We are delighted to kick off the 8th Annual Fair Use Week with a guest post by the worldwide copyright expert, Kenneth D. Crews, as he contemplates an important question on the most recent U.S. copyright legislation. -Kyle K. Courtney

Can Fair Use Survive the CASE Act?

by Kenneth D. Crews

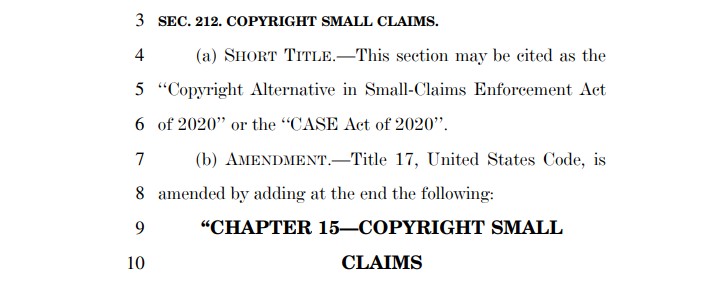

When Congress thinks of COVID, it seems to also think about copyright. Congress made that connection at a critical moment this last December. Embedded in the appropriations bill that gave emergency funding to citizens in need, was a thoroughly unrelated provision establishing a copyright “small-claims court,” where many future infringements may face their decider. The defense of fair use will also be on the docket.

The new law, known as the CASE Act, establishes the Copyright Claims Board within the U.S. Copyright Office, where parties may voluntarily allow their infringement cases to be heard. A copyright owner, as “claimant,” may choose to commence legal action in the new agency. The user of the work, or the “respondent,” may allow the matter to proceed or may choose to opt-out, effectively sending the case back to the copyright owner to decide whether to drop the matter or file a full-fledged lawsuit in federal court.

Realistically, this new court-like Board may be a dark hole where cases mysteriously disappear. Some claims will be filed and then bounced as the respondents opt-out. Other claims will be launched, and respondents will simply vanish or fail to understand or react at all, sending the matter into default. When a proceeding finally comes to fruition, the parties will investigate and present evidence, and the three appointed Copyright Claims Officers will determine the outcome of each case. Any claim of infringement will be subject to relevant defenses, such as expiration of the copyright, as well as fair use and other copyright exceptions.

The Copyright Claims Board will not open for business until late in 2021 at the soonest, but this is a good time to contemplate how fair use might play out. Think of these stages and possibilities:

Raising the Defense. A proceeding begins with the filing of a claim and the formal delivery of notice on the respondent. The first mention of fair use (or any other copyright exception) will typically appear in the respondent’s reply. But surely the claimant will foresee fair use asserted in many of these small-claims proceedings.

Gathering the Evidence. Courts and commentaries regularly remind us that fair use is a fact-specific matter, and the details of each case can determine the outcome. Staff attorneys working for the Board have the authority to investigate a matter, and the Officers have the authority to allow the introduction of evidence. Think of that fourth factor of fair use: the effect of the use on the market for or value of the work. A court will often need confidential economic data about the sales of the work in question and the revenue earned. The Copyright Claims Officers, parties, and staff attorneys do not have clear authority to compel disclosures and discovery. They can “request” documents and information. As a result, the Board could frequently be called upon to decide questions of fair use, but without the needed evidence. The choices at that point will be far from satisfactory.

Reporting the Decision. The Board is required to make a public disclosure of its decisions and the legal basis for rulings, but the statute includes few other details. The public announcement of a ruling might be little more than a conclusion, leaving only by implication the resolution of the fair use argument and the reasoning. On the other hand, the ruling on fair use could be an elaborate legal analysis. Because the parties have limited ability to appeal a ruling, the Officers might not feel the need to hand down complex opinions.

Depth of the Analysis. On the other hand, all judges know that their rulings on fair use are convincing to parties and lawyers only if their analyses are solidly persuasive. The same will be expected of the new Copyright Claims Officers, and for that reason they might want to pursue trenchant examinations of fair use. The Officers will also be looking to the parties for their arguments, and the parties are permitted to be represented by attorneys (or even by law students). Keep in mind that the typical proceeding will involve a modest use of a single work, and such users will also typically not be in position to retain specialized and expensive legal counsel. Consequently, the legal analyses presented to the Officers will often be far from equitable as between the parties.

Creation of Precedent. Decisions from the Copyright Claims Board will not be binding on anyone other than the immediate parties, and they officially will have no precedential value in later actions in a court or before the Board. Yet conventions of lawyering and the inevitability of human reasoning will surely press to the contrary. As the Board builds a record of rulings, the outcomes and the reasoning will undoubtedly be fodder for scrutiny and statistical tabulation. Individual rulings will in some manner be referenced in later proceedings. Analyses of trends and patterns will be pursued for their scholarly value and as insights for parties and attorneys thinking about the next case to come before the new Board.

Can fair use survive in this small-claims Board? Technically, the answer is definitely yes. However, fair use may also be vulnerable to distorted determinations, resulting from the lack of critical evidence, the pressure to manage a growing roster of legal proceedings, and the inequities of legal representation. Until the court can demonstrate a record of wise and effective rulings on fair use, any party to a claim that is likely to hinge on an innovative or nuanced question of fair use would probably we wise to opt-out of small claims and send the case to settlement or federal court.

Kenneth D. Crews is an attorney and copyright consultant in Los Angeles, and he was previously a faculty member and copyright policy officer at Indiana and Columbia Universities. He is the author numerous publications on fair use, including Copyright Law for Librarians and Educators, published by ALA Editions. The publisher has kindly made the new fourth edition of the book available at half price during Fair Use Week.

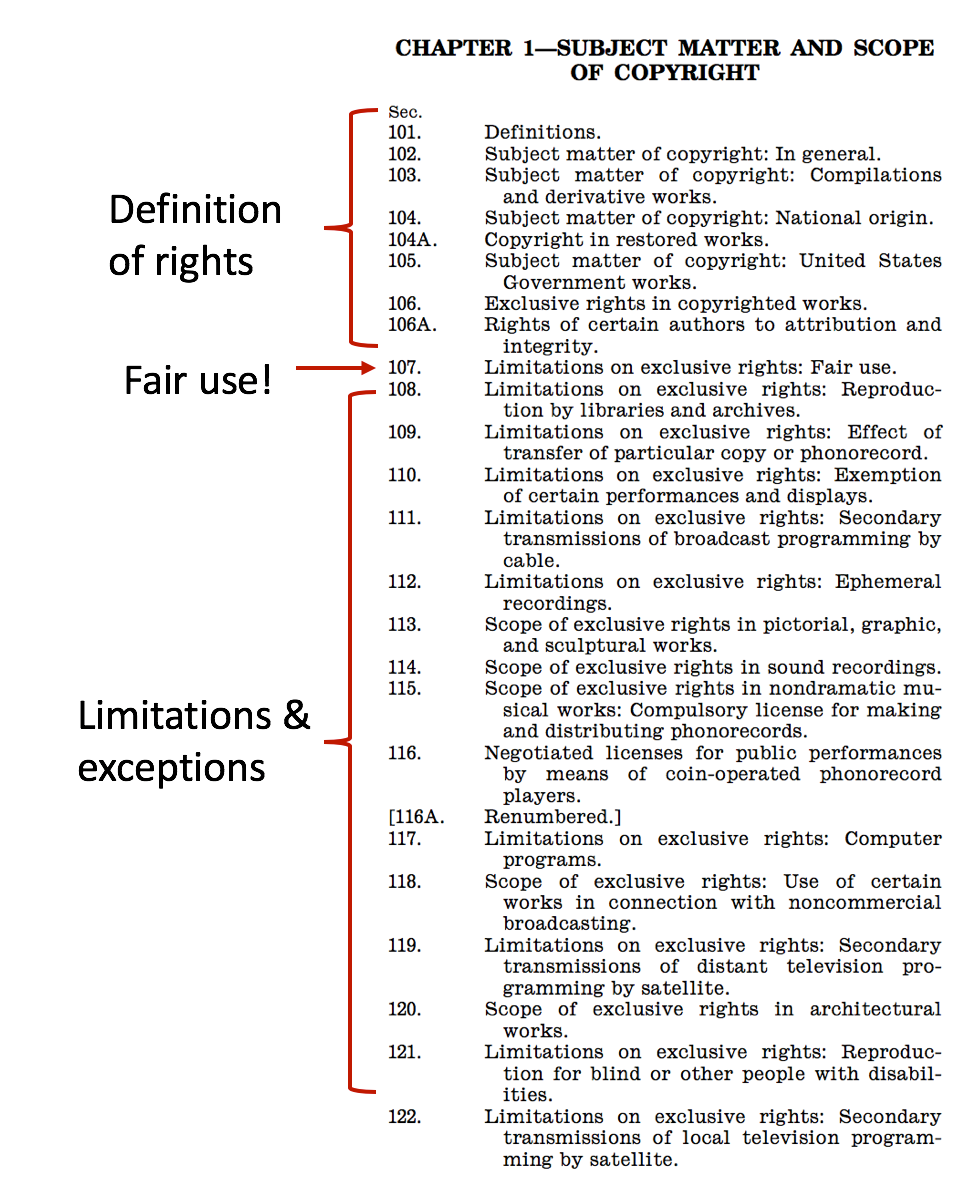

To understand how, it’s worth appreciating the structure of the Copyright Act. If you look at the table of contents of Chapter 1 of the Act (“Subject Matter and Scope of Copyright”), you see the first several sections define basic terms such as copyrightable subject matter. Included in that first half of the chapter is Section 106, which defines the exclusive rights held by rights holders: the right to control copying, the creation of derivative works, public distribution, public performance, and display. In the bottom half of the Act, Sections 108 to 122 provide for a wide variety of limitations and exceptions to those owners’ exclusive rights. These exceptions are largely for the benefit of users and the public, including specific exceptions to help libraries, teachers, blind and print-disabled users, non-commercial broadcast TV stations, and so on.

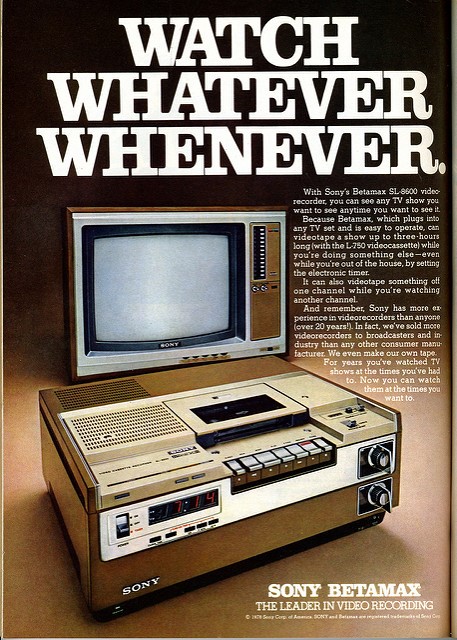

To understand how, it’s worth appreciating the structure of the Copyright Act. If you look at the table of contents of Chapter 1 of the Act (“Subject Matter and Scope of Copyright”), you see the first several sections define basic terms such as copyrightable subject matter. Included in that first half of the chapter is Section 106, which defines the exclusive rights held by rights holders: the right to control copying, the creation of derivative works, public distribution, public performance, and display. In the bottom half of the Act, Sections 108 to 122 provide for a wide variety of limitations and exceptions to those owners’ exclusive rights. These exceptions are largely for the benefit of users and the public, including specific exceptions to help libraries, teachers, blind and print-disabled users, non-commercial broadcast TV stations, and so on.  Further, this quote interprets another critical technology and fair use case from the U.S. Supreme Court,

Further, this quote interprets another critical technology and fair use case from the U.S. Supreme Court,  Only then did Morse have any legal recourse, as international copyright did not exist. Alerted to Winterbotham’s book by Morse’s London publisher, John Stockdale, Morse immediately recruited Hamilton as his attorney, writing that “After going over the Work with care & a great deal of labour, I have estimated that nearly a third part of the whole of Winterbothams work, has been copied verbatim from my work, or about 600 pages out of about 2000.”

Only then did Morse have any legal recourse, as international copyright did not exist. Alerted to Winterbotham’s book by Morse’s London publisher, John Stockdale, Morse immediately recruited Hamilton as his attorney, writing that “After going over the Work with care & a great deal of labour, I have estimated that nearly a third part of the whole of Winterbothams work, has been copied verbatim from my work, or about 600 pages out of about 2000.”