Celebrating Fair Use in Films

by Krista Cox

This year, Fair Use/Fair Dealing Week immediately follows the Oscars and I definitely have movies on my mind. The Green Book (which I haven’t seen yet) was one of the nominees—and ultimately winner—of the coveted Best Picture Award, but was not without its share of critics. Like other movies dealing with race, critics said that it minimized the true extent of racism and fell into the “White Savior” trope. Just before the Academy Awards, comedian Seth Meyers released a video highlighting these criticisms parodying popular films, including Hidden Figures, The Blind Side, and The Help. Meyer’s White Savior: The Movie Trailer is a fantastic example of parody which, of course, is protected by fair use. Since Kenny Crews covered parody so well in his Day 1 post, I’ll turn to a different aspect of fair use and movies.

Although films obviously create their own creative content, protectable by copyright, often these works incorporate existing content. Depending on the particular use, a filmmaker or production studio may choose to license a particular copyrighted work, but in other instances the film creator has relied on fair use. Here are some examples where fair use and films have gone hand-in-hand—both in the documentary film context as well as feature films and shows.

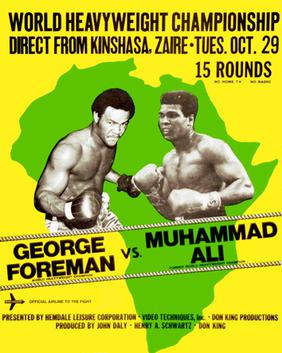

Documentary filmmakers have relied heavily on the doctrine of fair use, which makes a lot of sense. If documentary filmmakers constantly had to rely on permission and licenses—which would also mean that a rightholder could refuse to grant permission—the result could be that these documentaries lacked proper historical references and context. In a 1996 case, the Southern District of New York refused to grant Turner Broadcasting’s motion for injunctive relief, finding that the clips of a boxing match film involving Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in a documentary about Muhammad Ali was likely a fair use. In Monster Communications, Inc. v. Turner Broadcasting Systems, the court noted that only a small portion of the total film—just 41 seconds—was taken and that the documentary used it for informational purposes.

Documentary filmmakers have relied heavily on the doctrine of fair use, which makes a lot of sense. If documentary filmmakers constantly had to rely on permission and licenses—which would also mean that a rightholder could refuse to grant permission—the result could be that these documentaries lacked proper historical references and context. In a 1996 case, the Southern District of New York refused to grant Turner Broadcasting’s motion for injunctive relief, finding that the clips of a boxing match film involving Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in a documentary about Muhammad Ali was likely a fair use. In Monster Communications, Inc. v. Turner Broadcasting Systems, the court noted that only a small portion of the total film—just 41 seconds—was taken and that the documentary used it for informational purposes.

In another instance of documentary filmmaking, artist Bouchat sued over the use of the Baltimore Ravens’ logo in several videos. While a prior case held that the Baltimore Ravens had infringed the logo design by Bouchat for several years, the use in the films (and historical exhibits) was considered fair. The Fourth Circuit held in Bouchat v. Baltimore Ravens that the videos at issue used the copyrighted material in a transformative way, telling the history of the Baltimore Ravens and the logos were “fleeting” in nature.

And in yet another litigated case over a documentary film, National Center for Jewish Film v. Riverside Films, a district court noted that the use of film clips in Sholem Aleichem: Laughing in Darkness (about the life of a 19th century Yiddish author) was transformative because it incorporated various clips with scholarly commentary (NB: whether the films had entered the public domain was also questioned, a factor that the court weighed in favor of fair use). Again, because these clips were used in a transformative way that did not supplant the market for the original film, the court held the use to be fair.

Not every fair use ends up being litigated, though. Indeed, most documentary movies probably don’t involve rightsholders claiming copyright infringement in part, thanks to the Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use. That Code of Best Practices, like other Codes (see: Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Academic and Research Libraries or the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Software Preservation—two best practice statements released by ARL), relies on the consensus view of fair use best practices in the community for which it was written. The 2005 Code for Documentary Filmmakers has had a tremendous impact on the community, making it easier for filmmakers to get insurance, avoiding unnecessary licensing costs and leading to the release of films that may never have been finished otherwise. One of the successes is This Film Is Not Yet Rated about the MPAA’s rating system. While the director had initially planned to license the clips used, those licenses would have prevented him from using the material in a way that criticized the entertainment industry.

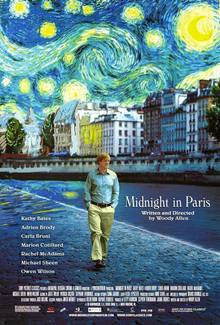

While the documentary filmmaker community relies heavily on fair use there are a number of examples where fair use was invoked in feature films, as well. For example, the Oscar-winning movie Midnight in Paris, about a screenwriter, played by Owen Wilson, who travels back in time to the 1920s and hangs out with luminaries like Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Cole Porter, Salvador Dali and others was the subject of a lawsuit.

|

|

In one scene, the main character paraphrases a line from novelist William Faulkner’s novel, Requiem for a Nun (the line in question is, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past”) and provided attribution back to Faulkner. Nonetheless, the Faulkner estate sued, claiming that the use of the line infringed copyright. The Northern District Court of Mississippi referenced de minimis usage (discussed a bit more below), but also conducted a full fair use analysis finding that the quote was of “miniscule” importance to Faulkner’s novel as a whole and the use in Midnight in Paris, which amounted to a mere 8 seconds of the feature-film, did not harm Faulkner’s market for his novel. To the contrary, the court questioned: “How Hollywood’s flattering and artful use of literary allusion is a point of litigation, not celebration, is beyond this court’s comprehension. The court, in its appreciation for both William Faulkner as well as the homage paid him in Woody Allen’s film, is more likely to suppose that the film indeed helped the plaintiff and the market value of Requiem if it had any effect at all.”

Similarly, in the 2013 film Lovelace, based on the biography of Linda Lovelace, an actress who starred in a famous pornographic film but later became a spokesperson against pornography, the producers re-created three scenes from Deep Throat. The Southern District of New York in Arrow Productions v. The Weinstein Company ruled the use transformative because it provided “new, critical perspective” on Lovelace and would not supplant the market for the pornographic film.

Courts have considered and upheld fair uses in the film context, but some have found in favor of the defendant without even needing to go through the four fair use factors. Instead, for various uses of copyrighted works in TV shows and feature films, some courts have found in favor of the use on the basis of fair use’s cousin, de minimis use. In these de minimis use cases, courts have determined that the amount used was so small and trivial, the court need not engage in a full fair use analysis. These cases have included, for example, the 2000 rom-com What Women Want, featuring Mel Gibson (involving the depiction of a pinball machine in the background); the 1995 crime thriller SE7EN, featuring Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman (use of copyrighted photos appeared fleetingly and out of focus); and HBO’s TV series Vinyl which was created by Mick Jagger and Martin Scorsese about a record executive in the 1970s (fleeting use of a dumpster tagged with graffiti in the background of a single scene).

Krista L. Cox is the Director of Public Policy Initiatives for the Association of Research Libraries (ARL), in Washington D.C. Prior to joining ARL, Cox was the staff attorney/legal counsel at Knowledge Ecology International, a nonprofit organization that searches for better outcomes, including new solutions, to the management of knowledge resources. She may be reached at krista@arl.org or on Twitter: @ARLpolicy