Introductory Essay

When I first saw For the Love of God and His Prophet: Religion, Literature, and the Arts in Muslim Cultures on the spring course website, I was extremely excited. After living in Morocco all summer, I had become quite interested in Islam. I had looked for a class on Islam that fall, but I had not found one that fit into my schedule or met any general education requirements. I was behind on meeting my Gen Ed requirements, so I had to take at least three Gen Ed courses this year. Not only did Culture and Belief 12 give me a Gen Ed and an introduction to Islam, but it also appeased my creative side and my love of art. I am an extremely visual person and that side of my brain has not gotten enough attention in my life. I never took an art class or delved into any visual art extracurricular in high school or college. Yet I have always noticed about myself that I remember things more when I engage visually and experientially. I loved the idea of the class on paper and I hoped it would meet my expectations.

The reason why I first became interested in Islam was because of Morocco. I went to Morocco for the first time with my grandma when I was 15. Before that point, I had never known a single Muslim personally. In just the week that I was there, I met so many Muslim people and I enjoyed learning about their culture and their values. I was incredibly struck by the beauty of the art, architecture, and the Arabic language. I loved looking at the beautiful squiggly lines on the signs and on my coke bottle. I longed to learn what they meant.

My senior year when I learned that my high school was offering an introductory Arabic class, I signed up immediately. In a short semester I learned the Arabic script and many conversational and introductory words. I absolutely loved every minute of it. My Arabic teacher would always play popular music from the Arab world at the end of every class and I always looked forward to that. Although I still knew very little about Islam, what I knew about the language and culture enthralled me.

The next year at Harvard, I wasn’t sure if I would continue to take Arabic, but I had to meet the language requirement so I decided to take it anyway. I continued to enjoy it and I decided to go back to Morocco that summer to study at the Arabic Language Institute in Fez. This was when my real interest in Islam began. Over the summer, I made many close friends who were serious Muslims. I learned more about what the Qur’an says from what my Muslim friends said. I started to think deeply about Islam and question all of my preconceived notions. The topics that particularly interested me were those that concerned women and the hijab, and I often got into lengthy conversations with other students and my Moroccan friends about the hijab, virginity, marriage, and the role of women in Moroccan culture. So after being immersed in an Islamic society for an entire summer, I longed to learn more about what I had witnessed over the summer, and I found the perfect class in which I could do that.

Over the course of this class, I have created six creative responses to the readings we have done that also encapsulate many of the themes that interest me. I have created artistic pieces using many different combinations of mediums, such as knitting, photography, colored pencil, watercolors, collage, and paint. It has been a wonderful experience being able to represent my ideas visually and make a statement that reflects my thoughts and feelings on certain issues. I have learned that sometimes it is much easier to demonstrate ideas through pictures than through words. After this class, the saying, “A picture is worth more than a thousand words” has taken on a new meaning for me. Art is almost its own language, and it is something that can be interpreted universally. You don’t need to understand Arabic to comprehend the beauty of Arabic calligraphy or the Qur’an when it is recited with perfect tajweed. You don’t have to understand Hafez’s wordplay and metaphors to appreciate the beauty of his imagery. So many works of Islamic art don’t need any explanation in order to grasp the magnitude of their beauty and the power of their message.

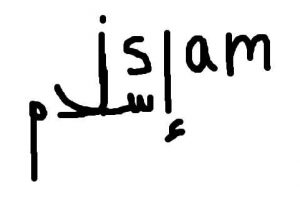

On the first day of class, hearing Professor Asani talk about some of the issues that had really concerned me over the summer, and after reading The Infidel of Love, I knew I was definitely taking the class. I was really struck by the idea that Islam and America have much of the same ideals, as Professor Asani stressed that day and I would come to learn for myself throughout the course. While sitting in lecture that first week, an image came to my mind and I knew I had to use it in a creative response. The image was of the word “Islam” written in English and Arabic script yet interconnected so that you could read it from left to right and see Islam, and read it from right to left and see the same word written in Arabic script. I particularly liked this idea because it seemed to highlight the fact that even though the Qur’an is only the word of God when written in Arabic, Islam itself is a universal concept that can be understood anywhere and in any language.

One other excellent aspect of this class was the outside opportunities it provided to learn more about Islam experientially. One of the opportunities I was able to participate in was the Comic Book Workshop that was offered at the CMES. That was a really cool experience that taught me a lot about juxtaposition in works of art and about interpreting images and symbols in new ways. One activity we did was look at a word in Arabic such as the word for freedom, tahrir, when it is stretched across the boxes of a comic. We were asked what new meaning we could pick up just from looking at the shape of the letters and how they were placed. To me, it looked like an arm was reaching for something it had lost, trying to reclaim it. We talked about the importance of the “gutter” in making comics and how the empty space between the pictures provides the reader with room to use their own imagination and make their own interpretations about what happens between the pictures. I tried to employ the tools we learned in that workshop to make my own comic depicting the words in the Qur’an about the light of the prophet that are so important to Islamic mysticism.

In my third artistic response before spring break, I decided to incorporate my ideas on the hijab with the idea of crying, which we had talked a lot about and had learned is important when reading, reciting, or listening to the Qur’an, the poems of Hafez and other notable Islamic poets, and the taziyeh in Iranian theatre. Crying is particularly important because it creates a deep emotional connection between a person and God, and it shows that the person is moved on a deeply spiritual level. Crying and wearing the hijab are both signs of piety that are highly external: they demonstrate one’s faith to others. While they can be real signifiers of piety, that can also easily be put on and replicated by someone who is not so religious. This creates an important struggle in Muslim societies that use the hijab as a symbol of Muslim identity. If a person wants to maintain their Muslim identity and be considered more religious, they will gain status in a highly religious community by covering up more. Conversely, this could be said of Western cultures as well, particularly regarding women who wear a great deal of make-up and expose a lot of skin in order to gain status in their communities. Of course these women aren’t doing this for religious reasons, but that is because the societies they live in and/or the families in which they were raised did not emphasize religion. Instead, they were taught that women who show skin and look beautiful are able to attain a higher social status. People often try to say that putting on make-up is just another form of wearing a hijab, and this is true from a superficial level. In both cases, the females in question are hiding their true selves from men and are gaining acceptance/status in their respective cultures. However, these peripheral cues are just that: external. They say nothing about the beauty or true religious nature of the soul. Of course, there are many women who wear the hijab for the right religious reasons, not just to put up appearances and appease people, but because they truly believe it is the morally right thing to do. In my creative response, I was trying to demonstrate that crying and wearing a hijab are similar in their meaning and importance to Islamic cultures.

Continuing on the theme of superficiality, I decided to interpret the book The Conference of the Birds with a fashion shoot. I collaborated with my friend Theresa Tharakan on this project, and together we planned, photographed, modeled, and edited pictures of all ten birds that make excuses to hoopoe for why they do not want to go on a quest to find the Simorgh. We thought that fashion would best represent how the birds should be interpreted in our culture today, because like the birds, fashion is a vain, superficial activity that delves away from spirituality and piety. We worked hard to construct a certain recognizable persona for all of the birds in our photographs and put them together in one compiled image to demonstrate how they relate to one another.

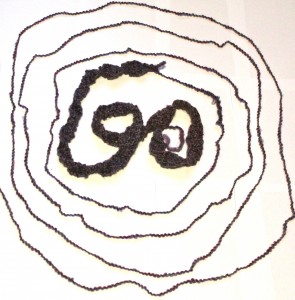

My next response was an image that again came to me while I was sitting in lecture. We had been talking about dervishes and how when they spin, their skirt creates an endless circle that spiral around them. Immediately this spiral image came to my mind, and as I learned more about Sufism, I learned the importance of being close with God and how using a personal pronoun instead of God’s name, demonstrates that bond. I started to think of my image as the layers that a Sufi has to go through in order to obtain true knowledge and understanding of God. I decided to use the medium of knitting because it is a repetitive and almost spiritual task that is monotonous yet relaxing. It reminds me of the action of using prayer beads and repeating the shahada over and over again. Also the action of knitting is interconnecting yarn, which could be a metaphor for the interconnectedness of Sufis with God.

My last artistic response was a two-part response to Persepolis. I decided to respond particularly to the image of the girl who has a veil and an Islamic arabesque on one side of her head, and is uncovered with tools of knowledge on the other side of her head. This image represents a dichotomy between religion and secularism in her mind. I particularly relate to this image because I often feel I have a dichotomy between my Jewish heritage and my interest in the Middle East and Islam. I tried to convey this in a similar image to the one in the book. The second part of my response, however, is an image that takes the symbols of the three big religions and attaches them by a heart with the backdrop of the American flag. This represents what I have learned in this class: that America is a place that upholds the ideals of all three of these religions, and these three religions are united by their love for humanity, the worlds, and for God.