Book, not just the Qur’an.

But what we do with the Word when we receive it through some kind of manifestation is not always as holy as the Word itself. This is the musing of the chaotic climax of the song, in which I lament that while the Word is a Word of love, it comes to us through different religious traditions (whether incarnated or inlibrated) and is twisted by some of us. It can be forged into a weapon, or a tool of oppression. As myriad interpretations of the Word arise in diverse religious traditions and sub-traditions, conflict is created. We disagree about the Word, we interpret it differently in different communities–this is exemplified by the chaotic instrumental that builds up halfway through the song. While the chaos is sometimes indicative of actual bloody or bigoted conflict, I think it also can simply reflect the sheer extent of the multiplicity of interpretations, on a scale which is difficult to wrap one’s mind around (generally, I’m influenced by the course’s cultural-studies approach when thinking about this. Different Islams, different Christianities, etc. all cry out in different ways during the chaotic sonic climax that makes any clarity or continuity harder to discern).

However, it ends on a peaceful, hopeful note, with quiet ambient instrumental and a meditation on how the divine Word itself, written by that Divine Pen, is so much more enduring than the petty hermeneutical conflicts we perpetuate with each other; God has the final Word, and thankfully, Creation can never be completely separate from it (Every leaf is a page of sacred scripture, to reference a Saadi line we discussed in class). Therefore, the trajectory of the song is meant to reflect the trajectory of the Word and the Heavenly Prototype as it is presented. It begins in peaceful ambience with the blissful institution of Creation by God, and then follows the Word as it is given as a gift through different scriptures and traditions to mankind, and then bastardized or confused by competing communities of interpretation, reaching an almost jarring sonic climax, before ending again in the peace of Divinity, the peace which the true Word always had since Creation began, the peace that defines the Heavenly Prototype even as all earthly scriptures face problems of interpretation. There is therefore ultimately a hope in God and God’s Love present at the end of the song, and I think it’s a fitting way to end the mini-album.

I really hope you enjoy these music pieces as much as I enjoyed composing and recording them!

Post #3: Love on Moth’s Wings

March 20th, 2018

The third and title-track of my mini-album is called “love on moth’s wings,” and can be heard at this link:

https://oakwool.bandcamp.com/album/love-on-moths-wings

(As with previous posts, the lyrics are found in the link).

In Week 7 of AI54, we examined various local kinds of devotional music. One example of this was a Ginan entitled “Hu(n) Re Peeaassee.” A ginan is a devotional hymn sung by members of Ismaili Shi’a communities in South Asia. When Professor Asani played a recording of an arrangement of “Hu(n) Ew Peeaassee” in class and showed us a translation of the lyrics, I could not believe how much I was moved by the words. I have long been in love with the mystical aspects of my native Anglo-Catholic Christianity, and to encounter mystical language from a different tradition that, while employing different vocabulary, nevertheless express the longing for unity with Divinity that I feel very strongly was a wonderful experience.

I greatly appreciated the lyrics of “Hu(n) Re Peeaassee,” and wanted to interact with them somehow by creating devotional/mystical music of my own. The result is this song, “love on moth’s wings,” a folk-inflected dream-pop ballad about the surrender of the self and the longing for the truest knowledge of God: Unity through Love. The lyrics of “love on moth’s wings” are perhaps best described as an augmented paraphrase. The verses borrow language directly from the Ginan, and the first line (“I thirst, O Beloved, for a vision of You) is a direct quote from the translation. As Asani points out in Chapter 3 of Ecstasy and Enlightenment, a central facet of this South Asian Ismaili music is the imagery of “spiritual marriage” and the language of the woman-soul (Asani 55-57), and I did my best to preserve this throughout my piece, particularly in the moments when I meditate on humility and self-sacrifice (as the Ginan says, “it is by becoming nothing that one is called a handmaiden”).

I note that in Ginans, just as a general mystical experience is often described, so also is a relationship between the disciple of the Ismaili Imam (the murid) and the Imam himself (Asani 57). I concede that this is downplayed slightly in my own synthesis of the Ginan’s lyrics; considering the choruses I composed to supplement the verses, I think the song has turned out to be an expression of longing for oneness with Divinity more than longing for spiritual marriage to a human religious leader.

I really dug into the animal imagery found in my favorite stanzas of the ginan: the displaced fish, the greedy bee, and most importantly, the moth that gives of itself, diving toward the light in an act of sacrifice. These creatures pop up in the second verse of “love on moth’s wings,” and the moth becomes the enduring, ideal image which I long to emulate for the rest of the song, as I “tumble toward the light” in an act of self-giving sacrifice to attain unity with the Beloved. The last line of the song evokes some more of the romantic/marriage language, at least implicitly: “I want to be yours.”

The first chorus is a product and description of my own contemplative prayer practice, which seeks the silence of unknowing to find the Unity with the Beloved that the ginan describes. The second chorus, while embellishing on the moth imagery present in the ginan, also evokes imagery of my favorite poem by Rumi:

I connect this falling which produces wings to the moths who sacrifice themselves for the sake of the light and for unity with the beloved in the ginan (“these fluttering broken beings who in honest falling find true wings, and through the door, love”). I really hope you like this song!

Post #2: Isa and the Dead Dog

March 20th, 2018

The second song on my mini-album is called “isa and the dead dog,” and can be listened to at this link:

https://oakwool.bandcamp.com/track/isa-and-the-dead-dog

(Also, the links also include a transcript of the lyrics of the song, so you can follow along with my language as you listen to the music).

In week 3 of the course, specifically on February 8, we discussed the role of Prophets in the Islamic tradition. We learned about how Muhammad is himself one of many Prophets (though, according to some Muslims, he is the last one). Many of the venerated Prophets in Islam are spiritual heroes shared with pre-Islamic tradition: Jewish figures such as Ibrahim (Abraham) or Yusuf (Joseph) or Musa (Moses), or Christian figures like Yahya (John the Baptist) or, most importantly for this post, Isa (Jesus). Prophetic stories have been prevalent in Islam since the inception of the Qur’an itself. The Qur’an highlights the presence of prophets in numerous religious traditions (see Suras 3:8, 10:47, 35:24, 4:164, 10:94, and also the miraculous Qur’anic retelling of the story of Joseph found in Sura 12 for examples). As the tradition has developed, prophetic stories have become their own genre, and are wonderful pedagogical tools for demonstrating the ways in which the Prophets are imitable paragons of virtue and righteousness.

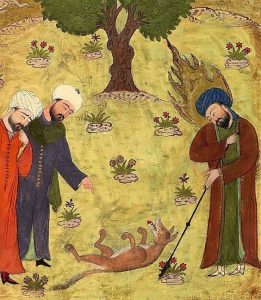

In week 3, my favorite example of a prophetic story that we learned was the story of Isa and the Dead Dog. As a devout Christian, it was great fun to see Jesus manifest in a refreshing way in another tradition! Professor Asani began his account by showing us this picture:

He told us the story: Isa was walking with his disciples when they came upon the corpse of a dog. The disciples ranted about how ugly and smelly the dead dog was, but Isa knelt down beside the dog and, ever seeing the divine beauty in all things, proclaimed that the dog had beautiful white teeth. What a lovely little parable!

For the second song of my mini-album, I attempted to retell (and also expand) the story of Isa and the Dead Dog. As it is a rather bizarre story, I tried my best to make the song a bit odd. The drum beat has a slight swing to it, and the piece features some synthesizer work that I think adds both beauty and idiosyncrasy (the story itself is both beautiful and idiosyncratic). The lyrics themselves add to the bizarre quality of the piece–I’m singing about Jesus and I’m singing about dog corpses, hardly a classic combo–but I think they’re a lot of fun! The first verse and chorus simply retell the story from the perspective of Isa’s disciples: they see a dead dog, and are astounded by Jesus’ ability to see beauty in the dead dog.

Then, I try to expand the parable and get at some possible ramifications for us, as people. What does it teach us about how God looks at humanity? What does it teach us about how each of us should view the world? With the second verse and last two choruses, I begin by asking the question, “Am I a dead dog?” (A metaphor, obviously). If I am a dead dog, then perhaps the Prophet Isa would still see the beauty in me, despite how very far I have fallen, despite how ugly the rest of the world thinks I am. Perhaps God feels the same way. Isa is a Prophetic paragon of virtue in this story because he imitates the Divine by seeing the inherent beauty and goodness of all created things, and as with all Prophets in the Muslim tradition, we would do well to learn from him.

Post #1: Basmala

March 20th, 2018

What a pleasure it has been to engage with all the materials of our course thus far! I am so excited to share that, for my first set of blog posts, I have produced a mini-album of original songs inspired by various aspects of the course material. The entire mini-album is called “love on moth’s wings” (for the record, I tend to avoid capital letters in my song titles and lyrics), and all four tracks can be found at this link:

https://oakwool.bandcamp.com/album/love-on-moths-wings

But, for ease of access, for each individual post, I’ll also include a link to the individual song about which I’m writing. The first song, and first post, is called “basmala,” and can be listened to here:

https://oakwool.bandcamp.com/track/basmala

“basmala” is an ambient folktronica song featuring a simple chord progression and one lyrical phrase, the Basmala (“bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīm,” a phrase which I have learned has myriad translations. I chose to work with one I heard in class and saw on the course website, “In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful), followed by an “Amen.” The Basmala reminds me of a prayer from my own tradition, the trinitarian formula (“in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit”) because of its versatility. Just as the trinitarian formula is used in all kinds of prayer circumstances in Christianity, both private and corporate, so too does the Basmala have variable uses. As I have seen in my examination of the Suras, almost every one begins with the Basmala (in the Michael Sells translation which we have examined for class readings, the translation is slightly different: “In the name of God the Compassionate the Caring”). Beyond Qur’anic use, we have seen how the Basmala permeates Muslim cultures. It is repeated prominently in daily prayers, featured prominently in Islamic calligraphy, and even manifests in the constitutions of many countries where Islam is the official religion. Nasr’s book, Islamic Art and Spirituality, which we read for class, begins with the Basmala.

I appreciate how the Basmala is made manifest in manifold contexts. This reflects that, for many Muslims, God consciousness is not only to be maintained in scripture itself or in corporate prayer. All endeavors may happen in the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful. This of course includes prayerful activities. As I recorded the other songs for my mini-album, I realized that I too was participating in an act of prayer, and so I wrote “basmala” to be the first track, to dedicate the whole album to the name of God and to reflect the prayerfulness of the art that I create. As Nasr writes, “Islamic art is the result of the manifestation of Unity upon the plane of multiplicity” (Nasr 7). Though I am not Muslim in the modern, ideological, categorical sense of the word, I do believe I am a lower-case “m” muslim in the Qur’anic sense of the word, in that I try my best to submit to the will of God (Asani, Infidel of Love, 28-29). Therefore, I hope that in some small way my art can contribute to the multiplicity of artistic manifestations of divine Unity, and so I begin it with the Basmala.

The last thing I’ll comment on is the structure and style of the song itself. It is supposed to evoke relaxed, peaceful feelings, setting a prayerful, reverent tone for the album (I wanted its sound to reflect the lyrical role this song plays, and so I went for an ethereal, heavenly, and mystical sonic quality, with soaring reverberations and ambient spaciousness). The listener will also notice that as the song continues, more instrumental layers build up and more voices are heard. This growing chorus of singers and instruments is intended to reflect how, while the song is an individual articulation of the Basmala, all things in Creation are ultimately expressions of Divinity–God communicates through Creation, and suffuses Creation with “divine signs” (Renard, Seven Doors to Islam, 2)–and so all things Created sing together: In the Name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful. Amen.