If the secret I had to keep had been mine, I must have confided it to Ada before we had been long together. But it was not mine, and I did not feel that I had a right to tell it, even to my guardian, unless some great emergency arose. It was a weight to bear alone; still my present duty appeared to be plain, and blest in the attachment of my dear, I did not want an impulse and encouragement to do it. Though often when she was asleep and all was quiet, the remembrance of my mother kept me waking and made the night sorrowful, I did not yield to it at another time; and Ada found me what I used to be—except, of course, in that particular of which I have said enough and which I have no intention of mentioning any more just now, if I can help it.

The difficulty that I felt in being quite composed that first evening when Ada asked me, over our work, if the family were at the house, and when I was obliged to answer yes, I believed so, for Lady Dedlock had spoken to me in the woods the day before yesterday, was great. Greater still when Ada asked me what she had said, and when I replied that she had been kind and interested, and when Ada, while admitting her beauty and elegance, remarked upon her proud manner and her imperious chilling air. But Charley helped me through, unconsciously, by telling us that Lady Dedlock had only stayed at the house two nights on her way from London to visit at some other great house in the next county and that she had left early on the morning after we had seen her at our view, as we called it. Charley verified the adage about little pitchers, I am sure, for she heard of more sayings and doings in a day than would have come to my ears in a month.

We were to stay a month at Mr. Boythorn’s. My pet had scarcely been there a bright week, as I recollect the time, when one evening after we had finished helping the gardener in watering his flowers, and just as the candles were lighted, Charley, appearing with a very important air behind Ada’s chair, beckoned me mysteriously out of the room.

“Oh! If you please, miss,” said Charley in a whisper, with her eyes at their roundest and largest. “You’re wanted at the Dedlock Arms.”

“Why, Charley,” said I, “who can possibly want me at the public-house?”

“I don’t know, miss,” returned Charley, putting her head forward and folding her hands tight upon the band of her little apron, which she always did in the enjoyment of anything mysterious or confidential, “but it’s a gentleman, miss, and his compliments, and will you please to come without saying anything about it.”

“Whose compliments, Charley?”

“His’n, miss,” returned Charley, whose grammatical education was advancing, but not very rapidly.

“And how do you come to be the messenger, Charley?”

“I am not the messenger, if you please, miss,” returned my little maid. “It was W. Grubble, miss.”

“And who is W. Grubble, Charley?”

“Mister Grubble, miss,” returned Charley. “Don’t you know, miss? The Dedlock Arms, by W. Grubble,” which Charley delivered as if she were slowly spelling out the sign.

“Aye? The landlord, Charley?”

“Yes, miss. If you please, miss, his wife is a beautiful woman, but she broke her ankle, and it never joined. And her brother’s the sawyer that was put in the cage, miss, and they expect he’ll drink himself to death entirely on beer,” said Charley.

Not knowing what might be the matter, and being easily apprehensive now, I thought it best to go to this place by myself. I bade Charley be quick with my bonnet and veil and my shawl, and having put them on, went away down the little hilly street, where I was as much at home as in Mr. Boythorn’s garden.

Mr. Grubble was standing in his shirt-sleeves at the door of his very clean little tavern waiting for me. He lifted off his hat with both hands when he saw me coming, and carrying it so, as if it were an iron vessel (it looked as heavy), preceded me along the sanded passage to his best parlour, a neat carpeted room with more plants in it than were quite convenient, a coloured print of Queen Caroline, several shells, a good many tea-trays, two stuffed and dried fish in glass cases, and either a curious egg or a curious pumpkin (but I don’t know which, and I doubt if many people did) hanging from his ceiling. I knew Mr. Grubble very well by sight, from his often standing at his door. A pleasant-looking, stoutish, middle-aged man who never seemed to consider himself cozily dressed for his own fire-side without his hat and top-boots, but who never wore a coat except at church.

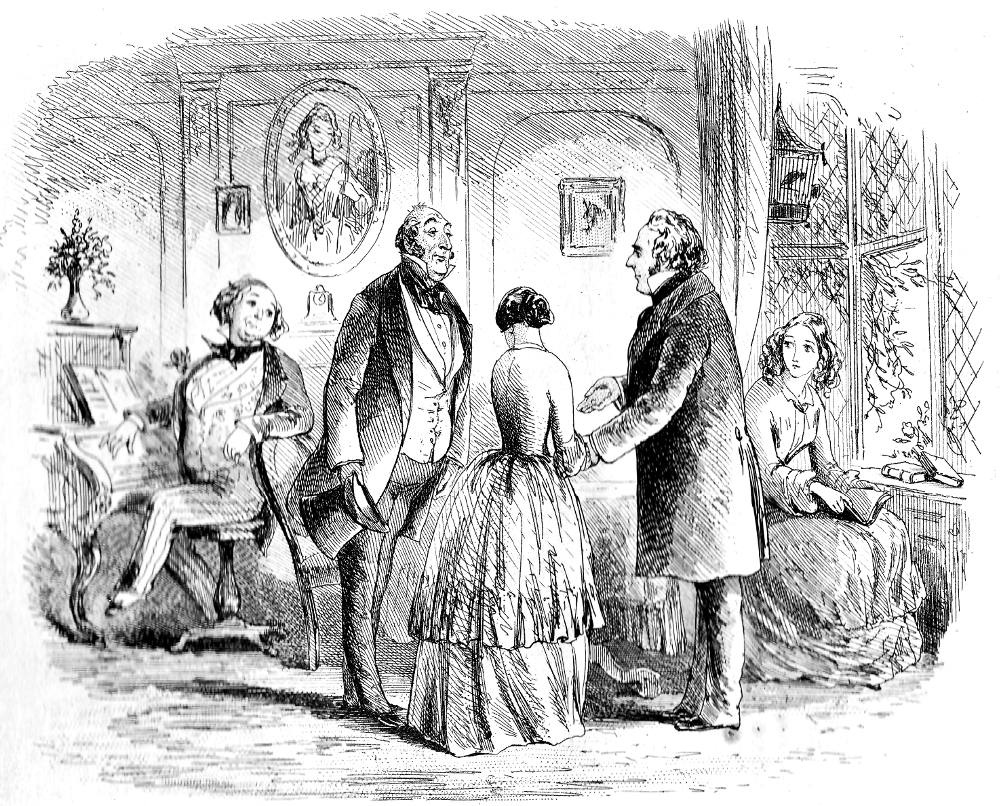

He snuffed the candle, and backing away a little to see how it looked, backed out of the room—unexpectedly to me, for I was going to ask him by whom he had been sent. The door of the opposite parlour being then opened, I heard some voices, familiar in my ears I thought, which stopped. A quick light step approached the room in which I was, and who should stand before me but Richard!

“My dear Esther!” he said. “My best friend!” And he really was so warm-hearted and earnest that in the first surprise and pleasure of his brotherly greeting I could scarcely find breath to tell him that Ada was well.

“Answering my very thoughts—always the same dear girl!” said Richard, leading me to a chair and seating himself beside me.

I put my veil up, but not quite.

“Always the same dear girl!” said Richard just as heartily as before.

I put up my veil altogether, and laying my hand on Richard’s sleeve and looking in his face, told him how much I thanked him for his kind welcome and how greatly I rejoiced to see him, the more so because of the determination I had made in my illness, which I now conveyed to him.

“My love,” said Richard, “there is no one with whom I have a greater wish to talk than you, for I want you to understand me.”

“And I want you, Richard,” said I, shaking my head, “to understand some one else.”

“Since you refer so immediately to John Jarndyce,” said Richard, “—I suppose you mean him?”

“Of course I do.”

“Then I may say at once that I am glad of it, because it is on that subject that I am anxious to be understood. By you, mind—you, my dear! I am not accountable to Mr. Jarndyce or Mr. Anybody.”

I was pained to find him taking this tone, and he observed it.

“Well, well, my dear,” said Richard, “we won’t go into that now. I want to appear quietly in your country-house here, with you under my arm, and give my charming cousin a surprise. I suppose your loyalty to John Jarndyce will allow that?”

“My dear Richard,” I returned, “you know you would be heartily welcome at his house—your home, if you will but consider it so; and you are as heartily welcome here!”

“Spoken like the best of little women!” cried Richard gaily.

I asked him how he liked his profession.

“Oh, I like it well enough!” said Richard. “It’s all right. It does as well as anything else, for a time. I don’t know that I shall care about it when I come to be settled, but I can sell out then and—however, never mind all that botheration at present.”

So young and handsome, and in all respects so perfectly the opposite of Miss Flite! And yet, in the clouded, eager, seeking look that passed over him, so dreadfully like her!

“I am in town on leave just now,” said Richard.

“Indeed?”

“Yes. I have run over to look after my—my Chancery interests before the long vacation,” said Richard, forcing a careless laugh. “We are beginning to spin along with that old suit at last, I promise you.”

No wonder that I shook my head!

“As you say, it’s not a pleasant subject.” Richard spoke with the same shade crossing his face as before. “Let it go to the four winds for to-night. Puff! Gone! Who do you suppose is with me?”

“Was it Mr. Skimpole’s voice I heard?”

“That’s the man! He does me more good than anybody. What a fascinating child it is!”

I asked Richard if any one knew of their coming down together. He answered, no, nobody. He had been to call upon the dear old infant—so he called Mr. Skimpole—and the dear old infant had told him where we were, and he had told the dear old infant he was bent on coming to see us, and the dear old infant had directly wanted to come too; and so he had brought him. “And he is worth—not to say his sordid expenses—but thrice his weight in gold,” said Richard. “He is such a cheery fellow. No worldliness about him. Fresh and green-hearted!”

I certainly did not see the proof of Mr. Skimpole’s worldliness in his having his expenses paid by Richard, but I made no remark about that. Indeed, he came in and turned our conversation. He was charmed to see me, said he had been shedding delicious tears of joy and sympathy at intervals for six weeks on my account, had never been so happy as in hearing of my progress, began to understand the mixture of good and evil in the world now, felt that he appreciated health the more when somebody else was ill, didn’t know but what it might be in the scheme of things that A should squint to make B happier in looking straight or that C should carry a wooden leg to make D better satisfied with his flesh and blood in a silk stocking.

“My dear Miss Summerson, here is our friend Richard,” said Mr. Skimpole, “full of the brightest visions of the future, which he evokes out of the darkness of Chancery. Now that’s delightful, that’s inspiriting, that’s full of poetry! In old times the woods and solitudes were made joyous to the shepherd by the imaginary piping and dancing of Pan and the nymphs. This present shepherd, our pastoral Richard, brightens the dull Inns of Court by making Fortune and her train sport through them to the melodious notes of a judgment from the bench. That’s very pleasant, you know! Some ill-conditioned growling fellow may say to me, ‘What’s the use of these legal and equitable abuses? How do you defend them?’ I reply, ‘My growling friend, I DON’T defend them, but they are very agreeable to me. There is a shepherd—youth, a friend of mine, who transmutes them into something highly fascinating to my simplicity. I don’t say it is for this that they exist—for I am a child among you worldly grumblers, and not called upon to account to you or myself for anything—but it may be so.'”

I began seriously to think that Richard could scarcely have found a worse friend than this. It made me uneasy that at such a time when he most required some right principle and purpose he should have this captivating looseness and putting-off of everything, this airy dispensing with all principle and purpose, at his elbow. I thought I could understand how such a nature as my guardian’s, experienced in the world and forced to contemplate the miserable evasions and contentions of the family misfortune, found an immense relief in Mr. Skimpole’s avowal of his weaknesses and display of guileless candour; but I could not satisfy myself that it was as artless as it seemed or that it did not serve Mr. Skimpole’s idle turn quite as well as any other part, and with less trouble.

They both walked back with me, and Mr. Skimpole leaving us at the gate, I walked softly in with Richard and said, “Ada, my love, I have brought a gentleman to visit you.” It was not difficult to read the blushing, startled face. She loved him dearly, and he knew it, and I knew it. It was a very transparent business, that meeting as cousins only.

I almost mistrusted myself as growing quite wicked in my suspicions, but I was not so sure that Richard loved her dearly. He admired her very much—any one must have done that—and I dare say would have renewed their youthful engagement with great pride and ardour but that he knew how she would respect her promise to my guardian. Still I had a tormenting idea that the influence upon him extended even here, that he was postponing his best truth and earnestness in this as in all things until Jarndyce and Jarndyce should be off his mind. Ah me! What Richard would have been without that blight, I never shall know now!

He told Ada, in his most ingenuous way, that he had not come to make any secret inroad on the terms she had accepted (rather too implicitly and confidingly, he thought) from Mr. Jarndyce, that he had come openly to see her and to see me and to justify himself for the present terms on which he stood with Mr. Jarndyce. As the dear old infant would be with us directly, he begged that I would make an appointment for the morning, when he might set himself right through the means of an unreserved conversation with me. I proposed to walk with him in the park at seven o’clock, and this was arranged. Mr. Skimpole soon afterwards appeared and made us merry for an hour. He particularly requested to see little Coavinses (meaning Charley) and told her, with a patriarchal air, that he had given her late father all the business in his power and that if one of her little brothers would make haste to get set up in the same profession, he hoped he should still be able to put a good deal of employment in his way.

“For I am constantly being taken in these nets,” said Mr. Skimpole, looking beamingly at us over a glass of wine-and-water, “and am constantly being bailed out—like a boat. Or paid off—like a ship’s company. Somebody always does it for me. I can’t do it, you know, for I never have any money. But somebody does it. I get out by somebody’s means; I am not like the starling; I get out. If you were to ask me who somebody is, upon my word I couldn’t tell you. Let us drink to somebody. God bless him!”

Richard was a little late in the morning, but I had not to wait for him long, and we turned into the park. The air was bright and dewy and the sky without a cloud. The birds sang delightfully; the sparkles in the fern, the grass, and trees, were exquisite to see; the richness of the woods seemed to have increased twenty-fold since yesterday, as if, in the still night when they had looked so massively hushed in sleep, Nature, through all the minute details of every wonderful leaf, had been more wakeful than usual for the glory of that day.

“This is a lovely place,” said Richard, looking round. “None of the jar and discord of law-suits here!”

But there was other trouble.

“I tell you what, my dear girl,” said Richard, “when I get affairs in general settled, I shall come down here, I think, and rest.”

“Would it not be better to rest now?” I asked.

“Oh, as to resting NOW,” said Richard, “or as to doing anything very definite NOW, that’s not easy. In short, it can’t be done; I can’t do it at least.”

“Why not?” said I.

“You know why not, Esther. If you were living in an unfinished house, liable to have the roof put on or taken off—to be from top to bottom pulled down or built up—to-morrow, next day, next week, next month, next year—you would find it hard to rest or settle. So do I. Now? There’s no now for us suitors.”

I could almost have believed in the attraction on which my poor little wandering friend had expatiated when I saw again the darkened look of last night. Terrible to think it had in it also a shade of that unfortunate man who had died.

“My dear Richard,” said I, “this is a bad beginning of our conversation.”

“I knew you would tell me so, Dame Durden.”

“And not I alone, dear Richard. It was not I who cautioned you once never to found a hope or expectation on the family curse.”

“There you come back to John Jarndyce!” said Richard impatiently. “Well! We must approach him sooner or later, for he is the staple of what I have to say, and it’s as well at once. My dear Esther, how can you be so blind? Don’t you see that he is an interested party and that it may be very well for him to wish me to know nothing of the suit, and care nothing about it, but that it may not be quite so well for me?”

“Oh, Richard,” I remonstrated, “is it possible that you can ever have seen him and heard him, that you can ever have lived under his roof and known him, and can yet breathe, even to me in this solitary place where there is no one to hear us, such unworthy suspicions?”

He reddened deeply, as if his natural generosity felt a pang of reproach. He was silent for a little while before he replied in a subdued voice, “Esther, I am sure you know that I am not a mean fellow and that I have some sense of suspicion and distrust being poor qualities in one of my years.”

“I know it very well,” said I. “I am not more sure of anything.”

“That’s a dear girl,” retorted Richard, “and like you, because it gives me comfort. I had need to get some scrap of comfort out of all this business, for it’s a bad one at the best, as I have no occasion to tell you.”

“I know perfectly,” said I. “I know as well, Richard—what shall I say? as well as you do—that such misconstructions are foreign to your nature. And I know, as well as you know, what so changes it.”

“Come, sister, come,” said Richard a little more gaily, “you will be fair with me at all events. If I have the misfortune to be under that influence, so has he. If it has a little twisted me, it may have a little twisted him too. I don’t say that he is not an honourable man, out of all this complication and uncertainty; I am sure he is. But it taints everybody. You know it taints everybody. You have heard him say so fifty times. Then why should HE escape?”

“Because,” said I, “his is an uncommon character, and he has resolutely kept himself outside the circle, Richard.”

“Oh, because and because!” replied Richard in his vivacious way. “I am not sure, my dear girl, but that it may be wise and specious to preserve that outward indifference. It may cause other parties interested to become lax about their interests; and people may die off, and points may drag themselves out of memory, and many things may smoothly happen that are convenient enough.”

I was so touched with pity for Richard that I could not reproach him any more, even by a look. I remembered my guardian’s gentleness towards his errors and with what perfect freedom from resentment he had spoken of them.

“Esther,” Richard resumed, “you are not to suppose that I have come here to make underhanded charges against John Jarndyce. I have only come to justify myself. What I say is, it was all very well and we got on very well while I was a boy, utterly regardless of this same suit; but as soon as I began to take an interest in it and to look into it, then it was quite another thing. Then John Jarndyce discovers that Ada and I must break off and that if I don’t amend that very objectionable course, I am not fit for her. Now, Esther, I don’t mean to amend that very objectionable course: I will not hold John Jarndyce’s favour on those unfair terms of compromise, which he has no right to dictate. Whether it pleases him or displeases him, I must maintain my rights and Ada’s. I have been thinking about it a good deal, and this is the conclusion I have come to.”

Poor dear Richard! He had indeed been thinking about it a good deal. His face, his voice, his manner, all showed that too plainly.

“So I tell him honourably (you are to know I have written to him about all this) that we are at issue and that we had better be at issue openly than covertly. I thank him for his goodwill and his protection, and he goes his road, and I go mine. The fact is, our roads are not the same. Under one of the wills in dispute, I should take much more than he. I don’t mean to say that it is the one to be established, but there it is, and it has its chance.”

“I have not to learn from you, my dear Richard,” said I, “of your letter. I had heard of it already without an offended or angry word.”

“Indeed?” replied Richard, softening. “I am glad I said he was an honourable man, out of all this wretched affair. But I always say that and have never doubted it. Now, my dear Esther, I know these views of mine appear extremely harsh to you, and will to Ada when you tell her what has passed between us. But if you had gone into the case as I have, if you had only applied yourself to the papers as I did when I was at Kenge’s, if you only knew what an accumulation of charges and counter-charges, and suspicions and cross-suspicions, they involve, you would think me moderate in comparison.”

“Perhaps so,” said I. “But do you think that, among those many papers, there is much truth and justice, Richard?”

“There is truth and justice somewhere in the case, Esther—”

“Or was once, long ago,” said I.

“Is—is—must be somewhere,” pursued Richard impetuously, “and must be brought out. To allow Ada to be made a bribe and hush-money of is not the way to bring it out. You say the suit is changing me; John Jarndyce says it changes, has changed, and will change everybody who has any share in it. Then the greater right I have on my side when I resolve to do all I can to bring it to an end.”

“All you can, Richard! Do you think that in these many years no others have done all they could? Has the difficulty grown easier because of so many failures?”

“It can’t last for ever,” returned Richard with a fierceness kindling in him which again presented to me that last sad reminder. “I am young and earnest, and energy and determination have done wonders many a time. Others have only half thrown themselves into it. I devote myself to it. I make it the object of my life.”

“Oh, Richard, my dear, so much the worse, so much the worse!”

“No, no, no, don’t you be afraid for me,” he returned affectionately. “You’re a dear, good, wise, quiet, blessed girl; but you have your prepossessions. So I come round to John Jarndyce. I tell you, my good Esther, when he and I were on those terms which he found so convenient, we were not on natural terms.”

“Are division and animosity your natural terms, Richard?”

“No, I don’t say that. I mean that all this business puts us on unnatural terms, with which natural relations are incompatible. See another reason for urging it on! I may find out when it’s over that I have been mistaken in John Jarndyce. My head may be clearer when I am free of it, and I may then agree with what you say to-day. Very well. Then I shall acknowledge it and make him reparation.”

Everything postponed to that imaginary time! Everything held in confusion and indecision until then!

“Now, my best of confidantes,” said Richard, “I want my cousin Ada to understand that I am not captious, fickle, and wilful about John Jarndyce, but that I have this purpose and reason at my back. I wish to represent myself to her through you, because she has a great esteem and respect for her cousin John; and I know you will soften the course I take, even though you disapprove of it; and—and in short,” said Richard, who had been hesitating through these words, “I—I don’t like to represent myself in this litigious, contentious, doubting character to a confiding girl like Ada.”

I told him that he was more like himself in those latter words than in anything he had said yet.

“Why,” acknowledged Richard, “that may be true enough, my love. I rather feel it to be so. But I shall be able to give myself fair-play by and by. I shall come all right again, then, don’t you be afraid.”

I asked him if this were all he wished me to tell Ada.

“Not quite,” said Richard. “I am bound not to withhold from her that John Jarndyce answered my letter in his usual manner, addressing me as ‘My dear Rick,’ trying to argue me out of my opinions, and telling me that they should make no difference in him. (All very well of course, but not altering the case.) I also want Ada to know that if I see her seldom just now, I am looking after her interests as well as my own—we two being in the same boat exactly—and that I hope she will not suppose from any flying rumours she may hear that I am at all light-headed or imprudent; on the contrary, I am always looking forward to the termination of the suit, and always planning in that direction. Being of age now and having taken the step I have taken, I consider myself free from any accountability to John Jarndyce; but Ada being still a ward of the court, I don’t yet ask her to renew our engagement. When she is free to act for herself, I shall be myself once more and we shall both be in very different worldly circumstances, I believe. If you tell her all this with the advantage of your considerate way, you will do me a very great and a very kind service, my dear Esther; and I shall knock Jarndyce and Jarndyce on the head with greater vigour. Of course I ask for no secrecy at Bleak House.”

“Richard,” said I, “you place great confidence in me, but I fear you will not take advice from me?”

“It’s impossible that I can on this subject, my dear girl. On any other, readily.”

As if there were any other in his life! As if his whole career and character were not being dyed one colour!

“But I may ask you a question, Richard?”

“I think so,” said he, laughing. “I don’t know who may not, if you may not.”

“You say, yourself, you are not leading a very settled life.”

“How can I, my dear Esther, with nothing settled!”

“Are you in debt again?”

“Why, of course I am,” said Richard, astonished at my simplicity.

“Is it of course?”

“My dear child, certainly. I can’t throw myself into an object so completely without expense. You forget, or perhaps you don’t know, that under either of the wills Ada and I take something. It’s only a question between the larger sum and the smaller. I shall be within the mark any way. Bless your heart, my excellent girl,” said Richard, quite amused with me, “I shall be all right! I shall pull through, my dear!”

I felt so deeply sensible of the danger in which he stood that I tried, in Ada’s name, in my guardian’s, in my own, by every fervent means that I could think of, to warn him of it and to show him some of his mistakes. He received everything I said with patience and gentleness, but it all rebounded from him without taking the least effect. I could not wonder at this after the reception his preoccupied mind had given to my guardian’s letter, but I determined to try Ada’s influence yet.

So when our walk brought us round to the village again, and I went home to breakfast, I prepared Ada for the account I was going to give her and told her exactly what reason we had to dread that Richard was losing himself and scattering his whole life to the winds. It made her very unhappy, of course, though she had a far, far greater reliance on his correcting his errors than I could have—which was so natural and loving in my dear!—and she presently wrote him this little letter:

My dearest cousin,

Esther has told me all you said to her this morning. I write this to repeat most earnestly for myself all that she said to you and to let you know how sure I am that you will sooner or later find our cousin John a pattern of truth, sincerity, and goodness, when you will deeply, deeply grieve to have done him (without intending it) so much wrong.

I do not quite know how to write what I wish to say next, but I trust you will understand it as I mean it. I have some fears, my dearest cousin, that it may be partly for my sake you are now laying up so much unhappiness for yourself—and if for yourself, for me. In case this should be so, or in case you should entertain much thought of me in what you are doing, I most earnestly entreat and beg you to desist. You can do nothing for my sake that will make me half so happy as for ever turning your back upon the shadow in which we both were born. Do not be angry with me for saying this. Pray, pray, dear Richard, for my sake, and for your own, and in a natural repugnance for that source of trouble which had its share in making us both orphans when we were very young, pray, pray, let it go for ever. We have reason to know by this time that there is no good in it and no hope, that there is nothing to be got from it but sorrow.

My dearest cousin, it is needless for me to say that you are quite free and that it is very likely you may find some one whom you will love much better than your first fancy. I am quite sure, if you will let me say so, that the object of your choice would greatly prefer to follow your fortunes far and wide, however moderate or poor, and see you happy, doing your duty and pursuing your chosen way, than to have the hope of being, or even to be, very rich with you (if such a thing were possible) at the cost of dragging years of procrastination and anxiety and of your indifference to other aims. You may wonder at my saying this so confidently with so little knowledge or experience, but I know it for a certainty from my own heart.

Ever, my dearest cousin, your most affectionate

Ada

This note brought Richard to us very soon, but it made little change in him if any. We would fairly try, he said, who was right and who was wrong—he would show us—we should see! He was animated and glowing, as if Ada’s tenderness had gratified him; but I could only hope, with a sigh, that the letter might have some stronger effect upon his mind on re-perusal than it assuredly had then.

As they were to remain with us that day and had taken their places to return by the coach next morning, I sought an opportunity of speaking to Mr. Skimpole. Our out-of-door life easily threw one in my way, and I delicately said that there was a responsibility in encouraging Richard.

“Responsibility, my dear Miss Summerson?” he repeated, catching at the word with the pleasantest smile. “I am the last man in the world for such a thing. I never was responsible in my life—I can’t be.”

“I am afraid everybody is obliged to be,” said I timidly enough, he being so much older and more clever than I.

“No, really?” said Mr. Skimpole, receiving this new light with a most agreeable jocularity of surprise. “But every man’s not obliged to be solvent? I am not. I never was. See, my dear Miss Summerson,” he took a handful of loose silver and halfpence from his pocket, “there’s so much money. I have not an idea how much. I have not the power of counting. Call it four and ninepence—call it four pound nine. They tell me I owe more than that. I dare say I do. I dare say I owe as much as good-natured people will let me owe. If they don’t stop, why should I? There you have Harold Skimpole in little. If that’s responsibility, I am responsible.”

The perfect ease of manner with which he put the money up again and looked at me with a smile on his refined face, as if he had been mentioning a curious little fact about somebody else, almost made me feel as if he really had nothing to do with it.

“Now, when you mention responsibility,” he resumed, “I am disposed to say that I never had the happiness of knowing any one whom I should consider so refreshingly responsible as yourself. You appear to me to be the very touchstone of responsibility. When I see you, my dear Miss Summerson, intent upon the perfect working of the whole little orderly system of which you are the centre, I feel inclined to say to myself—in fact I do say to myself very often—THAT’S responsibility!”

It was difficult, after this, to explain what I meant; but I persisted so far as to say that we all hoped he would check and not confirm Richard in the sanguine views he entertained just then.

“Most willingly,” he retorted, “if I could. But, my dear Miss Summerson, I have no art, no disguise. If he takes me by the hand and leads me through Westminster Hall in an airy procession after fortune, I must go. If he says, ‘Skimpole, join the dance!’ I must join it. Common sense wouldn’t, I know, but I have NO common sense.”

It was very unfortunate for Richard, I said.

“Do you think so!” returned Mr. Skimpole. “Don’t say that, don’t say that. Let us suppose him keeping company with Common Sense—an excellent man—a good deal wrinkled—dreadfully practical—change for a ten-pound note in every pocket—ruled account-book in his hand—say, upon the whole, resembling a tax-gatherer. Our dear Richard, sanguine, ardent, overleaping obstacles, bursting with poetry like a young bud, says to this highly respectable companion, ‘I see a golden prospect before me; it’s very bright, it’s very beautiful, it’s very joyous; here I go, bounding over the landscape to come at it!’ The respectable companion instantly knocks him down with the ruled account-book; tells him in a literal, prosaic way that he sees no such thing; shows him it’s nothing but fees, fraud, horsehair wigs, and black gowns. Now you know that’s a painful change—sensible in the last degree, I have no doubt, but disagreeable. I can’t do it. I haven’t got the ruled account-book, I have none of the tax-gathering elements in my composition, I am not at all respectable, and I don’t want to be. Odd perhaps, but so it is!”

It was idle to say more, so I proposed that we should join Ada and Richard, who were a little in advance, and I gave up Mr. Skimpole in despair. He had been over the Hall in the course of the morning and whimsically described the family pictures as we walked. There were such portentous shepherdesses among the Ladies Dedlock dead and gone, he told us, that peaceful crooks became weapons of assault in their hands. They tended their flocks severely in buckram and powder and put their sticking-plaster patches on to terrify commoners as the chiefs of some other tribes put on their war-paint. There was a Sir Somebody Dedlock, with a battle, a sprung-mine, volumes of smoke, flashes of lightning, a town on fire, and a stormed fort, all in full action between his horse’s two hind legs, showing, he supposed, how little a Dedlock made of such trifles. The whole race he represented as having evidently been, in life, what he called “stuffed people”—a large collection, glassy eyed, set up in the most approved manner on their various twigs and perches, very correct, perfectly free from animation, and always in glass cases.

I was not so easy now during any reference to the name but that I felt it a relief when Richard, with an exclamation of surprise, hurried away to meet a stranger whom he first descried coming slowly towards us.

“Dear me!” said Mr. Skimpole. “Vholes!”

We asked if that were a friend of Richard’s.

“Friend and legal adviser,” said Mr. Skimpole. “Now, my dear Miss Summerson, if you want common sense, responsibility, and respectability, all united—if you want an exemplary man—Vholes is THE man.”

We had not known, we said, that Richard was assisted by any gentleman of that name.

“When he emerged from legal infancy,” returned Mr. Skimpole, “he parted from our conversational friend Kenge and took up, I believe, with Vholes. Indeed, I know he did, because I introduced him to Vholes.”

“Had you known him long?” asked Ada.

“Vholes? My dear Miss Clare, I had had that kind of acquaintance with him which I have had with several gentlemen of his profession. He had done something or other in a very agreeable, civil manner—taken proceedings, I think, is the expression—which ended in the proceeding of his taking ME. Somebody was so good as to step in and pay the money—something and fourpence was the amount; I forget the pounds and shillings, but I know it ended with fourpence, because it struck me at the time as being so odd that I could owe anybody fourpence—and after that I brought them together. Vholes asked me for the introduction, and I gave it. Now I come to think of it,” he looked inquiringly at us with his frankest smile as he made the discovery, “Vholes bribed me, perhaps? He gave me something and called it commission. Was it a five-pound note? Do you know, I think it MUST have been a five-pound note!”

His further consideration of the point was prevented by Richard’s coming back to us in an excited state and hastily representing Mr. Vholes—a sallow man with pinched lips that looked as if they were cold, a red eruption here and there upon his face, tall and thin, about fifty years of age, high-shouldered, and stooping. Dressed in black, black-gloved, and buttoned to the chin, there was nothing so remarkable in him as a lifeless manner and a slow, fixed way he had of looking at Richard.

“I hope I don’t disturb you, ladies,” said Mr. Vholes, and now I observed that he was further remarkable for an inward manner of speaking. “I arranged with Mr. Carstone that he should always know when his cause was in the Chancellor’s paper, and being informed by one of my clerks last night after post time that it stood, rather unexpectedly, in the paper for to-morrow, I put myself into the coach early this morning and came down to confer with him.”

“Yes,” said Richard, flushed, and looking triumphantly at Ada and me, “we don’t do these things in the old slow way now. We spin along now! Mr. Vholes, we must hire something to get over to the post town in, and catch the mail to-night, and go up by it!”

“Anything you please, sir,” returned Mr. Vholes. “I am quite at your service.”

“Let me see,” said Richard, looking at his watch. “If I run down to the Dedlock, and get my portmanteau fastened up, and order a gig, or a chaise, or whatever’s to be got, we shall have an hour then before starting. I’ll come back to tea. Cousin Ada, will you and Esther take care of Mr. Vholes when I am gone?”

He was away directly, in his heat and hurry, and was soon lost in the dusk of evening. We who were left walked on towards the house.

“Is Mr. Carstone’s presence necessary to-morrow, Sir?” said I. “Can it do any good?”

“No, miss,” Mr. Vholes replied. “I am not aware that it can.”

Both Ada and I expressed our regret that he should go, then, only to be disappointed.

“Mr. Carstone has laid down the principle of watching his own interests,” said Mr. Vholes, “and when a client lays down his own principle, and it is not immoral, it devolves upon me to carry it out. I wish in business to be exact and open. I am a widower with three daughters—Emma, Jane, and Caroline—and my desire is so to discharge the duties of life as to leave them a good name. This appears to be a pleasant spot, miss.”

The remark being made to me in consequence of my being next him as we walked, I assented and enumerated its chief attractions.

“Indeed?” said Mr. Vholes. “I have the privilege of supporting an aged father in the Vale of Taunton—his native place—and I admire that country very much. I had no idea there was anything so attractive here.”

To keep up the conversation, I asked Mr. Vholes if he would like to live altogether in the country.

“There, miss,” said he, “you touch me on a tender string. My health is not good (my digestion being much impaired), and if I had only myself to consider, I should take refuge in rural habits, especially as the cares of business have prevented me from ever coming much into contact with general society, and particularly with ladies’ society, which I have most wished to mix in. But with my three daughters, Emma, Jane, and Caroline—and my aged father—I cannot afford to be selfish. It is true I have no longer to maintain a dear grandmother who died in her hundred and second year, but enough remains to render it indispensable that the mill should be always going.”

It required some attention to hear him on account of his inward speaking and his lifeless manner.

“You will excuse my having mentioned my daughters,” he said. “They are my weak point. I wish to leave the poor girls some little independence, as well as a good name.”

We now arrived at Mr. Boythorn’s house, where the tea-table, all prepared, was awaiting us. Richard came in restless and hurried shortly afterwards, and leaning over Mr. Vholes’s chair, whispered something in his ear. Mr. Vholes replied aloud—or as nearly aloud I suppose as he had ever replied to anything—”You will drive me, will you, sir? It is all the same to me, sir. Anything you please. I am quite at your service.”

We understood from what followed that Mr. Skimpole was to be left until the morning to occupy the two places which had been already paid for. As Ada and I were both in low spirits concerning Richard and very sorry so to part with him, we made it as plain as we politely could that we should leave Mr. Skimpole to the Dedlock Arms and retire when the night-travellers were gone.

Richard’s high spirits carrying everything before them, we all went out together to the top of the hill above the village, where he had ordered a gig to wait and where we found a man with a lantern standing at the head of the gaunt pale horse that had been harnessed to it.

I never shall forget those two seated side by side in the lantern’s light, Richard all flush and fire and laughter, with the reins in his hand; Mr. Vholes quite still, black-gloved, and buttoned up, looking at him as if he were looking at his prey and charming it. I have before me the whole picture of the warm dark night, the summer lightning, the dusty track of road closed in by hedgerows and high trees, the gaunt pale horse with his ears pricked up, and the driving away at speed to Jarndyce and Jarndyce.

My dear girl told me that night how Richard’s being thereafter prosperous or ruined, befriended or deserted, could only make this difference to her, that the more he needed love from one unchanging heart, the more love that unchanging heart would have to give him; how he thought of her through his present errors, and she would think of him at all times—never of herself if she could devote herself to him, never of her own delights if she could minister to his.

And she kept her word?

I look along the road before me, where the distance already shortens and the journey’s end is growing visible; and true and good above the dead sea of the Chancery suit and all the ashy fruit it cast ashore, I think I see my darling.

Librivox Recording: Chapter 37