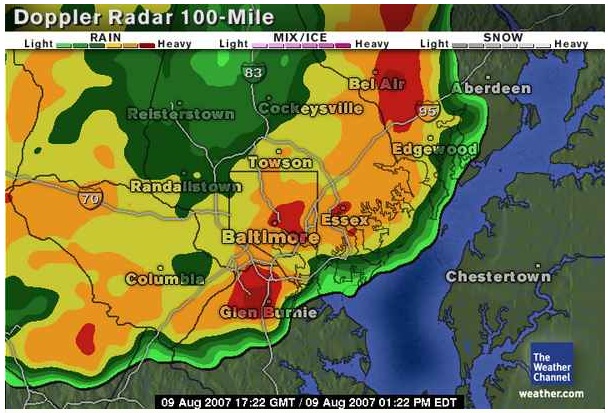

I’m in one of the yellow areas in the dopper radar map above. My wife and kid are in a rental car in a dark red area, driving into BWI for a flight home that I suspect may be delayed. Meanwhile power is out at my daughter’s family’s house. I’m sitting in a chair on the front porch, enjoying the thunderstorm, connected to the Net by EvDO on the cell system. It’s an old neighborhood, so the yard and road are shaded by large old oak, maple and elm trees. The rain drips twice in front of the porch, once from the sky onto the house and trees, and once from the leaves onto the ground. I don’t see much lightning, but the thunder is a low, almost constant rumble, tumbling across the sky, as if vast boulders were rolling around on an invisble metal ceiling. Tire treads from cars rolling by make long kissing sounds on wet pavement. These too have doppler effects, rising in tone on approach and dropping as they depart. There is an urgency to driving I don’t share here on the porch. We are in two different Newtonian states: bodies in motion and bodies at rest. Observation by drivers is mandatory, but only through narrow cones of relevance, one constantly oncoming, the other receding in rear-view mirrors. Observation by trees and porch-sitters is optional. Which makes this post an indulgence.

I have Linux Journal work to do. That’s fun too, watching from afar what’s happening at Linux World Expo in San Francisco. The Net too is a natural environment: a true public marketplace of the ancient type — a noisy place where people gather to do business and make culture. Yet even as we enlarge this place more every day, it seems we understand it less. The Net, for all its finite and fully revealed complexities, is no less mysterious the rest of Creation. Life is nothing if not extravagant and original and mysterious at its original core — on the Net no less than ground soaked by rain.

Recently at Harvard we had a meeting where the subject of the Internet as a “public good” was discussed. For all the excellent thought and conversation we shared, it seemed to me we failed, unavoidably to grip a fundamental question from which all answers must be gounded. Namely, What is the Net?

We have knowledge of this no less than we have knowledge of life. We know it, we experience it, yet we cannot explain the origins of its origins, which are neither chicken nor egg. Whitman writes,

The press of my foot to the earth

springs a hundred affections.

They scorn the best I can do to relate them.These are the thoughts of all men in all ages and lands.

They are not original with me.

If they are not yours as much as mine

they are nothing or next to nothing.

If they do not enclose everything they are next to nothing.

If they are not the riddle and the undying of the riddle

they are nothing.

If they are not just as close as they are distant

they are nothing.This is the grass that grows

wherever the land is and the water is.

This is the common air that bathes the globe.

Is the Net no less a globe than the one on which we walk? I wonder.

We made the Net. We are its gods. Yet our voices are not those of burning bushes. They are the buzz of the public marketplace. Is this place — where you and I are now — any less holy, or even primeval, than a forest floor? I suggest it isn’t, because at its core is a fecund nothingness: a zero-distance void between you and I and each of us who choose to connect on it. The working distance between you and I right now is less than between myself and the family inside this house — a fact that slightly bothers me. Yet, when I shut the lid on this laptop, the distance between you and I will return to the finite: no less close than that between readers and the authors of books. Now the proximal is returned to advantage: I will step inside a door to visit a baby just a few days old: a full self where a year ago there was none. When he becomes conscious of his own original mysteries, what will he see?

Here’s what Whitman saw:

Rise after rise bow the phantoms behind me.

Afar down I see the huge first Nothing,

the vapor from the nostrils of death.

I know I was even there.

I waited unseen and always.

And slept while God carried me

through the lethargic mist.

And took my time.Long I was hugged close. Long and long.

Infinite have been the preparations for me.

Faithful and friendly the arms that have helped me.Cycles ferried my cradle, rowing and rowing

like cheerful boatmen;

For room to me stars kept aside in their own rings.

They sent influences to look after what was to hold me.Before I was born out of my mother

generations guided me.

My embryo has never been torpid.

Nothing could overlay it.

For it the nebula cohered to an orb.

The long slow strata piled to rest it on.

Vast vegetables gave it substance.

Monstrous animals transported it in their mouths

and deposited it with care.All forces have been steadily employed

to complete and delight me.

Now I stand on this spot with my soul.I know that I have the best of time and space.

And that I was never measured, and never will be measured.I tramp a perpetual journey.

My signs are a rainproof coat, good shoes

and a staff cut from the wood.Each man and woman of you I lead upon a knoll.

My left hand hooks you about the waist,

My right hand points to landscapes and continents,

and a plain public road.Not I, nor any one else can travel that road for you.

You must travel it for yourself.It is not far. It is within reach.

Perhaps you have been on it since you were born

and did not know.

Perhaps it is everywhere on water and on land.Shoulder your duds, and I will mine,

and let us hasten forth.

Humans are traveling animals. More than upright walkers, we are runners. I have read that a healthy young adult, or a small pack of them, can run almost indefinitely, and surely exhausted many a meal. The human diaspora spread out of Africa like a stain across everywhere on water and land, all in in the span of a few dozen millennia. Now our shouldered duds are laptops and cell phones, and no longer just staffs cut from wood. Is this bad? I suggest it is no less natural. We are less “digital natives” than beings that extend their senses and powers by making tools and then making things from those tools that further extend their senses and powers. By powers of indwelling our vehicles become extensions of our greater selves. It is not for lack of fact that drivers speak of “my fender” and fliers speak of “my wings”. We are skilled at being far more than our fleshy sleves. And we lean toward movement, always hastening down the public road.

Whitman concludes,

The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me.

He complains of my gab and my loitering.I too am not a bit tamed. I too am untranslatable.

I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.The last scud of day holds back for me.

It flings my likeness after the rest and true as any

on the shadowed wilds,

It coaxes me to the vapor and the desk.I depart as air.

I shake my white locks at the runaway sun.

I effuse my flesh in eddies and drift in lacy jags.I bequeath myself to the dirt and grow

from the grass I love.

If you want me again look for me under your boot soles.You will hardly know who I am or what I mean.

But I shall be good health to you nevertheless.

And filtre and fiber your blood.Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged.

Missing me one place search another

I stop some where waiting for you.

Here, for example. Wherever this is.

Leave a Reply