Looking Hard at the Commons

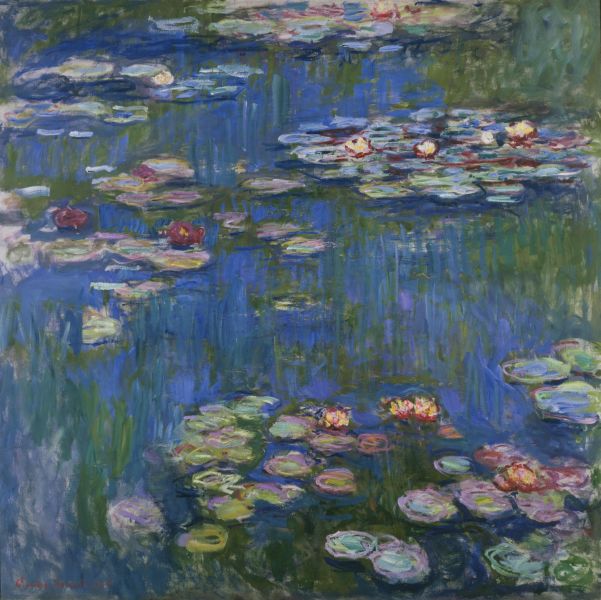

Defining the commons is hard – like a painting, the longer you look at it, the less clear it seems to become. Now we can identify a few key features of the commons that pretty much all authors agree on: a commons is a resource that is freely available to a certain population. A public park is a good example of this sort of commons. But a commons need not be free like free beer. Some commons cost money to enter and use – it’s just that the cost of entry is imposed neutrally (no one can be given special access; no one can be denied). A public bus is a good example of that sort of commons.

So far, so good. But once we try to add more detail to our definition of the commons, things get contentious. Let me just point out a few examples:

- We said a commons is a resource. But what’s a resource? The stuff of physical property is definitely a resource. The stuff of intellectual property – patents, copyrights, designs and codes – are probably resources as well. But what about things like standards of practice, languages, and social norms? Is English really a commons? Is social etiquette? Different authors disagree.

- We said a commons is freely available. But when is something freely available? If a fee is imposed neutrally, but is prohibitively high for most people, is the resource still a commons? If the resource is not modular, transferable or interoperable, is it really a commons? Again, different authors disagree.

- We said a commons exists for a certain population. But of course, what is a population? Is a resource a commons if it only available to two people? What about 200? What about the whole of society?

Now the world doesn’t necessarily need one fixed and perfect definition of the commons. People can disagree about what constitutes a relevant population or resource, or what we really mean by freedom. But here at the ICP we need a clear definition of the commons in order to identify instances of it in the biotech, alternative energy, and educational material industries. Here are a few of the questions we’re trying to answer for ourselves before we can begin developing our field methodology:

- Does a commons have to be self-governed? Many are. Public libraries are used by the taxpayers that fund and sustain them. But many aren’t. The Internet Protocol might be a commons, but few Internet users have a say in its design and operation.

- Does a commons require predictable access? Again, many are, but many aren’t. FEMA might once have been considered a public resource. But since Hurricane Katrina, when huge populations had no predictable access to emergency relief, FEMA’s status as a commons has been less clear.

- Does a commons require that people know it’s a commons? If no one knows that a park is public, is it really a public park?

If all this becomes a little abstract and theoretical, well, it is. But over the next few weeks we’ll be working hard to clear up the theory so that we can quickly put it into practice and identify commons-based practices in our areas of study.

Explore posts in the same categories: Uncategorized, Weekly Updates

February 19th, 2009 at 8:18 pm

The parameters that Yochai Benkler uses to typify the commons are amount of openness and amount of regulation. This allows us to conceptualize a range of institutional forms that meet the definition of the commons. The complexity that this adds to the commons definition is worth the effort since the result provides us with a reason why peer production is merely a subset of commons based production. It is only through a decentralized and individually driven effort that peer production exists.

March 23rd, 2009 at 10:04 pm

It occurs to me that another relevant question is: from where do the resources of the commons spring, and how often / robustly are they renewed?

I don’t have a hard and fast answer, but Ican imagine “commons” regularly used by much broader populations than contribute substantially to their substance or “upkeep”, and it seems that this difference might be quite relevant.