Fracking Policy, Environmental Justice and Vulnerable communities

ø

Fracking Policy, Environmental Justice and

Vulnerable communities

Carol Blenda Ilievski

ABSTRACT

Like most industries in our country, fracking has good and imperfect points. Fracking is a technological breakthrough that has dramatically increased the energy supply to the entire economy and has led to substantial increases in U.S.A. domestic oil and gas production, thereby remarkably lessening the need for fossil fuel imports. In the latter, it has been linked with contaminated drinking water due to the chemicals injected in the process. The process itself increased the incidence of earthquakes, which is undoubtedly harmful. There is also some evidence that fracking would not exist, at least not to the present extent, were it not for the lack of policies regulating this industry, government subsidies, and misallocated resources. Despite the benefits of energy security for the nation, job creation, and economic gains, there are potential environmental and socio-economic risks to communities along the path of this industry associated with this unconventional extraction of oil and gas.

1. INTRODUCTION

Fracking nowadays has become a controversial industry around the world. While most European countries have banned this practice, the United States has economically benefited from fracking. In later years, researchers laid out scientific evidence linking fracking to adverse health outcomes. At the same time, policy experts examined the extent to which the public’s health is considered in the development and operation of fracking regulation and the impediments to further regulation on both the state and federal levels. In recent years, comprehensive research has shown that communities living near hydraulic fracturing wells and their surrounding infrastructure are at risk of multiple health problems. With the knowledge of fracking’s harmful effects comes the ethical question of who bears these risks and what legislation is doing to correct or create change for the affected communities.

The lack of federal policies and regulations has created a boom in the industry which has helped the U.S.A.’s oil dependency. Nevertheless, public health and environmental justice advocates speak about effective policy solutions and partnering with affected communities to correct this industry’s responsibilities and flaws. This briefing aims to propose federal laws and fracking regulations that Federal, State governments, EPA, and independent consulting companies should execute. Fracking policy proposals and regulations on this issue have been fueled by its exemption in the Safe Drinking Water Act. The development of this policy issue involves the introduction of proposals by several sponsors, committee discussions and reports, and floor debates in both houses of Congress. Nonetheless, policymakers have faced numerous difficulties and failed to date in enacting federal regulations on fracking. Furthermore, this paper looks to explores the leadership of Indigenous advocates, scientists, and policy experts addressing the impact of fracking on their nations and communities trying to suggest innovative legal and advocacy strategies and alternative solutions. This brief examines the ethical concerns created by the fracking industry and how they relate to the three main types of environmental justice for the communities affected by fracking.

2. WHAT IS FRACKING – POLICY ISSUES.

Fracking or hydraulic fracturing constitutes a significant issue plaguing America’s energy industry over the last two decades. It may be described as increasing natural gas and oil well production by opening or breaking rock formations through high-pressure fluid injections (Finkel, Hays & Law, 2013). The above extraction mode has garnered significant focus within America as it allows the extraction of gas and oil from shale rock. The process has elevated gas and oil yields in the nation, rendering it one of the world’s largest natural gas and oil producers. Hydraulic fracturing has received considerable attention in policy development. Thus, the United States federal government has embarked on several legislative and administrative initiatives relating to fracking operations for over two decades (Hill, 2021). This practice has been exempted from federal reach, leaving regulation to the states, which appear vulnerable to capture by economic and energy interests.

Likewise, litigation about fracking for coal-bed methane (CBM) gas was not regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). This act controls and regulates underground injection activities through its Underground Injection Control Program, which includes Class II wells linked to oil production and natural gas. While fracking is a national issue, it is currently exempted from national environmental laws and all requirements of the Safe Drinking Water Act (Cupas, 2008). Given this exemption, the regulation of hydraulic fracturing or fracking has primarily been made at the state level. However, the U.S. energy sector has generated a need for changes in the regulation of hydraulic fracturing. The needs surrounding fracking policy have, in turn, acted as the historical and political context for formulating federal regulations on this issue. Most federal laws put forward on fracking have yet to be ratified. Sponsored by several senators and House Representatives, appropriate committees have taken up these laws. These committees have been acquainted with and received referrals of recommended fracking-related resolutions, discussed before being forwarded to the entire chamber. Since the first introduction of the 2009 Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals Act, it has yet to be ratified despite being re-introduced four more times (Coton, 2017). Challenges to implementing these federal rules may be ascribed to state policy establishment and control over drilling undertakings (Spence, 2014). The Fracking policy history is plagued with controversy and constant delays. To better understand the negligence over the issue, a timeline is disclosed below.

2.1 FRACKING POLICY TIMELINE

- In 1950, hydraulic fracturing was used for the first time in Canada in the Carmiun oil field in central Alberta.

- Fracking legislation in the nation dates back to 1974, the year of enactment of the Safe Drinking Water Act SDWA, which instituted novel rules and standards for safeguarding underground drinking water sources. Despite its 25- year- long commercial use, SDWA failed to take fracking into account and was never taken into account for regulations under SDWA.

- In 1986, SDWA was amended to regulate more than 100 specific contaminants. Hydraulic fracturing, now commercially utilized for nearly forty years, is not considered for any new regulations and amendments.

- In 1994, the LEAF (Legal Environmental Assistance Foundation) appealed to the E.P.A.for the withdrawal of authorization to conduct underground injection control in Alabama, contending that SDWA necessitated E.P.A. regulation of fracking (Rahm, 2011). ThenEPA Administrator (and later President Obama’s climate and energy advisor) Carol Browner stated that “E.P.A. does not regulate – and does not believe it is legally required to regulate – the hydraulic fracturing of methane gas production wells under its U.I.C. program (under the Safe Drinking Water Act).” ( Fisher, 2010). In that same document, Browner says there was “no evidence” of hydraulic fracturing contaminating groundwater.

- In August 1996: SDWA was amended again to emphasize sound science and standards. Hydraulic fracturing is not considered for regulation.

- In 1997, LEAF appealed E.P.A.’s position (in LEAF v. U.S.A. E.P.A.) on Alabama’s U.I.C. program, arguing once again that the Safe Drinking Water Act requires E.P.A. to regulate hydraulic fracturing of coalbed methane.

- By 1999: In reply to the LEAF decision, the State Oil and Gas Board of the State of Alabama promulgated new rules and regulations on hydraulic fracturing, which the E.P.A. approved a year later. LEAF appeals the Board’s new regulations to the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The Court ultimately sides with E.P.A. and the State Oil and Gas Board of Alabama, agreeing that the state’s regulatory system is an “effective program to prevent endangerment of underground drinking water sources.”

- P.A., in 2000, initiated its study of fracking. Using only 0.5 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of production, natural gas from shale (Kbledsoe,2013) roughly accounts for one percent of America’s total natural gas production.

- In August 2002, E.P.A. released a draft of its study of hydraulic fracturing, which affirms that the technology does not pose a risk to drinking water. E.P.A.’s conclusion that fracking did not merit further research. (Wise. 2009)

- In June 2004: E.P.A. completed a four years study on hydraulic fracturing. This study began under the previous administration, which determined that fracking technology poses only a “minimal” threat to water supplies and that there are “no confirmed cases” linking hydraulic fracturing to drinking water contamination. (Peiserich, 2012)

- The 2005 Energy Policy Act provides for the unintentional codification of fracking regulation by the SDWA. Three years later, large-scale sampling and examinations by the COGCC (Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission) indicated no drinking water effects of gas and oil (Davis, 2012). This year also witnesses the “Halliburton loophole’, which exempts fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act. This loophole established that in a two-hectare site, up to 16 wells can be drilled, servicing up to 1.5 square kilometers in area and using more than 300 million liters of water and additives. It also enables around one-fifth of the fracking fluid to flow back up the well to the surface in the first two weeks, with more continuing to flow out over the lifetime of the well.

- The year 2009 witnessed several house representatives, with Democrat Colorado representative Diana DeGette, at the head, introducing FRAC, intended to rewrite SDWA goals. However, it was rendered unsuccessful by opponents who claimed the proposal aimed at creating a novel, possibly- intrusive regulatory initiative (Heikkila et al., 2014). Meanwhile, state regulators from across the country defend the safety record of hydraulic fracturing. The U.S. House of Representatives introduced the Fracking Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals Act to repeal fracking’s other exemption from the SDWA, Clean Air, and Clean Water Acts in 2005. The act never came to a vote.

- In 2010, Wyoming ratified legislation necessitating disclosing additives utilized in fracking. In the same year, Arkansas implemented novel regulations necessitating disclosing additives utilized in the fracking process, a step taken by Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Michigan, and Montana in the following year.

- In 2011, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, and Montana opted for regulations to disclose hydraulic fracturing fluids and additives used during hydraulic fracturing. Colorado and Texas utilize the FracFocus website to implement their laws regulating fracking.

- During President Obama’s State of the Union address in 2012, natural gas production from shale was strongly supported. A few months later, the E.P.A. issued a draft report claiming no proof of fracking contaminating drinking water (Konschnik & Boling, 2014).

- In December 2019, E.P.A. temporarily expanded the voluntary self-audit and disclosure program for upstream oil and natural gas facilities (E.P.A., 2012), allowing existing owners to find, correct, and self-disclose Clean Air Act violations.

- In 2022, Biden’s administration allowed fracking in all offshore oil and gas wells leased in federal waters off California. The 9th Circuit’s June ruling uncovered that the federal government violated the National Environmental Policy Act, Endangered Species Act, and Coastal Zone Management Act. The appeals court order prohibits the Department of the Interior from allocating fracking permits until it completes the Endangered Species Act consultation and an environmental impact statement that “fully and fairly evaluate[s] all reasonable alternatives.” The decision resulted from three separate lawsuits filed by the Center, the state of California, and other organizations. (Center for Biological Research, 2022) .Center scientists have found that over ten fracking chemicals routinely used in offshore fracking can kill or harm diverse marine species, including sea otters and fish. The California Council on Science and Technology identified some fracking chemicals as the most toxic in the world to marine animals.

- As November 7, 2022, SB 112-02: Fuel Inflation Reduction Act, considered the most significant climate legislation in U.S. history, is under debate. Section 3 about fracking states that: Beginning on January 1, 2025, the practice of hydraulic fracturing for oil and natural gas is prohibited on all onshore and offshore land in the USA. Nevertheless, the president may suspend this section during a declared state of emergency.

3. THE PROBLEM

One of the primary pollutants released in fracking is methane, a greenhouse gas that traps 25 times more heat than carbon dioxide. Research indicates that the U.S. oil and gas industry emits 16.9 million metric tons of methane yearly, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA, 2022). Some methane is inadvertently leaked via defective equipment or intentionally released into the atmosphere between extractions. E.P.A. estimates that the U.S. accounts for more methane emissions than 164 countries combined. (E.P.A., 2021). Without a comprehensive policy, these irregularities continue unchecked throughout the nation.

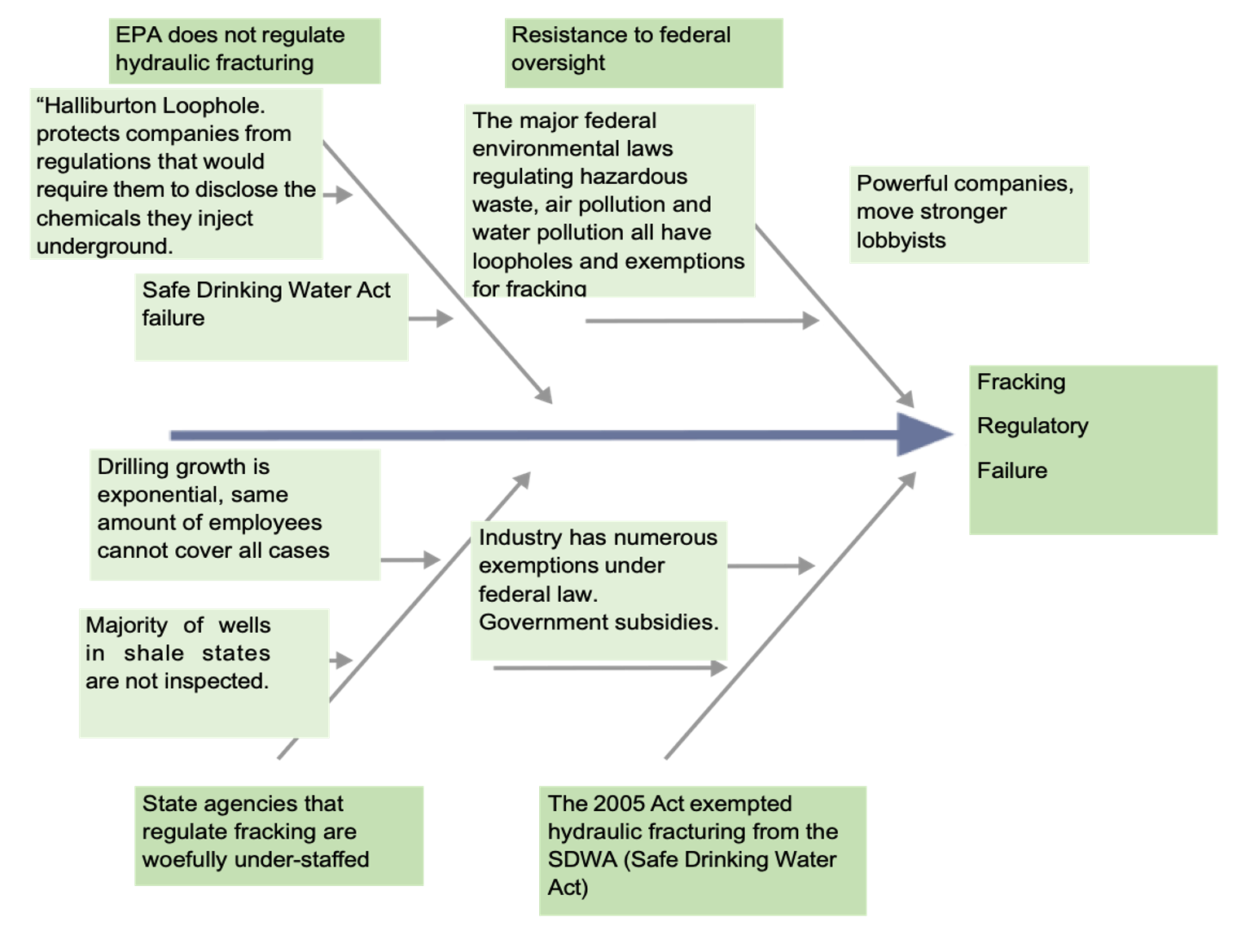

3.1 ISHIKAWA DIAGRAM

The following Ishikawa diagram illustrated in figure 1, exposes the problems, causes, and sub-causes of the policy problem. Fracking, to date, is not federally regulated. The Ishikawa diagram reflects directly on the government and its capability to create comprehensive regulations at the federal level. All this lack of regulations is fueled by the market, the high demand for energy in the USA, and lower oil prices. The primary federal environmental laws regulating hazardous waste, air, and water pollution have vital loopholes and several exemptions for fracking and other oil and gas enterprises.

As we have seen from the Fracking timeline, EPA does not control nor regulate hydraulic fracturing under its groundwater protection laws or Safe Drinking Water Act due to an amendment to the 2005 Energy Policy Act. the “Halliburton Loophole.” (Alcanzare, 2015). This loophole protects companies like Halliburton from regulations requiring them to disclose the chemicals they inject underground. State agencies that regulate fracking are understaffed, creating a lack of control and inspections. Fracking grows exponentially while agency member remains, usually the same over the years.

Figure 1: Ishikawa Diagram

3.2 RECAP OF THE PROBLEM

Environmental impact assessment should be done before all fracking and even exploration operations. Faulty wells pose a significant risk of pollution. Consequently, the quality of construction of a well must be regulated effectively. Toxic substances and effects from fracking activities, such as radioactive elements, need proper disposal; thus, the US government needs adequate regulation. For instance, disposing of water underground should be outlawed.

In order to make the policy stronger, fracking companies should be required to deposit enough bonds to cover possible compensation claims in the future. Such bonds should also be sufficient to cover the cost of cleaning up once the well’s lifecycle ends. Failure to have such bonds and resources for restoring and cleaning open coal mines is already a major environmental and social problem that fracking can use as a guide. The local governments, federal and environmental institutions like the EPA should work together to build water management plans specific to projects to prevent the wastage of water, taking into account communities, their needs and afflictions. They should be required to ensure that water flows can be traced. Such plans should consider the effect of the various seasons on water availability. Design plans to manage emissions into the air and minimize their operations’ negative impact on the communities and biodiversity. Harness gases for later use, reduce flaring, and prevent venting. Operations need to ensure that emissions of air at the stages of explorations and production are reduced by gas capturing and using it subsequently. Air pollutants such as methane should be restricted to critical operational purposes for the sake of safety (Jackson et al., 2011). An explicit disclosure of chemicals used and a ban on using trade secrets to conceal chemicals used in oil and gas extraction are necessary to create mitigation plans and guarantee the communities’ safety.

Create risk management plans and institute measures to mitigate and reduce effects, including response plans. Report any incidences and accidents that would affect the communities to the competent authorities immediately when they happen. Such a report should incorporate the cause of the incidence, the effects, and the remedial steps. Finally, those agencies regulating fracking operations at State and Federal level need an injection of trained human capital to supervise better and enforce all possible changes.

3.3 CONTEXT AND IMPORTANCE OF THE PROBLEM AND SOLUTIONS.

Hydraulic fracturing, horizontal drilling, and shale-gas extraction would gain from:

- Better scientific study and coordination of all stakeholders.

- Reviewing possible health consequences of methane and similar hydrocarbons found in drinking water.

- Industry-guided approaches for the development of safer and consistent technologies for extraction.

- Possible strengthening of federal and state regulation. Other related areas of interest not discussed in this paper but would gain from further research include the disposal and treatment of wastewater. The practices include the treatment of wastewater and release into rivers and surface streams or injecting waste into the earth.

As the USA continues to invent new methods of accessing energy resources that have not been used before, methods such as hydraulic fracturing increase in usage for the extraction of oil and gas reserves. Questions raised in this paper are set to be asked more frequently. A holistic approach to industry regulation and supervision using empirical data based on relevant federal and state oversight will chart a positive direction for energy extraction technologies for the future.

3.4 ANALYSIS, KEY FINDINGS AND RISKS:

Maintenance of the current state of affairs about free market rules and governmental policies will potentially continually check short-run public expenses. However, it will not contribute sufficiently to furthering response to concerns about hydraulic fracturing’s possible negative impacts on communities and nature. Natural gas supplies will constantly grow, constraining the growth of energy rates or lowering them and possibly generating income from forex. If the community and environmental concerns go unsubstantiated, at the very least, economic growth will not be impacted, and public expenditure will have been curbed.

Nevertheless, the substantiation of the above concerns will render extant policies too little too late, leading to potential acute environmental damage or bankruptcy of communities addressing bust-boom impacts. Relevant policy alternatives include federal laws, conditions mandatory for fracking operators, chemical disclosure conditions, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) supervision and monitoring, drilling site limitations, water supply-linked requisites, and the procurement of an ample number of competent regulators. Fracking’s continued air pollution leads to climate change and health risks. Table 1 shows risk identification for stakeholders.

| Who is involved? | Describe the vulnerability |

| Federal Government | • Lobbyists working for large oil companies pouring millions into traditional fuel energy.

• Congress people and their alliance with the oil companies. • Companies which get government subsidies, and misallocated resources. • Previous regulations and existent loopholes that benefit oil companies. Increase reliance in foreign fossil fuels. |

| State Governments | • Lost of income from the fracking industry • Jeopardizes newfound ways of energy securities

Shortage of oil and gas production and distribution |

| APA and other

Environmental Agencies. |

• Zero control over fracking

• Lack of accountability of oil companies Lack of disclosure about chemicals used and methods |

| Oil and gas Industry | • New regulations can decrease earnings making the industry unprofitable under their standards.

Lack of innovation to ensure a transition that abides to possible change on policy. |

| Communities and People | • Contaminated water,

• Seismic problems in fracking regions • Low power compared to oil companies Most people don’t care as long as gas price is low in the pump. |

Table 1: Risk Identification of stakeholders

4. THE SOLUTIONS

The country, especially those communities affected by fracking, needs a policy change at all power levels. By amending the SDWA to change the frustratingly and nearsighted Energy Policy Act of 2005, the EPA would be given the discretion to set rules for acceptable parameters on contamination levels for chemicals and technology used in fracking and control gas-oil companies’ activity. A new bill to regulate the fracking industry would also be a reasonable option. Nevertheless, small steps are welcome, considering the speed of changes in the last decades. For consideration, we present the recap of the solutions analysis on table 2 and the solution matrix on table 3.

Solution Analysis Table

| Stakeholders | Implementation

Steps |

Required Capabilities |

| Federal Regulation

|

Congress, Legislative, executive and judicial branches

|

Create comprehensive regulations for fracking so they are part of the clear act water.

|

| State Governments

|

Governors, legislative branch of the State’s

Governments

|

Enforce the federal regulations and avoid loopholes. Train human capital, create a bonds system to guarantee safe operations. Train human resources and hire more supervisors.

|

| Environmental

Protection Agency – (EPA) |

EPA board, General Administrator, State administrators | Assessment of the potential impacts of oil and gas hydraulic fracturing activities on the quality and quantity of drinking water resources in the United States

|

| Communities | Affected

Communities, Environmental activists, advocates. |

Communities need more involvement in opposition to unregulated practices. There are plenty of ways to make their voice heard at the

federal, state, and local levels to create awareness of Environmental Justice. |

Table 2: Recap of the solution analysis

Solution Matrix

TechnicallyCorrect |

Politically Supportable |

Organizationally Implementable |

|

Solution 1FederalRegulation |

A federal regulation to which all States abide to and it is equal for all. |

To date, the government has not been able to implement a fracking policy. At this point, something radical will need tohappen to motivate the change |

In the USA, we have environmental agencies capable to take care to implement a federal policy that right now, cannot act or do not have a saying in the subject like EPA |

Solution 2Federal Disclosure of procedures and chemicals used |

Disclosure of chemicals and procedures used so we know what it is getting injected in our soil and its effects. |

Companies have found loopholes in previous regulations to continue perforations and do not disclose their procedures, it will all depend in the lobbyist and initiative that congress people may take |

Once companies are enforced to disclose procedures and chemicals used in all fracking fields, environmental agencies and regulation can change their operations to meet the best interest of the people |

Solution 3Worktogether |

The local governments, federaland institution like theEPA, TheDepartment of Energy (DOE), TheDepartment of the Interior- The U.S. Fish and WildlifeService (FWS),National Park Service, USGS should work together so they can build water management plans |

It will be easier to implement a federal policy or changes in the regulation if the federal environmental agencies like the Department of Agriculture, Department of Energy, U.S. Environmental ProtectionAgency, Fish and Wildlife Service,Forest Service, Geological Survey,National Oceanic and AtmosphericAdministration, National WeatherService, the federal government and State governments work together. They will get all the support needed to implement a possible policy implementation and change. |

They should be required to ensure that water flows can be traced. Such plans should consider the effect of the various seasons on water availability. Design plans to manage emissions into the air and minimize their operations’ negative impact on the communities and biodiversity. Harness gases for later use, reduce flaring, and prevent venting. Operations need to ensure that emissions of air at the stages of explorations and production are reduced by gas capturing and using it subsequently. Water deserves special attention, not only the ground currents but also those underground. |

Status Quo |

Keep the regulations as they are so every State is responsible to execute and implement their own policies. |

Each State should be responsible for the outcome of its regulations, and the central government should keep a Status Quo in the current regulations or the lack of regulations. |

Everything remains the same, and it is up to each State government to generate changes and regulations or keep the Status Quo. |

Table 3: Solution Matrix

4.1 BASIC THEORY OF CHANGE

In order to complement federal and state laws, additional complexity materializes when jurisdictions overlap or even work together, which makes the policy weak. Concerning hydraulic fracturing, federal laws are usually administered by the B.L.M. (Bureau of Land Management) and E.P.A. Nevertheless, E.P.A. might assign some of its power to state-level legislation making a solid move toward a federal policy. The fracking sector in the U.S.A. requires a federal law designed to regulate and govern it. One of the possible laws that should be turned into legislation is the FRAC Act. If there is no legally binding and effective legislation, communities and the environment in the U.S.A. are bound to remain unprotected creating uncertainty. Below, in table 4 we present the log frame in the theory of change

| Input |

Federal regulations on fracking |

Congress approves a federal regulation, all states and companies involved change their operations within the assigned time frame. |

| Output |

Equal regulations in all states, regulation on chemicals and procedures used. |

Change in legislation stops the already existent loopholes used by energy companies. Disclosure or chemicals used |

| Output or Outcome |

EPA gets involved at a federal level. Clean water act regulates fracking. |

The clean water act and intervention of EPA should create a more comprehensive policy in the country. |

| Outcome |

Companies stop the loopholes in regulations and disclose valuable information about the chemical used. |

Knowing procedures and chemicals used, helps mitigate the pollution and penalizes any wrongdoing by companies. |

| Impact |

Stop pollution of underground water and soils, decrees air pollution, preserve nature. |

Pollution reduces, earthquakes are not generated, water remain clean, new technology develops to comply regulations. Communities have a better chance for Environmental Justice. |

Table 4: Log frame in the theory of change

5. STAKEHOLDERS AND INTERESTS/INCENTIVES

When it comes to fracking, we encounter several stakeholders. Each holds different interests, and they get motivated by different outcomes regarding the future of fracking. Table 6 exposes how these players get affected by possible solutions that may be adapted when changing the fracking policy and their interests in the solutions.

| Stakeholder | How is this stakeholder affected by the solution? How can this stakeholder affect its adoption? | Interests/Incentives: What does the stakeholder care about? Is their interest in the solution high, medium, or low? |

| Federal government |

The federal government wants to wash its hands and leave fracking regulation to State governments. |

The federal government’s interests and incentives to find a solution are low. Too often, Washington ignores the complexities inherent in our vast and diverse nation and reverts its decisions to a one-size-fits-all approach in which Washington “knows” best.For them, the fundamental question is: Who is best suited to protect the health and safety of each region — State regulations, experienced regulators, geologists, or somebody in Washington? Unfortunately, anyone but them. |

| Local governments |

Local governments enjoy the status quo expecting more funding and the generation of more revenue for their States. |

The state government’s interests and incentives to find a solution are low. In the Eyes of State regulators, they assume that they know their natural resources. They know the local geology, geography, and production characteristics, making them better suited to regulate local energy producers than remote federal bureaucrats. Their interest is focused on bigger and better revenues and more federal funding to take care of the issues generated by fracking |

| EPA and other

Environmental Agencies |

EPA and other environmental agencies need to have enough power to control fracking. Right now, it has none, and the industry has found loopholes and benefits from the lack of federal regulations. |

The environmental interests and incentives to find a solution is high. EPA and other agencies should regulate and track many fracking wells, which will challenge current industries. There is a need to deploy enough staff to provide resources for practical work. It has been noted with concern recently that EPA staff have been reduced over the years. Regulators should also have enough expertise in all fracking-related issues, including well safety (Heikkila et al., 2014). More funding will be allocated to environmental agencies. |

| Affected

Communities Environmental activists |

EPA needs to have enough power to control fracking, right now, it has non and the industry has found loopholes all over. |

The environmental interests and incentives to find a solution is high. Public health, districts affected by fracking, and environmental justice supporters demand adequate policy solutions and partnering with affected communities. The solutions should feature the leadership of Indigenous advocates, scientists, and policy experts addressing the disparate impact of fracking on their nations and communities by designing innovative legal and advocacy approaches and alternative resolutions in which they are involved directly. |

| Companies involved in Fracking |

Any possible regulation, affects the economic gain of oil-gas companies involved in the fracking industry |

The environmental interests and incentives to find a solution is extremely low. They are interested to delay any possible regulations to maximize profits. |

Table 6: Stakeholders interests and incentives

5.1 STAKE HOLDERS RELATIONSHIP.

- Companies producing oil through fracking – Federal government. The country needs more oil to stop depending on foreign energy’s the companies are willing to help as long as regulations make the endeavor highly profitable. A similar situation occurs with state governments.

- The federal government – state government. No explicit agreement on who is in charge of the regulations. Local Governments cannot go against the federally created loopholes in the regulations, which companies take advantage of.

- EPA and Environmental Agencies- Local and Federal governments. EPA needs more power and new regulations to tackle the issue. They have the Environmental expertise but need more power or resources allocated to make the changes.

- Communities – Everybody else. Communities have the lower hand at the bargaining table. Minority communities are disproportionately located near and thus negatively impacted by shale oil. Communities and activists have pursued redress through the court system and their government representatives. The story of fracking illustrates the critical role played by regulated interests that prefer the state to federal regulation, resulting in a variable, often weak state or federal regulatory regime.

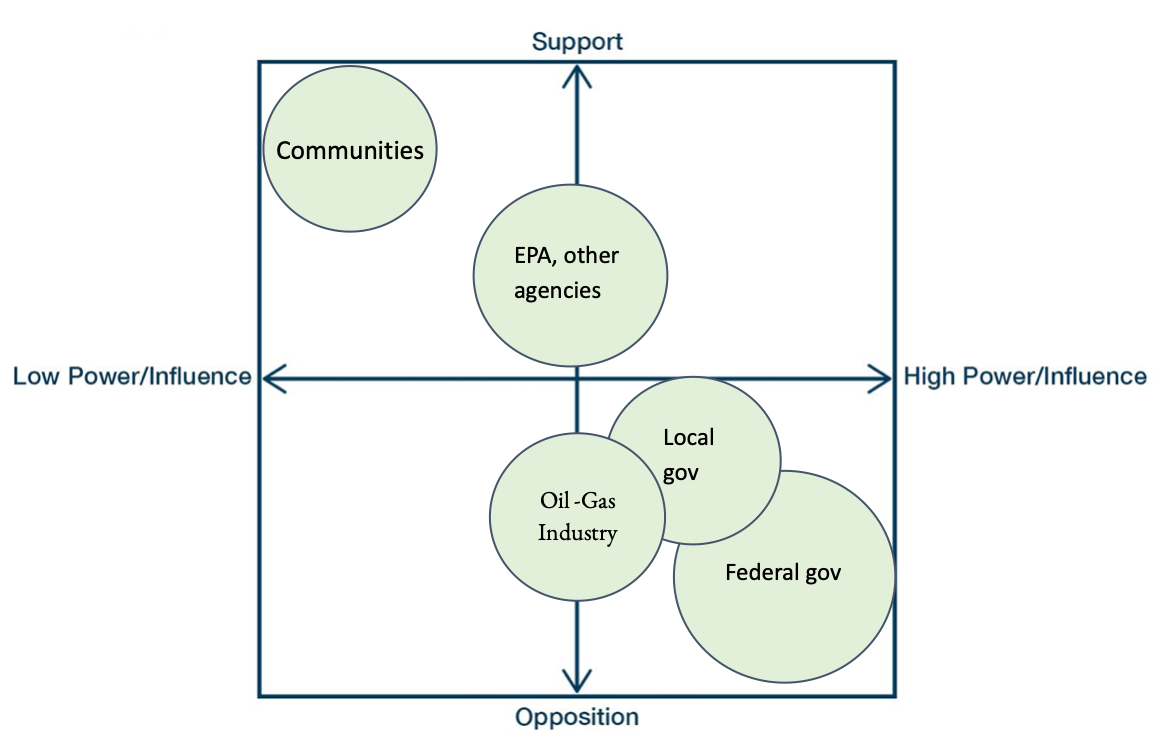

5.3 POWER/SUPPORT MATRIX

The political supportability solution based on the stakeholder analysis can be interpreted in the Power/ Support Matrix analysis below. The Federal government is the “big player.” Nevertheless, for decades they have shown negligence in supporting any change. They have not explicitly opposed changes but just made themselves invisible at the time to create modifications. That attitude alone makes them stand at the top of the opposition. State Governments and OilGas companies enjoy the Status Quo, which benefits their revenue. Oil companies lobby to keep the federal government bouncing around regulations that never come to effect or find loopholes to operate. With a low power of influence and the most benefit from possible changes in fracking policies are the communities and activists who have created enough buzz to modify several states’ regulations. Still, their power and economic-lobby importance have yet to reach the ears of the federal government. We can deduce that fracking policy proposals and regulations on this issue have been fueled by its exemption from the Safe Drinking Water Act. The development of this policy involves the introduction of proposals by several sponsors, committee discussions, reports, and floor debates in both houses of Congress. However, policymakers have faced numerous difficulties and failed to date in enacting federal regulations on fracking, as seen in the timeline exposed above. The policy recommendations in this paper are made to make the extraction of natural gas consistent and safer among the extracting companies, communities, and regulating entities at all times and locations. Making decisions relating to the extent of extraction of natural gas regulation must incorporate safety, public health, the need for more energy, and regulation bureaucracy. Research shows that hydraulic fracturing, horizontal drilling, and shale gas extraction would gain from

- Better scientific study and coordination.

- Reviewing possible health consequences of methane and similar hydrocarbons found in water for drinking.

- Industry-guided approaches for the development Involvement of the affected communities.

Graphic 2: Power Support Matrix

5.4 ADDITIONAL ANALYSIS

Currently, several environmental laws are seen as having their origins in the federal sphere. Though numerous federal environmental legislations would typically include fracking, several include general gas, oil operational exemptions, and even fracking-specific ones. Exemptions to produce natural gas are authorized under SDWA regulations, the CWA or Clean Water Act, RCRA (Resource Conservation and Recovery Act), and the SDWA’s UIC (Underground

Injection Control) – a regulatory system to inject fluids underground (Obold, 2012). In the same way, Naturally Occurring Radioactive Materials (NORM) do not, as a rule, come under federal regulatory limitations for radioactive material disposal. Thus far, natural gas production emissions were generally below the necessary thresholds for triggering federal air regulation as part of the CAA (Clean Air Act. However, the newly implemented gas well-targeted NSPS (New Source Performance Standards) would need to employ emission control techniques at wells. Its implementation is, at present, pending litigation, with specific provisions in the reassessment phase (Linkov et al., 2014; Ferrell & Sanders, 2013). No federal requisites are in place to mandate disclosure of fracking fluid contents. Still, the BLM (Bureau of Land Management) has put forward a regulation requiring disclosing these fluids’ contents if they are to be utilized on lands it manages.

Furthermore, no less than three congressional bills have been put forward. These bills delegate authority to state governments for the imposition of conditions. The FRESH (Fracturing Regulations are Effective in State Hands) Act) or creating federal disclosure conditions (i.e., the FRAC (Fracturing Responsibility and. Awareness of Chemicals) Act).

Exemption of these facets of natural gas extraction from federal regulation paves the way for state directives. Except for federal law preemptions and prohibitions, states can enact environmental laws, which are, at the very least, as environmentally appropriate as the federal regulations. Municipalities, counties, regional authorities, and some states have enacted “moratoria” on natural gas mining undertakings (Romo, 2014; Sanders & Ferrell, 2013). Such moratoria are generally phrased as short-term and pending the result of specific state reports on the green impacts of methods like hydraulic fracturing. Some other states in the US regulate particular components involving gas extraction procedures.

In addition to federal and state laws, additional complexity materializes when jurisdictions overlap or work together. Regarding hydraulic fracturing, federal laws are usually administered by the BLM and EPA. Nevertheless, EPA might assign some of its power to demand states, described as “collaborative federalism” (Romo, 2014; Sanders & Ferrell, 2013). Finally, municipalities and counties might also have experts in environmental regulatory issues through state regulatory authority. These specialists will help to act through not only health units but also other environmental departments or, in some cases, as “de facto” environmental authorities acquired indirectly via zoning, land usage, along with construction permitting activities (Theodori et al., 2014, pp. 44-46).

6. POLICY RECOMMENDATION

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) Underground Injection Control Program is intended to preserve drinking water from contamination by requiring the EPA or EPA‐authorized states to implement programs that prevent the underground injection of fluids from endangering drinking water. Even though hydraulic fracturing involves the underground injection of fluids, the EPA has never regulated hydraulic fracturing under the SDWA. The 2005 Energy Policy Act codified this by specifically excluding “the underground injection of fluids or propping agents (other than diesel fuels) under hydraulic fracturing operations related to oil, gas, or geothermal production activities” from the definition of “underground injection. Even though diesel was the one explicit additive that still required an underground injection control (UIC) permit when the US congress exempted all other additives from the SDWA, in 2005, diesel was still heavily used between 2005 and 2009 (Elsner, 2016). The use of diesel was discontinued after 2011.

Natural gas companies are not required to disclose the identity of the chemical constituents in hydraulic fracturing fluid under federal law or most state laws and guard the makeup of hydraulic fracturing fluids as a trade secret. Requesting information on the chemical composition of hydraulic fracturing fluids as part of their ongoing study of hydraulic fracturing, indicating that they had the legal authority to compel disclosure if necessary. At this point, it becomes crucial that a federal regulation can be enacted to complete this policy.

6.2 REGULATIONS NEEDED

- One of the possible laws that should be turned into legislation is the FRAC Act.

- The fracking sector in the USA requires a federal law designed to regulate and govern it. If there is no legally binding and effective legislation, communities and the environment in the USA are bound to remain unprotected.

- Better coordination by all stakeholders and sustained scientific studies

- Environmental impact assessment should be done before all fracking and even exploration operations. Faulty wells pose a significant risk of pollution. Consequently, a well’s construction quality must be regulated effectively (Clark et al., 2012). Toxic substances and effects from fracking activities, such as radioactive elements, need proper disposal; thus, the US government needs adequate regulation. For instance, disposing of wastewater underground should be outlawed.

- A review of the potential health consequences of methane and other hydrocarbons in drinking water is necessary.

- Fracking companies should be required to deposit enough bonds to cover possible compensation claims in the future. Such bonds should also be sufficient to cover the cost of cleaning up once the well’s lifecycle ends. Failure to have such bonds and resources for the restoration and cleaning of open coal mines is already a major environmental and social problem in the state of Colorado (Heikkila et al., 2014).

- Consider more vital state or federal regulations where communities can have input at all decision-making stages.

- Industry‐driven approaches to develop safer and more consistent extraction technologies

- Chemical risk analysis regarding fracking should also focus on the effect of leakage from wells, the piping above the ground, storage, and transportation. These are clear and predictable risks (Finkel et al., 2013).

- Manufacturers and distributors of substances of chemical nature must disclose and communicate all the possible human exposure scenarios anticipated for substances of fracking. Clear precautionary measures must be stated on any assumptions made in the calculation of the actual adequate control, such as in the cases of storage and flow-back issues (Theodori et al., 2014).

- There is a need to deploy enough staff to provide resources for effective work. It has been noted with concern that EPA staff have been reduced over the years. Regulators should also have enough expertise in all fracking-related issues, including well safety (Heikkila et al., 2014).

- Fracking activities should never be carried out near key wildlife sites or underneath, including protection areas such as special protection and conservation areas, Special Scientific interest sections, and National parks (Jenner & Lamadrid, 2013; Jackson et al., 2011). Potential pollution of groundwater sources should be noted seriously, and the protected groundwater zones should be shielded from fracking operations.

- Local communities should have input in making decisions regarding fracking in their areas.

6.3 MONITORING

- Fracking operators should carry out thorough water and air monitoring within the vicinity of their working sites before, during, and after they have finished their operations. Such a measure will guarantee clear baselines and subsequent pollution is detected

- Independent geology and groundwater protection experts should continuously inspect to oversee well construction that does not pose a pollution risk. They should ensure that toxic materials are properly disposed of (Evensen, 2015). It should be noted that even where wells are sealed after exhaustion, they are still potential groundwater polluters. Therefore, resources must ensure the remediation of problems if they arise.

- Systems to detect emerging adverse health effects of fracking activities on the workers at the site, the area residents, wildlife, plants, and livestock should be set up (Theodori et al., 2014).

7.0 CONCLUSION

We live in the shale revolution, and new technologies are speeding up the extraction of oil and gas. However, countries worldwide, especially the USA as the biggest producer, face severe problems with their policy and regulations. The concerns raised go beyond groundwater contamination during the fracking process; they include earthquakes, harmful impacts on the air, climate stability, farming, public health, property values, and the financial vitality of communities. These issues are likely avoidable problems as new technologies develop. Nations and politicians should be happy to have large new proven gas reserves. While these benefits are apparent, further research is still needed to establish how water is contaminated and how methane is lost to the atmosphere. Further, there is a need for extra oversight to protect the environment and communities from water contamination in areas bordering disposal and extraction sites. The scientific examination by environmental groups and activists found no evidence that fracking extraction can be practiced in a manner that does not endanger communities’ health directly and without threatening the environmental stability upon which public health depends. Nevertheless, our leaders should find a balance and review current policies.

Fracking policy proposals and regulations on this issue have been fueled by its exemption in the Safe Drinking Water Act. The development of this policy issue involves the introduction of proposals by several sponsors, committee discussions and reports, and floor debates in both houses of Congress. However, policymakers have faced numerous difficulties and failed to date in enacting federal regulations on fracking. The policy recommendations above are made to make natural gas extraction consistent and safer among the extracting companies at all times and locations. Making decisions relating to the extent of extraction of natural gas regulation must incorporate safety, public health, the need for more energy, and regulation bureaucracy. As the USA continues to develop new methods of accessing energy resources, methods such as hydraulic fracturing increase in usage for the extraction of oil and gas reserves, questions raised in this paper are set to be asked more frequently. A holistic approach to industry regulation and supervision using empirical data based on relevant federal and state oversight will chart a positive direction for energy extraction technologies for the future

REFERENCES

Alcanzare, D. (2015). FRAC to the Future: The Application of the SDWA to Biodiesel use in Hydraulic Fracturing. LSU J. Energy L. & Resources, 4, 407.

Clark, C., Burnham, A., Harto, C., & Horner, R. (2012). Hydraulic fracturing and shale gas production: technology, impacts, and policy. Argonne National Laboratory.

Cotton, M. (2017). Fair fracking? Ethics and environmental justice in United Kingdom shale gas policy and planning. Local Environment, 22(2), 185-202.

Cupas, A. C. (2008). The not-so-safe drinking water act: why we must regulate hydraulic fracturing at the federal level. Wm. & Mary Envtl. L. & Pol’y Rev., 33, 605.

Davis, C. (2012). The politics of “fracking”: Regulating natural gas drilling practices in Colorado and Texas. Review of Policy Research, 29(2), 177-191.

EPA, 2012. Unconventional Oil and Natural Gas Development | US EPA.

https://www.epa.gov/uog

EPA, 2021. November 2, 2021. Press Office “US to Sharply Cut Methane Pollution that Threatens the Climate and Public Health.” https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/us-sharply-cut-methane-pollutionthreatens-climate-and-public-health

Elsner, M., & Hoelzer, K. (2016). Quantitative survey and structural classification of hydraulic fracturing chemicals reported in unconventional gas production. Environmental science & technology, 50(7), 3290-3314.

Evensen, D. T. (2015). Policy decisions on shale gas development (‘fracking’): the insufficiency of science and necessity of moral thought. Environmental Values, 24(4), 511-534.

Ferrell, S. L., & Sanders, L. (2013). Natural gas extraction: Issues and policy options.

National Agricultural and Rural Development Policy Center.

Finkel, M., Hays, J., & Law, A. (2013). The shale gas boom and the need for rational policy. American journal of public health, 103(7), 1161-1163.

Fisher, K. (2010). Data confirm safety of well fracturing. The American Oil & Gas Reporter, 1-4.

Global Research, 2022. Biden Administration Backs Offshore Fracking in California. https://www.globalresearch.ca/biden-administration-backs-offshore-fracking-california/5792016.

Heikkila, T., Pierce, J. J., Gallaher, S., Kagan, J., Crow, D. A., & Weible, C. M. (2014).

Understanding a period of policy change: The case of hydraulic fracturing disclosure policy in Colorado. Review of Policy Research, 31(2), 65-87.

Hill, E., & Ma, L. (2021). The fracking concern with water quality. Science, 373(6557), 853-854.

IEA, 2022 International Energy Agency. “ Interactive database of country and regional estimates for methane emissions and abatement options” Retrieved December 12th from https://www.iea.org/dataand-statistics/data-tools/methane-tracker-data-explorer

Jenner, S., & Lamadrid, A. J. (2013). Shale gas vs. coal: Policy implications from environmental impact comparisons of shale gas, conventional gas, and coal on air, water, and land in the United States. Energy Policy, 53, 442-453

John F. Peiserich Perkins & Trotter, PLLC – Oklahoma.

https://iogcc.ok.gov/sites/g/files/gmc836/f/jfp_-_hf_chemical_disclosure_-2012_sa_0.pdf

Jackson, R. B., Pearson, B. R., Osborn, S. G., Warner, N. R., & Vengosh, A. (2011). Research and policy recommendations for hydraulic fracturing and shale-gas extraction. Center on Global Change,

Duke University, Durham, NC. current-status-federal-fracking-regulation.html>

Kbledsoe, 2013. Hydraulic Fracturing Timeline.

https://hydraulicfracturingblog.webs.com/apps/blog/categories/show/1678306-hydraulic-fracturingtimeline

Konschnik, K. E., & Boling, M. K. (2014). Shale gas development: a smart regulation framework.

Environmental science & technology, 48(15), 8404-8416.

Kramer, Bruce M. “History and Current Status of Federal Fracing Regulation.” American Bar Association. American Bar Association, 3 June 2013 Retrieved December, 2022 from http:// apps.americanbar.org/litigation/committees/energy/articles/spring2013-0613-historycurrent-statusfederalfrackingregulation.html

Linkov, I., Trump, B., Jin, D., Mazurczak, M., & Schreurs, M. (2014). A decision-analytic approach to predict state regulation of hydraulic fracturing. Environmental Sciences Europe, 26(1), 20.

Obold, J. (2012). Leading by example: The Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals Act of 2011 as a catalyst for international drilling reform. Colo. J. Int’l Envtl. L. & Pol’y, 23, 473.

Rahm, D. (2011). Regulating hydraulic fracturing in shale gas plays: The case of Texas. Energy Policy, 39(5), 2974-2981.

Romo, C. R. (2014). Hydraulic Fracturing, Uncooperative Federalism, and Technological Innovation. Geo. Wash. J. Energy & Envtl. L., 5, 1.

SB 112-02: Fuel Inflation Reduction Act (Debating).

https://talkelections.org/FORUM/index.php?topic=528602.0

Spence, D. (2014). Fracking Regulations: Is Federal Hydraulic Fracturing Regulation Around the Corner?. EMIC.

Theodori, G. L., Luloff, A. E., Willits, F. K., & Burnett, D. B. (2014). Hydraulic fracturing and the management, disposal, and reuse of frac flowback waters: Views from the public in the Marcellus Shale. Energy Research & Social Science, 2, 66-74.

Wiseman, H. (2009). Untested waters: The rise of hydraulic fracturing in oil and gas production and the need for revisit regulation. Fordham Envtl. L. Rev., 20, 115.

.