The second post of Day Four of the 10th Anniversary of Fair Use Week with a write up from Juliya Ziskina, Policy Fellow at Library Futures. Juliya examines two pending fair use cases and asks an important existential question. -Kyle K. Courtney

Is Fair Use Really the Answer to Life, the Universe, and Everything?

By Juliya Ziskina

Here on Harvard Library’s Fair Use Week blog, it is not a shocking statement to say that we love fair use. Fair use is both crucial and nebulous—indeed, its nebulousness is part of its design, given that it serves as a type of safe haven, decided on a case-by-case basis. Where statutes in the modern day are formulaic and often distilled into a multi-part judicial test, fair use is relatively open-ended, allowing judges a good amount of latitude—not just in terms of how to apply the doctrine, but also when. As such, fair use’s role in copyright law has grown as litigants and judges often use fair use as a backstop for other means of deciding copyright claims.

Fair use is undoubtedly important, but overreliance on it is not necessarily beneficial for the outcome of copyright cases, or even for the doctrine itself. As Authors Alliance Executive Director Dave Hansen wrote during Fair Use Week in 2020, there is a “pressure to look to fair use as a way to avoid other hard questions about other areas of copyright law. If we look to fair use to solve all our copyright questions, that pressure could start to water down and ultimately threaten the coherence of the doctrine.” Similarly, Public Knowledge Legal Director John Bergmayer wrote nearly 10 years ago: “If you love fair use, give it a day off once in a while.”

Exclusively relying on fair use can result in unintended consequences. Employing a fair use analysis when one is not necessarily needed can undermine the stability of the doctrine, and can preclude other means of analysis that are not only better suited to the facts of a case, but could create better precedent.

Two recent cases currently before the courts are meaningful examples of Bergmayer’s and Hansen’s prescient observations: Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, and American Society for Testing and Materials, et al. v. Public.Resource.Org. I’ll examine each of these in turn, and discuss why fair use was applied too broadly in Warhol and is also not the suitable framework for ASTM v. Public.Resource.Org.

Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith

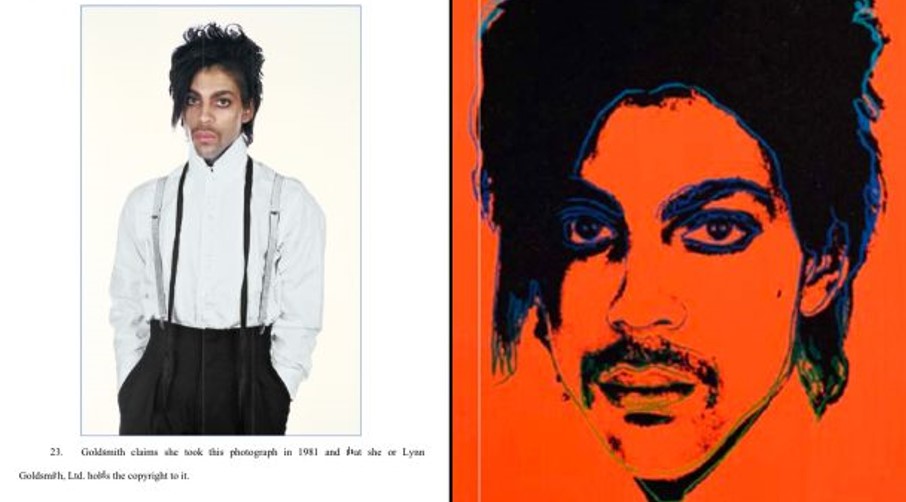

In 1984, photographer Lynn Goldsmith licensed to Vanity Fair the right to use one of her photographs of Prince for the purpose of creating an illustration that Vanity Fair was commissioning for an article. Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol created the illustration for Vanity Fair. Further—also unbeknownst to Goldsmith—Warhol used Goldsmith’s photograph to create 15 additional works using the silkscreen process, known as his Prince Series.

Goldsmith claims that she first discovered the existence of the Prince Series after Prince’s death in 2016, when Vanity Fair used one of the Prince Series images in a tribute issue. The Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) sought a declaratory judgment that the Prince Series was fair use. Goldsmith counterclaimed for copyright infringement.

The lower court ruled in favor of AWF, finding that Warhol’s work was transformative and therefore that it was a fair use. The Second Circuit reversed on appeal. The Second Circuit focused on visual similarity of the works and the fact that both were “created as works of visual art” and are “portraits of the same person.” The Second Circuit refused to “seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works” contrary to the Supreme Court in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, which instructed that courts must view a work as transformative if it adds a new “meaning or message.” (Importantly, the Campbell Court also made clear that a finding of transformative use, while important, is not necessary for a finding of fair use.)

And, as such, the district court and the Second Circuit positioned Warhol and its fair use analysis as revolving around a single, critical concept: “transformativeness.” The issue with this is that the vast majority of modern courts already use the transformative use concept throughout the fair use inquiry as the dominant means of resolving various fair use questions. Once courts determine that a use is transformative, that determination often seems to dictate the rest of the fair use analysis and, ultimately, the case’s outcome. As one study asked: “is transformative use eating the fair use world?”

Warhol is a useful example. Rather than centering on the lawfulness of the Prince Series, the lower courts should have focused more narrowly on the lawfulness of the Andy Warhol Foundation’s licensing of the Prince Series for reproduction and distribution in Vanity Fair. Judge Dennis Jacobs argued in his concurring opinion that, properly understood, this case does not necessarily address whether the creation of appropriation art is a fair use, but whether the licensing of a derivative image for widespread distribution in a magazine is a fair use. According to Judge Jacobs, fair use is about uses, not works. Perhaps, he offered, some uses of the Prince Series may be within the scope of fair use, even if others are not. Specifically, while licensing the Prince Series as images of Prince competes directly with Goldsmith’s exploitation of her photograph, the creation of the original artworks did not, nor do other sorts of licenses (such as museum displays).

Why does it matter that the courts viewed the Warhol case through a broad fair use lens? As detailed in the Library Futures, et. al. amicus brief, this decision could impact libraries and archives because research, teaching, scholarship, and preservation rely on the stability of fair use.

Why does it matter that the courts viewed the Warhol case through a broad fair use lens? As detailed in the Library Futures, et. al. amicus brief, this decision could impact libraries and archives because research, teaching, scholarship, and preservation rely on the stability of fair use.

Upending our understanding of fair use could upend many of a library’s functions and make it harder for libraries and researchers to leverage fair use to create new research tools or improve accessibility of collections, such as in Authors Guild v. Google and Authors Guild v. HathiTrust. Incidentally, in an attempt to make fair use more predictable to supposedly ensure consistent application, the Court risks undermining the stable understanding of fair use that has already existed since Campbell. This potential result could have been avoided by taking a narrower fair use view.

American Society for Testing and Materials, et al. v. Public Resource Org

ASTM v. Public.Resource Org, currently pending in the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, is also a case that unsuitably applies a fair use analysis. In ASTM v. Public.Resource Org, several major industry associations, including ASTM, are suing to prevent Public.Resource.Org, a small, but mighty nonprofit organization, from posting reference standards (such as building codes) online. Many agency regulations incorporate reference standards developed by private organizations, such as ASTM. Although these standards have the force and effect of law once they are incorporated in agency regulations, they are not printed in the Federal Register or the Code of Federal Regulations and they can often be difficult for the public to access. ASTM sells hard copies and digital versions, and makes their standards available for free online in “read-only” mode. Public.Resource.org—an organization devoted to making laws and other government documents available to the public—purchased physical copies of the plaintiffs’ standards and scanned and digitized copies to make them freely available online to the public. All of these standards have been incorporated by reference into federal law. ASTM and other standard development organizations sued Public.Resource Org for copyright infringement.

The district court concluded that such standards as incorporated into the law are protectable by copyright. On appeal, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and remanded, sidestepped addressing whether the standards retain copyright after incorporation by reference into law, and instead instructed the lower court to analyze the Public.Resource Org’s use of the standards (e.g. posting them online) primarily through the lens of fair use. The court recognized that there is a spectrum of incorporated standards that ranges from those that “impose legally binding requirements” to those that “serve as mere references but have no direct legal effect.” This wide variation created difficulties in determining which standards are actually “the law.” This conclusion led to the court’s sole focus on Public.Resource Org’s fair use defense. In March 2022, the lower court issued an opinion that would allow Public.Resource Org to reproduce 184 standards under fair use, partially reproduce one standard, and deny reproduction of 32 standards that were found to differ in substantive ways from those incorporated by law. ASTM appealed the case to the D.C. Circuit, where it is currently pending.

Performing this analysis through a fair use lens precludes a more important discussion about copyrightability and public access to the law. As argued in the Library Futures, et. al. amicus brief in support of Public.Resource.org, when a law-making entity incorporates a standard by reference into a rule or regulation, the contents of the whole of that publication must be freely and fully accessible by the public. No one can own the law, and because fair use is only relevant for copyrighted works and not those in the public domain, it should not be the primary analysis here.

Performing this analysis through a fair use lens precludes a more important discussion about copyrightability and public access to the law. As argued in the Library Futures, et. al. amicus brief in support of Public.Resource.org, when a law-making entity incorporates a standard by reference into a rule or regulation, the contents of the whole of that publication must be freely and fully accessible by the public. No one can own the law, and because fair use is only relevant for copyrighted works and not those in the public domain, it should not be the primary analysis here.

By framing the case through a fair use analysis, the court also avoids grappling with a broader question: what constitutes reasonable access to the law? Arguably, ASTM’s “online reading rooms” are not a sufficient substitute for unrestricted access to the law, because they are not actually “free.” In order to obtain access, ASTM requires users to register with their personal information, and agree to a voluminous, multi-part privacy policy and a nearly 1000-word contract that restricts users from transmitting the documents or performing simple cut and paste tasks. This scenario brings to mind an exchange about access in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy:

“But the plans were on display…”

“On display? I eventually had to go down to the cellar to find them.”

“That’s the display department.”

“With a flashlight.”

“Ah, well, the lights had probably gone.”

“So had the stairs.”

“But look, you found the notice, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” said Arthur, “yes I did. It was on display on the bottom of a locked filing cabinet stuck in a disused lavatory with a sign on the door saying ‘Beware of the Leopard.’”

–Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Judge Katsas, in his concurrence in ASTM v. Public.Resource.Org, echoed a similar idea, noting that “access to the law cannot be conditioned on the consent of a private party, just as it cannot be conditioned on the ability to read fine print posted on high walls.”

Ironically, the fair use analyses in AWF v. Goldsmith and ASTM v. Public.Resource.Org should be swapped: rather than centering on the works themselves, the Warhol Court should be centering on the use of the works at issue; and, rather than centering on Public.Resource.Org’s use of the standards, the court should be centering on the copyrightability of the standards themselves.

These cases illustrate the important point that, despite how much we love fair use, before we jump to its analysis we should ask: “Is it copyrightable in the first place?” and “Is there a better lens through which to look at this case?”

Juliya Ziskina is a Policy Fellow at Library Futures and an attorney in New York City. While she was a law student, Juliya co-founded and led a successful initiative for an institutional open access policy at the University of Washington.

But it’s clear from our interviews with software preservation professionals that from their perspective, lots of software is in the same relationship to digital files as the player piano is to piano rolls. They call this “software dependency”—files created in a certain software environment depend on that software to be perceived. CAD files, word processing documents, spreadsheets, all look like gibberish, or do not reveal their full contents, unless

But it’s clear from our interviews with software preservation professionals that from their perspective, lots of software is in the same relationship to digital files as the player piano is to piano rolls. They call this “software dependency”—files created in a certain software environment depend on that software to be perceived. CAD files, word processing documents, spreadsheets, all look like gibberish, or do not reveal their full contents, unless