Fair Use and Video Streaming

By Carla Myers

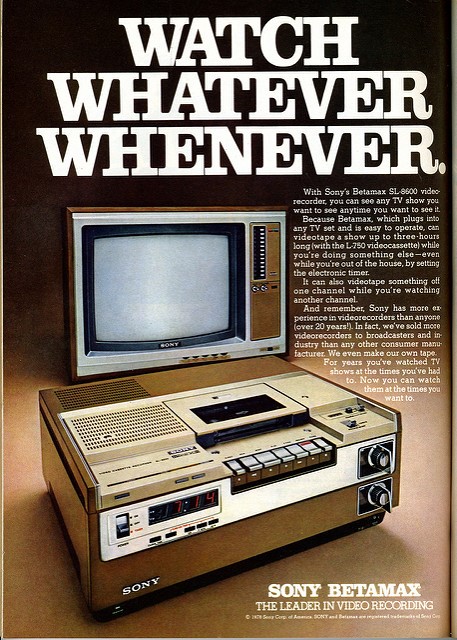

The use of video as a part of course instruction is certainly nothing new. However, I would argue that the ways in which instructors and students desire to engage with video has changed substantially over the years. Twenty years ago, when I was an undergraduate student, if a video was used as part of course instruction, we watched it one of two ways: 1) the instructor set aside time during a class for us to view the film, or 2) we borrowed the library’s copy that had been placed on reserve and watched it in preparation for class discussion. Legally speaking, these two options for watching the film did not raise any significant issues. The performance of the film in class was covered under the face-to-face teaching exception found in Section 110(1) of U.S. copyright law and the circulation of a copy via the library’s print reserve service was covered under the first sale doctrine found in Section 109. I gave little thought to these laws and methods of delivery when I was a student.

How times have changed. Now, as a copyright professional, helping instructors and students lawfully access video is something that I give a lot of time, thought, and analysis. In fact, for much of the past decade, I have worked in this field overseeing library reserve services. And in that time, while the options available under Sections 110(1) and 109 are still available to the students and instructors, most patrons now prefer to engage with video in a streaming format, and the legal exceptions available for filling these requests are not as clear.

When it comes to film streaming, libraries and educational institutions can consider the Technology, Education and Copyright Harmonization (TEACH) Act, found in Section 110(2) of U.S. copyright law and the fair use exception found in Section 107.

The TEACH Act was passed in 2002 in an effort to address the challenges being presented as online education began to emerge as one of the primary ways of delivering content to students. The intent was to be able to replicate, online, the same rights that an instructor or student might have in the classroom under Section 110. If you can meet all of the points of compliance required by the law, the TEACH Act it does provide options for streaming video online for course instruction. The problem libraries and educational institutions have with the TEACH Act is that it requires a tremendous amount of collaboration and effort from individuals and departments across campus to ensure that the 15+ requirements found in the statute are consistently being met for each film that instructors stream to their students. The TEACH Act also places a variety of limits on how works can be used and the period of time they can be made available to students. As such, many libraries and educational institutions interested in streaming film are looking to a much more flexible standard, fair use When making fair use determinations, we look to the fair use statute in Section 107. This statute states that “[n]otwithstanding” the copyright in the materials “the fair use of a copyrighted work…for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research” is not an infringement of copyright, subject to the four factors outlined in Section 107:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Let’s review how these factors interplay with the streaming use case.

Factor 1: Purpose

When it comes to streaming video, the first factor, the purpose of the use, will almost always weigh in the library’s favor when the film is being made available for educational purposes that support the teaching and learning mission of the institution. Here, the more transformative the use is the better. In his article, Towards a Fair Use Standard[1] Justice Pierre Leval tells us that a transformative use is one that “employ[s] the quoted matter in a different manner or for a different purpose from the original” and that “adds value to the original” through the “creation of new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings” (p. 1111). Film can definitely be used in a transformative way! For example, World War Z is a summer blockbuster that follows a man and woman as they try to determine what has caused the zombification of much of the world. This movie could be appreciated as a form of entertainment by anyone, but what if the film was used by an instructor teaching a class called “Introduction to Emergency Management?” What if the instructor asked her students to watch the film and, based upon what they learned in the class, provide criticism and commentary on the response of first responders, the government, and the military to a zombie/health crisis? This brings the viewing of the film into an entirely different context – scholarly -and students will apply new insights and provide greater understanding to the film, adding value to their educational experience in the course.

Factor 2: Nature

The second factor, that looks at the nature of the work being used, will more likely support streaming of factual-based films, such as documentaries. However, this does not mean that popular films cannot be streamed if they are being used as part of course instruction (see the example above), especially since popular films and other creative media are often utilized under a fair use standard.

Factor 3: Amount

The third factor asks us to consider the amount of the original work that is being used. This can be one of the trickier factors to evaluate, but mainly because so many misconceptions surrounding this factor exist.

For example, many people have heard that you can use up to 10% of a work or, in the case of film, up to three minutes, and that will qualify as fair use. Under the law, the fair use statute places no such limits on the amount of a work that can be used, nor does it abide by any arbitrary limits. There is definitely no magic number or timed amount that will provide an institution with any type of safe harbor to shield them from claims of infringement. If we take a look at the judicial history of fair use, we will find numerous cases where the courts have found that the reuse of 100% of a work to be fair, and others where the reuse of small portions of a work have been found to be infringing.

Frequently instructors will want to provide students with access to an entire film, and that may be supported under the third factor if the entire work is important to achieving the educational objectives of the course. Judge Leval tells us that when considering the third factor, “an important inquiry is whether the selection and quantity of the material taken are reasonable in relation to the purported justification” (1990, 1124). For example, say an instructor is teaching a computer generated imagery (CGI) course and wishes students to view the film The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring directed by Peter Jackson (2001) to show what groundbreaking use of CGI looks like in film. While the film contains many scenes that are rendered almost completely in CGI (the actor playing Gollum included!), there are also many scenes in the film that contain no CGI. For this course, the instructor could likely tailor the course to student-viewable clips from the films featuring CGI focused scenes. However, if an instructor was teaching a class called “Tolkien in Theater, Radio, and Film” that explored how Tolkien’s works have been retold in these media formats, it may be appropriate for students to have access to the entire film so they can compare Peter Jackson’s expression of the story against other versions.

Factor 4: Market

Over the past decade, the fourth factor of fair use has become more complicated to address when looking to stream film as part of course instruction. This is because of the expansion of the commercial streaming market that includes library vendor services (e.g., Hoopla and Kanopy) as well as general vendors such as Amazon, Hulu, iTunes, Vudu, and Netflix. These services offer the public access to streaming film through rental, licensing (read the terms with these vendors…rarely do we purchase digital files from them anymore), or subscription models.

When a film an instructor is interested in making a work available to students in its entirety, and the work is available through one of these vendors, we must take the streaming licensing options into consideration when evaluating the potential market effect of the use. As with all fair use determinations, the existence of a license for rental or “purchase” of a work does not mean that fair use can’t be used. But it does mean we have to work through our decision-making process on this factor more carefully. The argument for fair use can be strengthened when a film is not commercially available in a streaming format or when an instructor only requests clips – because, in these examples, there may be limited market harm.

Enter the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Academic and Research Libraries (2012) put forward by the Association of Research Libraries, the Center for Social Media at American University, and the Program on Information Justice and Intellectual Property at the Washington College of Law, American University. This Code, part of the family of fair use best practices codes,[2] can help librarians and educators is addressing these considerations and making thoughtful determinations of fair use.

The Code tells us that a fair use argument can be made for making “appropriately tailored course-related content available to enrolled students via digital networks” (p. 14). Here, it’s important to remember that fair use determinations must be made on a case-by-case basis. This statement in the Code does not mean that making any course-related content available to students online is a fair use, each title must be evaluated for fair use based upon the facts specific to its use in the course and its market availability. The Code does provide us with some enhancements that can aid in the making of these decisions. They include:

- An argument for fair use can be strengthened when the film is being used in a transformative context and the amount being used is appropriate to the instructor’s pedagogical goals (p. 15).

- Fair use arguments are reviewed on a regular basis to help ensure the works being used and the amount of the film being made available remains relevant and appropriate for course instruction (p. 15).

The Code also provides some additional factors to consider in these situations:

- “The availability of materials should be coextensive with the duration of the course or other time-limited use (e.g., a research project) for which they have been made available at an instructor’s direction.

- Only eligible students and other qualified persons (e.g., professors’ graduate assistants) should have access to materials.

- Materials should be made available only when, and only to the extent that, there is a clear articulable nexus between the instructor’s pedagogical purpose and the kind and amount of content involved.

- Libraries should provide instructors with useful information about the nature and the scope of fair use, in order to help them make informed requests.

- When appropriate, the number of students with simultaneous access to online materials may be limited.

- Students should also be given information about their rights and responsibilities regarding their own use of course materials.

- Full attribution, in a form satisfactory to scholars in the field, should be provided for each work included or excerpted” (p. 14).

Those familiar with the TEACH Act will see some of its requirements echoed in these recommendations! While fair use and the TEACH Act are two separate statutes, it is not unreasonable to consider how some of TEACH’s requirements, like limiting access to online educational resources to those enrolled in the course and providing information on copyright law to instructors and students, can help support the application of fair use in these situations. When it comes to streaming film, there are also considerations under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (often referred to as the DMCA) of which we must be aware. This goes a bit beyond the scope of this blog post, but there are good blog posts on this out there that explore these considerations, and it is a topic that has been addressed repeatedly as part of the triennial rulemaking process administered by the Librarian of Congress.

While licensing access to film for instructional use is an option for libraries and educational institutions to consider, we should be careful not to view it as the only option available to us. We can’t forget our mission as libraries and educators to provide access to quality resources that enhance students educational experience. Congress recognized the importance of the work we do when including exceptions like fair use in the law. Fair use arguments can be made for providing students with access to streaming film. As in the case with all fair use determinations, they just need to be made thoughtfully, and demonstrate a balancing of the four factors in a way that reflects both the rights of users and those of rightsholders.

Carla Myers is Assistant Professor and Coordinator of Scholarly Communications for the Miami University Libraries. Her professional presentations and publications focus on fair use, copyright in the classroom, and library copyright issues. She has a B.S. in Psychology from the University of Akron and a Masters in Library and Information Science from Kent State University. Her new book, Copyright and Course Reserves: Legal Issues and Best Practices for Academic Libraries, published by Libraries Unlimited (978-1-4408-6203-8) is available for pre-order now, to be released in the Fall.

[1] Pierre N. Leval, Toward a Fair Use Standard, 103 Harv. L. Rev. 1105 (1990)

[2] Some others are the Society for Cinema and Media Studies’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use in Teaching for Film and Media Educators and the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Media Literacy Education.

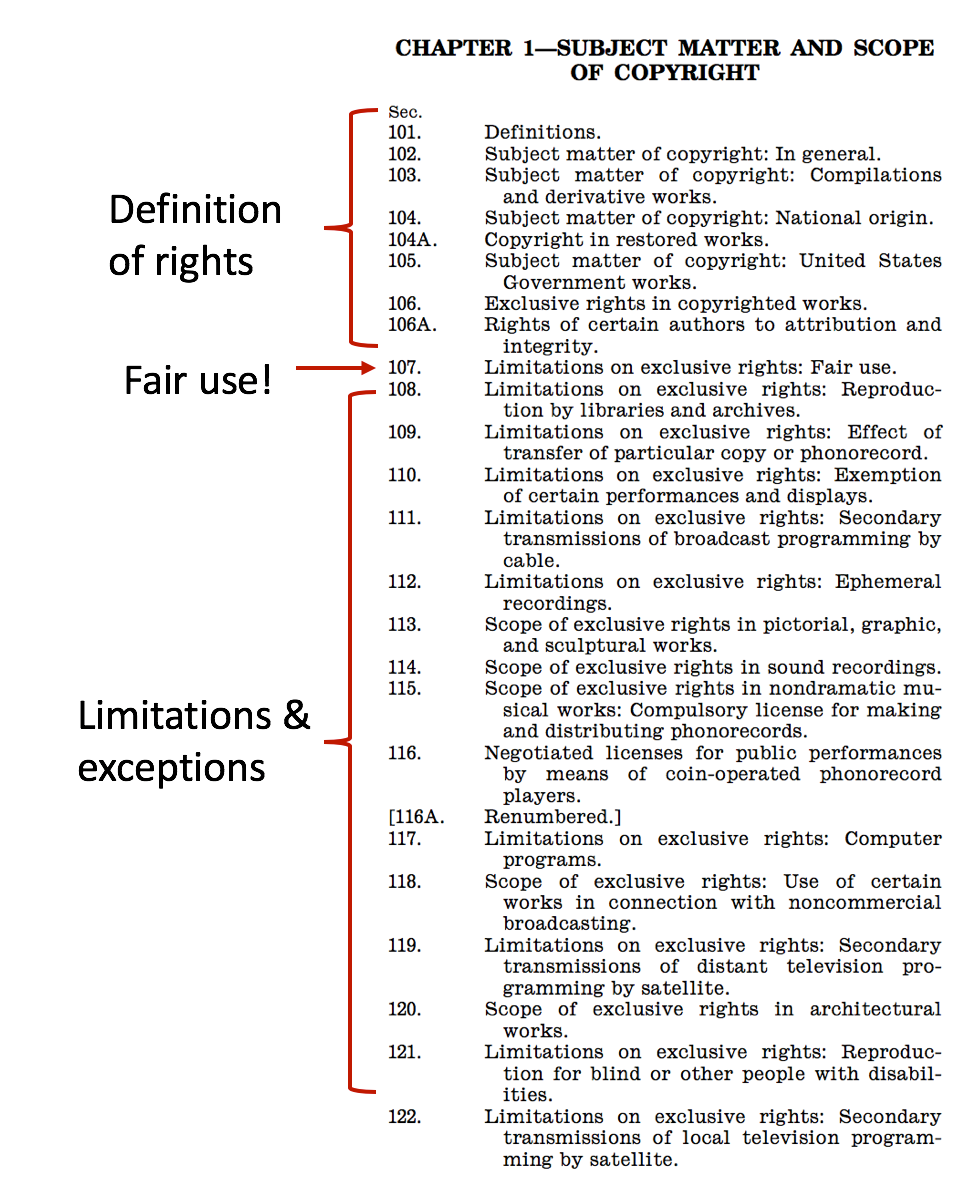

To understand how, it’s worth appreciating the structure of the Copyright Act. If you look at the table of contents of Chapter 1 of the Act (“Subject Matter and Scope of Copyright”), you see the first several sections define basic terms such as copyrightable subject matter. Included in that first half of the chapter is Section 106, which defines the exclusive rights held by rights holders: the right to control copying, the creation of derivative works, public distribution, public performance, and display. In the bottom half of the Act, Sections 108 to 122 provide for a wide variety of limitations and exceptions to those owners’ exclusive rights. These exceptions are largely for the benefit of users and the public, including specific exceptions to help libraries, teachers, blind and print-disabled users, non-commercial broadcast TV stations, and so on.

To understand how, it’s worth appreciating the structure of the Copyright Act. If you look at the table of contents of Chapter 1 of the Act (“Subject Matter and Scope of Copyright”), you see the first several sections define basic terms such as copyrightable subject matter. Included in that first half of the chapter is Section 106, which defines the exclusive rights held by rights holders: the right to control copying, the creation of derivative works, public distribution, public performance, and display. In the bottom half of the Act, Sections 108 to 122 provide for a wide variety of limitations and exceptions to those owners’ exclusive rights. These exceptions are largely for the benefit of users and the public, including specific exceptions to help libraries, teachers, blind and print-disabled users, non-commercial broadcast TV stations, and so on.  Further, this quote interprets another critical technology and fair use case from the U.S. Supreme Court,

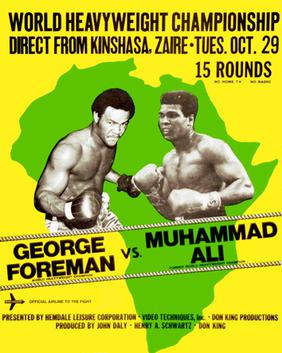

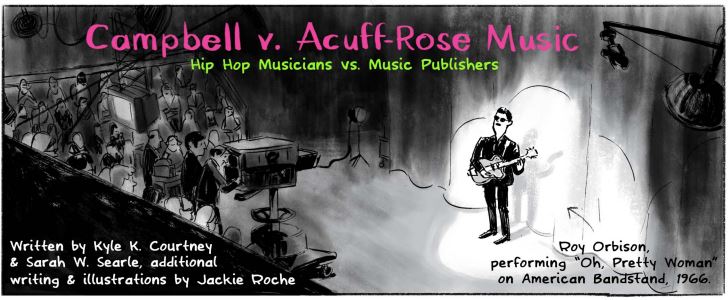

Further, this quote interprets another critical technology and fair use case from the U.S. Supreme Court,  Documentary filmmakers have relied heavily on the doctrine of fair use, which makes a lot of sense. If documentary filmmakers constantly had to rely on permission and licenses—which would also mean that a rightholder could refuse to grant permission—the result could be that these documentaries lacked proper historical references and context. In a 1996 case, the Southern District of New York refused to grant Turner Broadcasting’s motion for injunctive relief, finding that the clips of a boxing match film involving Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in a documentary about Muhammad Ali was likely a fair use. In Monster Communications, Inc. v. Turner Broadcasting Systems, the court noted that only a small portion of the total film—just 41 seconds—was taken and that the documentary used it for informational purposes.

Documentary filmmakers have relied heavily on the doctrine of fair use, which makes a lot of sense. If documentary filmmakers constantly had to rely on permission and licenses—which would also mean that a rightholder could refuse to grant permission—the result could be that these documentaries lacked proper historical references and context. In a 1996 case, the Southern District of New York refused to grant Turner Broadcasting’s motion for injunctive relief, finding that the clips of a boxing match film involving Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in a documentary about Muhammad Ali was likely a fair use. In Monster Communications, Inc. v. Turner Broadcasting Systems, the court noted that only a small portion of the total film—just 41 seconds—was taken and that the documentary used it for informational purposes.

Only then did Morse have any legal recourse, as international copyright did not exist. Alerted to Winterbotham’s book by Morse’s London publisher, John Stockdale, Morse immediately recruited Hamilton as his attorney, writing that “After going over the Work with care & a great deal of labour, I have estimated that nearly a third part of the whole of Winterbothams work, has been copied verbatim from my work, or about 600 pages out of about 2000.”

Only then did Morse have any legal recourse, as international copyright did not exist. Alerted to Winterbotham’s book by Morse’s London publisher, John Stockdale, Morse immediately recruited Hamilton as his attorney, writing that “After going over the Work with care & a great deal of labour, I have estimated that nearly a third part of the whole of Winterbothams work, has been copied verbatim from my work, or about 600 pages out of about 2000.” I thought I knew a fair bit about fair use—then I started

I thought I knew a fair bit about fair use—then I started

These misconceptions (and many others) arise from the

These misconceptions (and many others) arise from the  I’m excited to announce that I have a forthcoming book on this very topic, available later this year:

I’m excited to announce that I have a forthcoming book on this very topic, available later this year:

But it’s clear from our interviews with software preservation professionals that from their perspective, lots of software is in the same relationship to digital files as the player piano is to piano rolls. They call this “software dependency”—files created in a certain software environment depend on that software to be perceived. CAD files, word processing documents, spreadsheets, all look like gibberish, or do not reveal their full contents, unless

But it’s clear from our interviews with software preservation professionals that from their perspective, lots of software is in the same relationship to digital files as the player piano is to piano rolls. They call this “software dependency”—files created in a certain software environment depend on that software to be perceived. CAD files, word processing documents, spreadsheets, all look like gibberish, or do not reveal their full contents, unless