Innovation District: Boston’s “South Boston Action Plan”(2)

Innovation District: Boston’s “South Boston Action Plan”(2)

The simplicity of our career’s beginnings

will not damage its greatness at conclusion.

——Zhuangzi·Man in the World

Talent will decide the future of economic development in Boston, and holds the key to the fate of development in the world’s metropolitan areas.

——Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce

This is the third Thanksgiving I’ve spent in Boston, and I feel that the holiday spirit is stronger this year than in previous years. Cars have been parked in front of our doors by friends and relatives getting together with our neighbors to celebrate the holiday, and on the streets I keep running into happy groups of people. Even children’s playgrounds appear crowded, having added more than a few strange faces. Groups of eager and enthusiastic people converse with cheerful voices, and with rich facial expressions and animated body language, next to tables in restaurants, on the sides of roads, and at playgrounds; everyone has swept clear the reserve and quiet of their everyday lives- there is really a feeling bordering on exuberance in Boston now!

The phrase “a fall filled with troubled tidings” could be used to describe the more than one month that has just passed, and I believe that the successive series of unexpected events that occurred here over that time made everyone hold within themselves thoughts which they now wish to get off their chests and topics which can be discussed at length.

First among topics that people won’t let go of is that of late October’s storm, the once in a lifetime Hurricane Sandy; while the hurricane didn’t actually make people go wild with terror, it still did make people extremely nervous. First came the state governor announcing that Massachusetts had entered a State of Emergency, closely followed by a stream of telephone calls, text messages and emails broadcasting all types of warning information and disaster-related reminders. Television and broadcasting stations rolled out live reports on the storm center, followed by shopping centers’ disaster-related goods being completely bought up. When the storm’s strong winds and rain hit, schools stopped classes, transportation stopped, businesses closed, and rescue teams along the Greater Boston seacoast prepared to meet the challenge.

However fortunately, after making landfall on the New Jersey coast, Sandy’s winds turned left and headed westwards, so that the storm’s center only glanced by Boston. While some areas of Massachusetts suffered light storm damage, no persons lost their lives due to the storm. Rattled, but not seriously damaged, Boston did not ignore the damaged plight of its brother and sister cities; Boston mayor Thomas Menino immediately sent well-prepared teams to New York to be immediately put into use in local disaster rescue and relief efforts. The conversations I hear now no longer discuss the “luck” that we had, as they did during the “nervous” times before the storm as well as after it hit, but now mostly concern the fact that ‘we can’t always be this lucky, what will we do the next time a “Sandy” comes? What preparatory work should we start to carry out now?

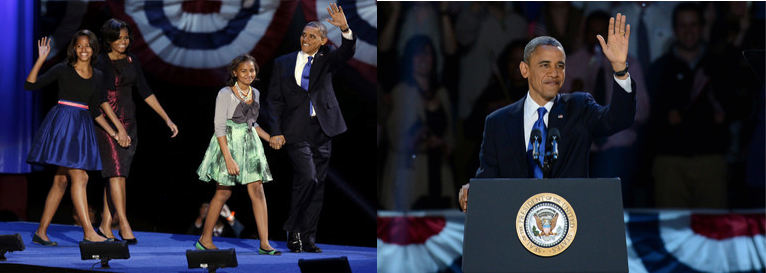

Another often-mentioned topic is of course that of the political elections that have just ended. In Massachusetts, everyone, in addition to paying attention to the presidential election, placed even greater attention on the election results for the US House of Representatives and Senate Positions, and the most gripping of these races was the struggle for one of the state’s senate seats in the US Senate. Romney’s current domicile is Massachusetts, he served as Massachusetts State Governor in the past, and he also made his election headquarters in the Boston area, however everyone was deeply aware that he had no chance of victory in Massachusetts, called a base of the Democratic party, and the only question with the presidential election results in Massachusetts was that of just how many votes he would lose by.

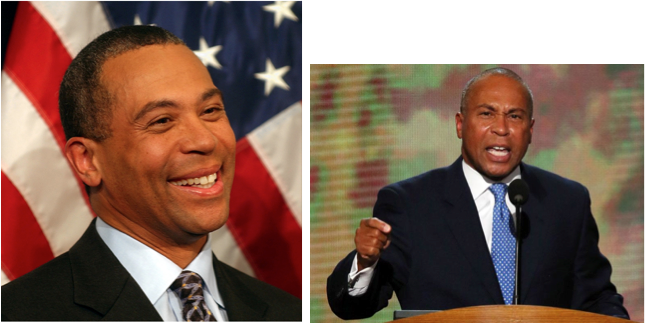

In fact it was the election contest between female Harvard University Law School professor Elizabeth Warren and Republican Party Senator Scott Brown that was fiercely contested, with polling results from polling organizations before the elections showing that voting support was extremely close for both. The election results were even more surprising, with the Democratic Party candidate, 63 year old Warren, winning a clear victory, 54% to 46%, over the “Tall, Handsome and Rich” Brown- who had already served for two years as Senator-, winning the most expensive election for US Senate in history (the two candidates spent almost 80 million US dollars in campaign costs)!

Whether discussing Sandy or the election, everyone comes to mentions one of Massachusetts’s political stage’s most important characters-Boston’s Mayor Menino.

* * *

If discussing Menino in connection with Sandy, people would first praise his planning and calmness in the face of the approaching natural disaster, and secondly express worry about his and Boston’s future development. The concern is not only about Menino’s physical health, although this is a concern indeed- since cutting short a vacation in Italy due to illness on October 26, he has continuously been in the hospital receiving treatment. Although from time to time he uses the media to release news that he is gradually getting better, it seems that the outlook is not positive, and people indeed have cause to express deep concern and wishes for his physical health.

After hearing and seeing the awful plight of disaster areas such as New Jersey and New York City after the assault by Sandy, even more people have begun to sweat over the Innovation District construction project which Menino has actively promoted. The worry is, when the Innovation District is completed after several years, with its position on the coast in South Boston’s wharf district, if the Innovation District were to be hit by a storm equally as strong as Sandy, what would the result be? Would current safeguards be enough to successfully stop the sea’s rise and storm winds from causing negative influence and damage? As he sits in his hospital room reading and approving official documents, Mayor Menino, who has continued to be clear of mind, has certainly heard the worries and calls from the citizenry regarding this!

If discussing the election in regards to Menino, everyone, without exception, expresses their conviction and admiration for him. In regards to the election for US Senate, Menino was, from the beginning of the campaigns, in a very delicate and sensitive territory. Brown is a Republican, but actually happened to agree with Menino on many important topics, and the two men had established a very close personal relationship in the midst of their work together. Menino always greatly praised Brown’s ability and performance. However, although Warren- who like Menino is in the Democrat camp- was very active in the Washington area and extremely well-known nationally, didn’t have much experience cooperating with Menino in local government. At the Democratic Party National Convention, Menino didn’t clearly express support for Warren in his speech, and this made the Democratic Party unhappy and worried. Menino delayed giving his public support for Warren until September 21.

Why was obtaining Menino’s support so important? In addition to the influence that comes with being a star mayor, everyone also greatly values his charisma and organizational abilities. “They have a very capable team that can take issues to the streets”, said one Boston former City Council member, “this means making phone calls, identifying potential supporters, going door to door, etc. The work they did for Patrick (who has served as Massachusetts Governor since winning the position in 2006) was amazing! As long as they do the same for Warren, her victory is certain!” The facts of the election confirm that these words were not false!

On the day of the election, 2,289 volunteers rang the doorbells of 110,000 households, and gave citizens rides to polling places, gave free pizzas, hot coffee and hot chocolate to voters, and even used fast-food vehicles to give voters snacks such as soup and cookies, to supervise over and win votes. Election results showed that in Boston, 255,139 city voters cast votes, the most voters since 1964, and that of these 75% of voters cast votes for Warren.

After learning of the election results, Menino, in his hospital bed, couldn’t back his surprise and pleasure, and exclaimed, ” Look at Boston’s voting results, even better than the election for Patrick, this is so impressive!” Using the strength of Menino’s election machine, the Democrats not only defeated Republican Senator Brown, who had just warmed up his Senate seat and possessed great personal charm, but also ensured that all of Massachusetts’s sitting House Representatives seeking re-election were re-elected. As Republican strategist Todd Domke said in exasperation: “The reality is the Republican Party has met with widespread defeat in the entire Northeastern Region, and it was especially bad in Massachusetts.”

These two seemingly unrelated events (Hurricane Sandy response and the election), are actually both extremely connected to Menino, and thus convey a common message: when considering government administration and operation of political parties, human factors need to be considered; people really are the most important part of this equation. The Innovation District project has been a project on which Menino has labored for ten years, and although overall progress has been smooth, it seems that in the face of unexpected natural disasters, there will continue to be doubts and further re-assessments regarding the project. After all, city building’s biggest return and goal is to serve the people, and if city residents’ lives and properties are threatened (even if only potentially threatened), even the best, creative ideas will run aground no matter how much effort has been expended into them!

From this vantage point, it seems that Boston’s City Government and Menino are facing a new challenge. This election changed my original perception of the grassroots organizational power of the American government. Previously I primarily believed that it was very difficult for such loose “Election Clubs”, which can be freely entered into or left, to produce the ability to organize, mobilize and bring together constituents. However now it seems that although under the democratic structure it is still very difficult for political parties to use so-called strict discipline to control members, individual bodies with strong missions and senses of responsibility, and possessing strong contributive spirits, can very easily organize and create “a turning of the tide” and “miracles”. This also adds dramatic and theatrical results for elections’ multi-party competitive tussles.

* * *

After observing and analyzing Menino’s actions throughout the years, it seems that the label of “people-oriented, serves the voters” could be used by Menino to openly describe his idea of government administration. This kind of idea has been fully embodied in the planning and implementation of the Innovation District. The construction of the average industrial park faces two difficult choices:: either creating a good environment and then looking for businesses, or first recruiting businesses and then creating a good environment. Some people have called this a problem of “which comes first, the chicken or the egg?” In the construction sequence and in infrastructure’s function and design, Menino used a method that was close to peoples’ needs, by first starting a series of Service Park entrepreneur projects.

In April of this year, the Boston Innovation Center (temporary name, a more permanent name is still under consideration) began construction; this is the opening work for Menino in creating a good environment for the Innovation District. Total investment in the Center is 5.5 million US dollars, and it is designed to be a one-story building occupying 12,000 square feet (about 1,115 square meters), with a construction completion and opening date of spring, 2013. The Innovation Center will be comprised of a 9,000 square foot (about 836 square meters) public space and a 3,000 square foot (about 279 square meters) cafeteria. The public space will include several conference rooms, classrooms and exhibition halls, so that several types of dialogue activities, such as conferences, forums and expos/conventions, can be held. After construction is completed, this Center will be opened for free to newly created companies and their employees.

The Boston Innovation Center is responsible for the goals of promoting dialogue and communication, fostering a culture of entrepreneurship and promoting industrial development. Menino has in the past pointed out that “The Center will be the first building of its kind in Boston, and will be a core part of our city’s innovative facilities … perhaps the next billion dollar idea will be born here.” The Center’s investment came from two companies- Boston Global Investors, and Morgan Stanley-, and the government, after a period of ten years of free use, will return the handling of the Center to its developer(s) (as one of the conditions for obtaining the Seaport Square’s business license). After construction on the Center is complete, its operations will be contracted out by The Boston Redevelopment Authority to the Cambridge Innovation Center, using the cafeteria’s profits to maintain normal operations for the Center.

The Boston Innovation Center’s functions will be close to that of the Microsoft New England Research and Development (NERD) Center built by the Microsoft Corporation in Cambridge, but the Boston Innovation Center will be the first public innovation center in the nation. A difference between this Center’s functions and those of the Cambridge Innovation Center is that this center will not accept companies on a long-term basis, but will only provide companies with short-term use inside the Innovation District. The Boston Innovation Center’s construction and operation models will also display Menino’s and his team’s innovative thought processes.

How can affordable use housing be provided to employees of companies entering the Innovation District? This has also become one of the problems which Menino has made great efforts to solve. He promoted the “ONEin3” conference (a survey found that 30% of Boston’s residents are young people between 20 and 34), and has also appealed for developers to construct mini-apartments that can be rented for low prices to entrepreneurs and science and technology employees, calling these mini-apartments by the name of Innovation Units. In order to construct these Innovations Units, he has used legal processes to change the standard for apartments’ dimensions. He had to due this as the City Government’s regulations previously stated that the dimensions of Boston’s smallest apartments’ should not be less than 450 square feet (about 50 square meters), however estimates for the mini-apartments were that if rents were to be kept controlled at 1500 US dollars per month, mini-apartments containing only a kitchen, bathroom and bedroom would only be able to have dimensions of 350 square feet (about 42 square meters).

After this, the City Government invited famous design company ADD Design (ADD Inc.) to carry out full market research and come up with a specific, applicable implementation strategy for the mini-apartments. 300 “micro-units” with dimensions from 300 to 450 square feet (about 28 to 50 square meters) will, in accordance with ADD Design’s design plan, be built at the four residential projects on which construction has begun inside the Innovation District.. After construction these mini-apartments will be rented out at low prices to the government to help the government attract young entrepreneurial talent and the “creative class” to come live in them.

Under the unremitting efforts of Menino and the Innovation District’s management team, the Innovation Disctrict’s environment has obtained clear improvements. Several specialty cafeterias, bars, etc. have opened one after another, communication and internet service providers have energetically opened services, and go-between firms such as law firms, accounting firms and corporate innovation centers have arrived one after another Some large corporations- such as Fidelity Investments, etc.- that have in the past considered moving services to Boston, plan to move their headquarters to Boston and also increase their level of investment, and even a gardening organization plans to use fresh flowers and plants to dress up the bridge connecting the city with the Innovation District to obtain more notice from tourists and city residents. The need to satisfy peoples’ needs has brought forth a fervor for construction from city residents and various organizations, and this kind of fervor has itself positively influenced others and carried with it the input of even more strength into the project; all of Boston, with the Innovation District at its core, has dug up a new construction fever.

Menino is in the midst of using a string of “small” actions, using the needs of entrepreneurs to embark upon this effort, thus successfully resolving the “which comes first, the chicken or the egg?” problem that the Innovation District frequently met with in its early start up phases. These methods of his are in actuality also a development and expansion of Boston’s culture and tradition of governance. As Edward Glaeser pointed out in an important article regarding Boston’s development: ” From its earliest years, Boston existed not only as a production center, but even more as a place where people wanted to live: she is a consumption city. As people want to live and work there, whenever the economy met with trouble, residents chose to stand fast and innovate.”

Through the development strategy of the Innovation District, we can also clearly see that a so-called consumption city must start from small matters such as its residents’ clothing, sustenance, living, transportation, etc. needs, and must do its best to create a safe, convenient and livable city environment. Many seemingly trivial and ordinary matters, are actually those that can best cultivate good feelings by city residents for their city and faith in their government, and it is also these ordinary affairs that can encourage city residents to carry out investment and consumption without excessive worry. Moreover, during key and difficult times in a city’s development, a city’s culture and civilized spirit, having been slowly and painstakingly built, will make itself manifest and create enormous power for good.

* * *

Boston’s emphasis on, and attraction to, talent does not only stop at creating a comfortable living environment, nor does it stop at providing employment positions and opportunities to start companies, but also is displayed in the use of innovative science and technology and the products of this. Innovation economist Scott Kirsner long ago wrote about this quality of Boston in his article Innovation City. He believes, that Massachusetts residents quality of both daring to and liking to try new products and new technology has greatly inspired inventors and entrepreneurs to continuously go and create. As innovation and creation have a market here, expended effort can quickly gain acknowledgement and returns. Today, the scope of consumers for innovative products has far surpassed that of individual residents, companies, groups and government, and such consumers long ago already became an important client base.

Through the bio-med, clean energy and computing information technology concentrated in the Innovation District, it can be seen that Boston is an energetic advocate and leading user of many new technologies. Indeed, the Greater Boston Area has eight famous university medical schools, and countless medical organizations. Mass General Hospital, Children’s Hospital Boston, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital are always in the front ranks of American hospital rankings. Mass General Hospital not only ranked number one in the 2011 American Comprehensive Hospital Rankings, but is also Massachusetts’s largest private employer, with 23,000 employees. The Boston area has enormous needs for new pharmaceuticals, new instruments, new apparatus, and new treatment methods. Many clinical medical hospitals and R&D organizations frequently open mutual dialogue and cooperation with companies in related fields, causing the Boston area to become a key center in world pharmaceutical research and development.

Strict standards have been formulated for the Innovation District, requiring that developers do their utmost to use leading environmental friendly and energy conserving science and technology and products, and some companies entering the park have even used technologies that have never been used before. Meandering along Boston’s avenues, high efficiency environmentally friendly and energy conserving BigBelly Solar trash cans can be seen everywhere, produced by a local enterprise. Rental bike stations designed for pedestrian used, called “The Hubway”, have been sensibly placed at transportation junctures. Those who like driving can also enjoy the fast easy car rental service provided by Zipcar.

Last year Boston ranked third on the America’s Greenest Cities ranking, and has been selected as The Best City for Walking in the USA many times, as well as America’s Healthiest City. This green, healthy wave has also touched upon the Innovation District. Computer Information Technology has been widely used in city governance. Graduates of the Harvard Kennedy School working at Boston City Hall have used email to send out introductions to professors excitedly describing the work they’re currently working on; as a daughter project of New Urban Mechanics , we are in the midst of developing a piece of software post haste. After it is successfully developed, all you’ll need to do is to install the software into your cell phone, and once your car begins travelling in the Boston area, we’ll be able to track the rise and fall of your car caused by bumps in the road. After we’ve collected enough information, timely repairs can be carried out to roads affected by such bumps; the large-scale use of information technology will greatly promote the improvement of attention to detail in city management.

The city of Boston is also overflowing with the ideas and fervor of young people, and continuously gives birth to youthful wisdom and inspiration, and I’ll give two examples of this here. The first is, at the end of July, the Pandolfo brothers, for whom the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, held an exhibition, created several huge murals on buildings in the busy city district. One of these murals created a huge public debate, and was called “The Giant of Boston”; this mural has a dimension of 5000 square feet (about 465 square meters), and made an entire building used for ventilation for the Big Dig, located at a busy intersection, into colorful graffiti. This work’s photo was uploaded onto Fox Boston’s Facebook page on August 4th, and the original will be preserved until the end of November for viewing. What is the meaning behind the painting?

City residents can post any of their opinions about the mural on Facebook. Most city residents see it as both a work undertaken for the public good as well as for philanthropy. Some people have praised this work as giving Boston’s streets “color and energy”, giving rise to citizens’ curiosity and imagination. However, many people have connected this painting with 9/11 and terrorism, and not only have expressed their dislike of this, but also suspiciously ask “why did Menino allow them to paint in this place?” Moreover, one of the brothers who created this work, Gustavo, once said, “You should draw whatever you want, and I don’t care whether it’s illegal or not. Cities are just my canvas for painting.” The other brother, Otavia, added, “Surprise is a good thing, it can make life move the human heart.” This completed “illegal” enormous work still stands on the street today, silently accepting the praise and criticism of passerby.

The other example/story is one that occurred to a young Boston resident named Blake Boston. The roots of the incident can be traced back to 6 years ago, when Blake Boston’s adopted mother happened to take a picture of him. In the picture Boston was wearing a baseball cap and collared fur coat, coolly standing in a brave posture, in the hallway of his home. Sixteen year old Boston put this photo on his MSN without much thought, hoping to share it with his friends, and mother and son both thought this was the end of the matter. However, this photo suddenly became greatly popular on the internet two years ago when it was altered by an unknown person to become a meme (meaning a cultural factor that spreads from person to person), and given the name “Scumbag Steve”. In an instant, Blake Boston became the poster-boy of those street kids living fast lives and looking for trouble (doing drugs, drinking alcohol, petty theft, etc.)

Blake Boston’s Facebook page exploded with large amounts of visitors, and the assault on the person of Scumbag Steve continued unabated. He and his adopted mother fell into the depths of previously unknown anxiety and bewilderment, and over the next several days, he chose to stand up for himself, by making online arguments for his innocence , asking for the website(s) to delete the posts, and calling for understanding and respect from web users. However all of this only achieved the opposite effect, only added fuel to the fire. The baseball cap, with small square designs imprinted on it, that he had worn at the time of the picture especially became the tool of internet-users in making their jokes; the first online portrayal showed the cap being worn on the head of ex-Egyptian president Mubarak, and the cap then became a symbol for contrary ideas, and photo-shopped by internet-users onto the heads of the people they didn’t like, with even Obama being unable to avoid such pictures being made of him.

The incident became more serious and more serious as it continued, to the point that Blake Boston was often noticed by people when walking on the street, with people sometimes asking him whether or not he was “Scumbag Steve”. At a loss, Blake Boston finally decided to change his attitude. He decided to accept reality and make “Scumbag Steve” into a brand to sell, and used this opportunity to help himself, as he liked performing rap music, enter the world of entertainment. He ordered limited edition baseball caps and sold them at high prices online, every week produced a rap song with “Scumbag Steve” as its gimmick, and laughed along with all those internet-users who recognized him in real life. Today, he has his own band and manager, and has thoroughly escaped the former money problems he had when he was unemployed and living at home.

Having written to here, I can’t contain my own secret surprise in one matter: doesn’t the city of Boston’s various methods and actions, and the city’s personality that these reflect, completely meet the requirements of Professor Richard Florida’s 3T theory?! Professor Florida has been called a “star professor” in North America. The scope of his research is quite large, and he has conducted intense research into regional economics and public policies, etc. He also is very good at taking his own academic work and making them into public products for business and sale, and it is said that he ranks with Bill Clinton and Bill Gates as famous speech-givers.

Florida’s landmark work is The Rise of the Creative Class, published in 2002. In this book he systematically expounds on the core ideas of how a creative city’s development is formed, these being Technology, Talent, and Tolerance. The ability to attract and serve talent, fostering and using science and technology, and diversity in culture are the basic pillars of creative cities such as San Francisco, New York and Boston. Although more than a few scholars have criticized the logic and rigorousness of Professor Florida’s theory as being clearly inadequate, if the real path trodden by the city of Boston, no matter whether taken as a compilation of experience or as a theoretical guide, is analyzed, these theories of Professor Florida all have extraordinary meaning.

* * *

The construction of the Innovation District and Boston’s rise despite current conditions, have not only provided new experiences for America’s economic development, but have also added a fresh new example for the long-debated problem of developmental trends in post-industrial cities. A group of scholars, including Edward Glaeser, Richard Florida, Bruce Katz and Saskia Sassie, have energetically advocated using innovative economics and smart growth to promote cities’ prosperity and revitalization, in this way thoroughly helping to reverse the problem of city centers declining due to the middle class spreading to the suburbs. During this process, the political and business, academic spheres have maintained unusually close contacts and cooperation.

In America, scholars go through intense, hard work in researching problems, and politicians and entrepreneurs listen to ideas from academia with genuine interest, and courageously undertake real exploration in related theories. Therefore, and due also to the fact that roles and positions in this relationship are often swapped, and the political, business, and academic spheres have formed a reliable, highly efficient mutual and beneficial cycle. Here, study for practical use, and the idea that knowledge and action go hand in hand, are no longer just ideals to pursue, but rather have become an active reality.

Most recently, Professor Florida, wrote an article in The Atlantic Cities, in which he ardently called for re-elected President Obama to place importance on the development of metropolitan areas, and use this to promote economic growth and employment growth: “When we can see the US economy as the combination of cities and metropolitan areas economies, not just as a single national economy, what appears in front of us is a completely different image”. At the end of his article Florida clearly advised,” if we want to return to growth and create jobs, America needs to throw off its national economic policy/strategy as quickly as possible, and should instead place our sights on those many cities and large metropolitan areas that will show us how to emerge from our difficulties.” This is truly very similar in spirit to Menino, in 2008, calling for the two presidential candidates at the time to place more attention on the problems of cities!

Two weeks ago, I specially invited old college classmates who had come to America to take part in training to go have dinner at Anthony’s Pier 4 restaurant in the Innovation District, in the hopes that they could personally experience Boston’s developmental pulse through the Innovation District. This restaurant is a family-operated, specialty restaurant, started by Anthony Athanas in 1963. Since the restaurant’s opening, it has attracted many famous officials and famous people from Massachusetts and even the whole country, and its fame is similar to that of Beijing’s Quanjude restaurant.

Mr. Athanas called for the improvement and transformation of this district in the 1980s. His thoughts at the time were that he wanted to take planning for Pier 4 out of the industrial district and change it to be part of a mixed-use business community, creating many office buildings, residential buildings, parks and restaurants. Mr. Athanas’s dream for this district’s development has finally been realized! However, what he perhaps didn’t expect, is that the restaurant’s current incarnation will be replaced by a one acre waterfront park, and that the soon-to close restaurant run by his descendants has yet to confirm where it will reopen.

After dinner we walked to the balcony in front of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and looked at the sparkling lights of Boston’s center in the night, seemingly both close and yet far away. Looking at the Fine Arts Museum and a few not-distant tall buildings, the future of the Innovation District seemed almost close enough to touch: everywhere you looked were construction sites and expansive open-air parking lots, providing onlookers with material for infinite daydreams.

Innovation District’s planning and start have displayed Menino’s wisdom and resolution, and the fact that Boston, considering how precious its land is, could still have such a large space for its growth, makes it seem that the heavens have blessed and favored Menino! No matter whether Menino’s physical condition does or doesn’t allow him to obtain a 6th term as mayor, and no matter whether the Innovation District is ultimately finished under his watch, the Innovation District has already become the greatest political legacy of Menino’s political career. Perhaps only the Big Dig, completed in 2007, can compare with the Innovation District- which helps in “moving the center to the south [of Boston], [and] developing along the waterfront”- in having such a giant influence on Boston.

Yesterday Brigham and Women’s Hospital held a press conference regarding Menino’s health. He was finally diagnosed with Type II Diabetes, and still needs to be transferred to another hospital for further recovery treatment. Although just a spectator, I still whole-heartedly hope he can return to health soon, win re-election, and finally make the Innovation District into an exemplary work.

I remember that when I worked in Changping, I encouraged cadres to read a report entitled Grass of the Sun-Standout Female Entrepreneur Shi Jingxian’s Legend, and during this time I also went multiple times to see the bedridden Shi Jingxian herself. The reason I esteemed her so greatly is because while working in Changping she did two things. One was setting up one of China’s famous light industries at the time–the Beijing Baowenping (Thermos Bottle) Factory. The second is that she advocated restoring the Ming tombs and other cultural relics and opening them up to tourists.

I have always believed, that it is very difficult for a person to successfully and truly complete one or two accomplishments in their life, and that in order to get the opportunity to complete such an accomplishment, we have to spend long hours in preparation and waiting. Shi Jingxian was fortunate because she didn’t lose the opportunity to complete these tasks, and thus lived a life without regrets! I hope that fortune also likewise smiles on Menino! Having been abroad for two years, I don’t know how Mrs. Shi has been doing recently, and so would truly like to wish her: Good peace, health and happiness to such an outstanding person.

To thank all you readers in your patience for finishing this article, I’ve provided “Scumbag Steve’s” first song for your listening pleasure.

A Chinese version of the article can be found at Sina Financial and Economics Blog.