Introduction

ø

This seminar was easily the most meaningful part of my freshman fall, and one of the most exciting classroom experiences I’ve had. I emerged from the Barker Center every Tuesday night feeling energized and invigorated, my mind whirring as I tried to process all that I had just learned. I went into this class very interested in Islam and its intersection with politics and gender issues, but I knew little about the religion and I had never been exposed to Muslim literature. I enjoyed the wide range of literature we read over the course of the semester, from feminist Urdu poetry to epics like The Journey of Ibn Fattouma. Each week’s readings introduced new cultural perspectives and nuances to our exploration of Islam. It was frustrating to have my attempts to synthesize and generalize thwarted, but exciting to realize that there is such diversity within Islam that generalization is not possible.

Professor Asani’s presentations in class reinforced this realization, and taught me so much about Islam, both in terms of theology and questions of religious authority, and also in terms of the intersection of religion with political and social issues such as women’s rights, conflicts between Islam and the West, race and class divisions, and the emergence of the Muslim nation-state. I enjoyed diving into the complexity of religious authority in Islam, from the tensions between spiritual and scholarly figures, to the role of ulama in doctrinal interpretation, to the influence of poets. Listening to Muslim music and looking at artwork added another interesting dimension to the class and our cultural studies. And it was incredible to be surrounded by students with similar interests but diverse backgrounds, who brought unique perspectives and interpretations into every discussion. I learned so much about the world from my classmates, such as the reality of life in Pakistan from Zunaira, Orthodox Jewish practices from Julia, approaches to Catholicism and morality from Ashley, and the complex nature of split identities from many who had grown up in more than one country.

Over the course of the semester, my religious and cultural literacy improved dramatically. I quickly realized in the first few weeks how religiously illiterate I was – not just about Islam, but about any major religion (I grew up in an atheist household and I have never read the Bible). It was exciting to feel like I had learned so much and my perspective had been substantially widened over the course of just two and a half hours. The course exposed me to the richness and depth of religious and cultural studies of Islam, but also highlighted how much I do not know and the importance of acknowledging that. I learned the importance of being open to people and perspectives that do not fit into my preconceived notions. In today’s world, outsiders (particularly Westerners) have a harmful tendency to generalize and stereotype Islam, treating it as an easily definable practice, or a being with agency that is responsible for all of the actions of its followers. When we generalize about a religion, particularly about its relation to extremism and violence (as has been seen in recent reactions to ISIS), we create dangerous and unnecessary culture wars, and risk dismissing or alienating people who do not fit our idea of what a Muslim looks like. We give too much weight to religion when we blame terrorism or sexism or political events on Islam, ignoring the historical, cultural, and political factors at play. Generalizations have only served to perpetuate misunderstandings and exacerbate divides.

Perhaps the most important thing I learned from this seminar is that Islam is a religion, not a person. As Professor Asani reiterated several times, Islam does not do things; people do. And it is important to examine and strive to understand these people’s motivations apart from religion by using a cultural studies approach. The cultural studies approach entails looking at historical contexts, cultural and political influences and power dynamics, social divisions such as race and class, and personal motivations when analyzing events or movements. I will strive to apply this approach in my future studies.

However, while it important not to generalize, it is possible to analyze and discuss common themes that emerged throughout the class. While the literature we read portrayed diverse and often quite different cultures, there was much overlap in terms of issues the texts grappled with, and these commonalities emerged in my portfolio as well.

One such commonality was the importance of poetry as a means of expression and source of authority. We looked at quite different forms of poetry, from Urdu na’ts to the feminist poetry of the “We Sinful Women” collection, to Iqbal’s “Complaint” and “Answer.” Despite the differences in style and substance between these poems, all conferred the poet with religious and cultural authority, as poetry is widely respected in Muslim tradition. I tried to reflect this in my portfolio by writing poems for two of my pieces. For one, I imitated the form of Udru na’ts to write an ode to poetry itself, and for the second, I wrote a poem about the policing of women’s bodies in Madras on Rainy Days. This poem ended up seeming sort of reminiscent of “We Sinful Women,” since it deals with gender issues and feminist thought.

The oppression of women is another theme I focus on in this portfolio that came up often in class discussions. The relationship between Islam and gender is complex, as many countries calling themselves Muslim nations have a history of oppressing women, leading many outsiders to associate Islam with patriarchy. While it is true that religious interpretations have played a role in perpetuating patriarchy, it is important to use the cultural studies approach to analyze other influences at work, namely power dynamics, emerging political movements, and cultural practices that predate Islam. Women’s bodies seem to have become the battleground for conflicts between Islam and the West, as conservative and extremist regimes have subjugated women as a means of reaffirming their brand of Islam and garnering political support (an example of motivations being political rather than religious).

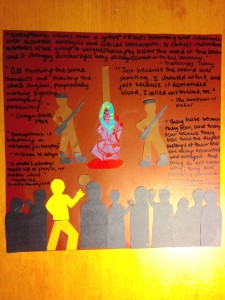

Many of works of literature we read, such as “We Sinful Women,” Persepolis, The Swallows of Kabul, and Madras on Rainy Days tackle gender issues, and as a feminist, I found this theme to be particularly interesting. It was often painful to read certain passages in these works, such as the stoning scene from The Swallows of Kabul, in which women were brutalized or subjected to horrible injustices. Our class discussions on the subject were as engaging as they were depressing, as it became surprisingly easy to relate these injustices to our own experiences with rape culture on campus or slut-shaming or relatives’ reactions to girls liking boys. Several of my portfolio pieces center around the oppression of women: my collage interpretation of “We Sinful Women” focused on women’s bodies and their simultaneous power and powerlessness, my poem based on Madras on Rainy Days similarly broached the theme of women surrendering control of their bodies, and my re-telling of The Wedding of Zein played with giving a voice to a girl who is rendered voiceless by her society. Through these pieces, I tried to challenge narratives or manifestations of patriarchy presented in the literature.

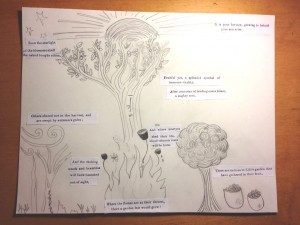

Another issue that is prevalent throughout the works and my portfolio is the conflict between progress and tradition, a conflict that often unfortunately gets conflated with the conflict between Islam and the West. This was the central theme in Ambiguous Adventure, as village leaders struggled over the decision to send Sambo Diallo to receive a Western education rather than the traditional training centering around Islam and spirituality. This eventually became a conflict between symbols of Western advancement, such as modern innovations and material wealth, and the effort to hold on to village tradition, religious observance, and spiritual meaning. I depicted this fight in my marker drawing entitled “Progress v. Tradition,” in which a boot representing Europe is crushing Africa and Sambo Diallo’s village. “The Garden,” a piece based on Iqbal’s “Complaint” and “Answer,” also explores this theme. Iqbal argues in his “Answer” that a commitment to progress is a central component of Islam, since Muslim societies have historically been leaders in innovation, science, and the arts. He says that while the West has taken over this role, Muslims must reaffirm their faith and efforts to advance their societies, so that “after centuries of tending soars Islam, a mighty tree.”

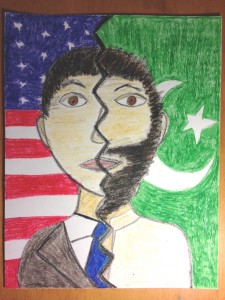

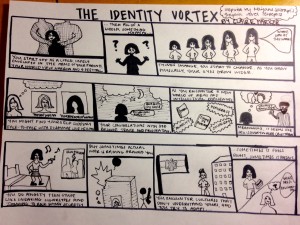

The nature of identity is also a critical question raised by the texts and my artwork. The 20th and 21st centuries have been critical periods for Muslim identity, as Muslims have grappled with religious and cultural identity in the midst of emerging Islamist movements, extremism and Western backlash, global conflict, and avant-garde religious interpretations such as Islamic feminism that have all attempted to define what it means to be a modern-day Muslim. I took on the idea of developing a multifaceted personal identity in my comic “The Identity Vortex,” based off of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, which portrays the evolution of Satrapi’s own identity amidst the turmoil of the Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq war. My piece “Split Identity,” inspired by The Reluctant Fundamentalist explores the division of identity that Muslim immigrants to the West often experience as they struggle to reconcile two often-opposing backgrounds.

These themes are critical today, as the world is becoming increasingly polarized between the West and predominantly Muslim regions and movements. ISIS is killing Westerners and spouting hate, and the West is perpetuating Islamophobia with equal measure. In the process, large groups of people across the globe are being otherized, their identities called into question or overlooked as extreme stereotypes take center stage.

In such a world, knowledge of the complex realities of Islam and Muslim societies is critical as a means of countering this trend, and this seminar has equipped me with a baseline of such knowledge (although I will always keep in mind how much more there is to discover). I will apply this knowledge to my consumption of news and my approach to analyzing the politics and current events of predominantly Muslim countries. I’m planning to study Government, and after this class, I plan to continue to explore the intersection of Islam and politics, as well as relations between the MENA region and the West. And five years from now, I will remember sitting around that wood table in the Barker Center, and the lessons that emerged from those Tuesday night discussions over dried mangoes: the importance of being open-minded, allowing complexity to triumph over generalizations, and owning up to my own ignorance.