…all experience is an arch wherethrough

Gleams that untravelled world, whose margin fades

For ever and for ever when I move.

How dull it is to pause, to make an end…

— Alfred, Lord Tennyson: Ulysses

Here’s how dull that pause — that end we call the front page — has become:

And yet every newspaper needs one. So it’s not going away. But to stay current — literally — papers need something else as well — something Net-native that bridges the static page and the live flow of actual news.

And yet every newspaper needs one. So it’s not going away. But to stay current — literally — papers need something else as well — something Net-native that bridges the static page and the live flow of actual news.

Twitter isn’t it.

Yes, these days it’s pro forma for news media to post notifications of stories and other editorial on Twitter, but Twitter is a closed and silo’d corporation, not an institutional convention on the order of the front page, the editorial page, the section, the insert. Most of all, Twitter is somebody else’s system. It’s not any paper’s own.

But Twitter does normalize a model that Dave Winer called a river, long before Twitter existed. You might think of a river as a paper’s own Twitter. And also the reader’s.

In the early days Twitter was called a “microblogging” platform. What made it micro was its 140-character limit on posts. What made it blogging was its format: latest stuff on top and a “permalink” to every post. (Alas, Twitter posts tend to be snow on the water, flowing to near-oblivion and lacking syndication through RSS —though there are hacks.)

Dave created RSS — Really Simple Syndication — as we know it today, and got The New York Times and other publications (including many papers and nearly all Web publishers) to adopt it as well. Today a search for “RSS” on Google brings up over two billion results.

Now Dave has convened a hackathon for creating a new river-based home page for newspapers, starting once again with The New York Times. On his blog he explains how a river of news aggregator works. And in a post at Nieman Journalism Lab he explains Why every news organization should have a river. There he unpacks a series of observations and recommendations:

- News organizations are shrinking, but readers’ demand for news is exploding.

- The tools of news are available to more people all the time.

- News organizations have to redefine themselves.

- Users have a special kind of insight that most news orgs don’t tap.

- Therefore, the challenge for news organizations has been, for the last couple of decades, to learn how to incorporate the experience of these users and their new publishing tools, into their product — the news.

- Like anything else related to technology, this will happen slowly and iteratively.

- The first thing you can do is show the readers what you’re reading.

- Having the river will also focus your mind.

- Then, once your river is up and running for a while, have a meeting with all your bloggers.

— and then offers real help for getting set up.

I want to expand the reach of this work to broadcasting: a business that has always been live, has always had flow, and has been just as challenged as print in adapting to the live-networked world.

I want to focus first on the BBC, not just because they’re an institution with the same great heft as the Times, but because they’ve invited me to visit with them and talk about this kind of stuff. I’ll be doing that in a couple of weeks. By coincidence Neil Midgley in Forbes yesterday reported that the BBC News Division would be cutting five hundred jobs over the next two years. I’m hoping this might open minds at the Beeb toward opportunity around news rivers.

In the traditional model, reporting works something like hunting and gathering. A reporter hunts on his or her beat, gathers details for stories, and then serves up meals that whet and fill the appetites of readers, viewers and listeners. This model won’t go away. In some ways it’s being improved. Here in the U.S. ProPublica and the Center for Public Integrity are good examples of that. But it will become part of a larger flow, drawing from a wider conceptual and operational net.

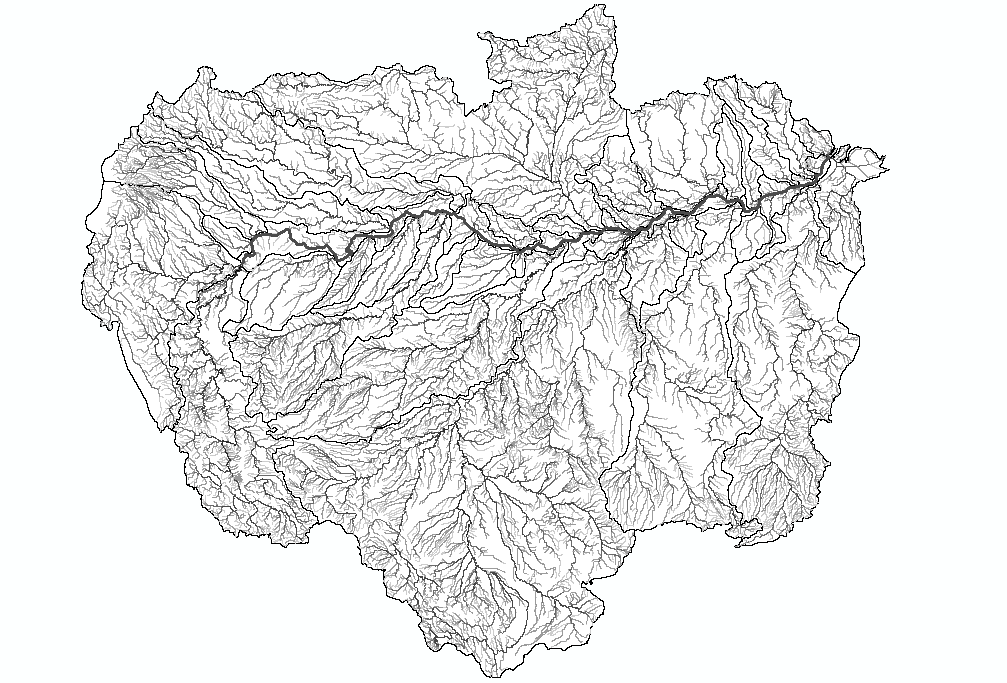

A river for media as major as the Times and the BBC flows in the center of a vast watershed, with sources flowing inward through tributaries. Each of those sources can be lakes, streams and rivers as well. At their best, all of them sustain life, culture and commerce along their banks and in the areas surrounding them.

For institutions such as the Times and the BBC, what matters is maintaining their attraction to sources, destinations, and lives sustained in the process. That attraction is flow itself. That’s why rivers are essential as both metaphor and method.

To help with this, let’s look at a watershed in the physical world that works on roughly the scale that the Times and the BBC do in the journalistic regions they serve:

That’s the Amazon River basin. Every stream and river in that basin flows down a slope toward the Amazon River. While much of the rain that falls on the basin sinks into the earth and sustains life right there, an excess flows downstream. Some of the water and the material it carries is used and re-used along the way. Much of the activity within each body operates in its own local or regional ecosystem. But much of it flows to the main river before spilling into the sea. The entire system is shaped by its boundaries, the ridges and plateaus farthest upstream. Its influence extends outside those boundaries, of course, but what makes the whole watershed unitary is inward flow toward the central river.

That’s the Amazon River basin. Every stream and river in that basin flows down a slope toward the Amazon River. While much of the rain that falls on the basin sinks into the earth and sustains life right there, an excess flows downstream. Some of the water and the material it carries is used and re-used along the way. Much of the activity within each body operates in its own local or regional ecosystem. But much of it flows to the main river before spilling into the sea. The entire system is shaped by its boundaries, the ridges and plateaus farthest upstream. Its influence extends outside those boundaries, of course, but what makes the whole watershed unitary is inward flow toward the central river.

In his Nieman piece, Dave identifies bloggers as essential sources. (Remember that blogs have a river format of their own: they flow, from the tops to the bottoms of their own pages.) Email is another source. So are comments on a news organization’s own stories. So are other publications. So are news agencies such as the Associated Press. So are think tanks, industry experts and investigative organizations such as the Center for Public Integrity.

Missing from that list are ordinary people. All of those people are in position to be sources for stories, and many already contribute to news flow through the likes of Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Every one of those intermediary systems cries out for improvement or replacement, both of which will be happen naturally if they feel the by the gravitational pull of rivers at central journalistic institutions such as the Times and the BBC.

But the most important challenge is leveraging what Dan Gillmor famously said many years ago, when he was still at the San Jose Mercury News: “My readers know more than I do.”

As a visiting scholar in Journalism at NYU for the last two years, I have participated in many classes led by Jay Rosen and Clay Shirky. (Most of those were in the Studio 20 program, which Jay describes as “a consultancy paid in problems.”) One subject that often came up in these classes was the institutionalized power asymmetry between news media on one hand and people they serve on the other — even as the preponderance of power to provide news material clearly resides on the side of the people, rather than the media. You can see this asymmetry in the way comments tend to work. Think about the weakness one feels when writing a letter to the editor, or to comment under a story on a news site — and how lame both often tend to be.

This last semester I worked for awhile with a small group of students in one of Clay’s classes, consulting The Guardian — one of the world’s most innovative news organizations. What the students contemplated for awhile was finding ways for readers with subject expertise or useful knowledge to bypass the comment process and get straight to reporters. I would like to see future classes look toward rivers as one way (or context within which) this can be done.

The Guardian is far more clueful than the average paper, but it would still benefit hugely from looking at itself as a river rather than … well, I’m not sure what. It used to be that http://guardian.co.uk went to the paper itself, but now it detects my location and redirects me to http://www.theguardian.com/us. And when I click on the “About us” link, it goes to this front-page-ish thing. In other words, packed with lots of stuff, as front pages of newspaper websites tend to be these days. Which is fine. They have to do something, and this is what they’re doing now. Live and learn, always. But one thing they’re learning that I don’t like — as a reader and possible contributor — is made clear by several items that appear on the page. One is the little progress thingie at the bottom, which shows stuff behind the page that is still trying to load (no kidding) long after I went to the page ten minutes ago:![]()

![]()

![]() Another is this item at the bottom of the page:

Another is this item at the bottom of the page:![]() And another is this piece — one among (let’s see…) 24 items with a headline and text under it:

And another is this piece — one among (let’s see…) 24 items with a headline and text under it:

The operative word here is content.

The operative word here is content.

John Perry Barlow once said, “I didn’t start hearing about ‘content’ until the container business felt threatened.” But fear isn’t the problem here. It’s the implication that stories, posts and other editorial matter are all just cargo. Stuff.

The mind-shift going on here is that’s a huge value-subtract for both paper and reader alike. (Yes, I know there is no substitute for content, other than the abandoned “editorial,” and that’s a problem too.)

Speaking as a reader of the Guardian — and one who reads it in the UK, the US and many other countries on the World Wide Freaking Web — I hate being blindered by national borders, and regarded as just an “audience” member valued mostly as an “influential” instrument to be “engaged” by “branded content,” even it’s laundered through a “Lab.”

This kind of jive is the sound an industry makes when it’s talking to itself. Or worse, of editorial and publishing factota dancing on the rubble of the Chinese wall that long stood between them, supporting independence and integrity on both sides.

If the Guardian saw itself as a river, and not as a cargo delivery system, it might not have made the moves in the U.S. that it has so far. To fully grok how big a problem these moves have been (again, so far), read The Guardian at the Gate, by Michael Wolff in GQ.

Newspapers and broadcast networks tend to be regional things: geographically, culturally, and politically. The Guardian’s position — what Reis and Trout (in Positioning: the Battle for Your Mind) call a creneau — has been its preëminence as the leading newspaper for culture and leftish politics in the UK. Creating something new and separate in the U.S. was, and remains, weird. It would be even more weird if the BBC tried the same thing. (Instead, wisely, it’s just another program source for U.S. public radio. And its voice is clearly a UK one.)

Another term from the marketing world that’s making its way over to the production side of media (including news) is “personalization.” At the literal level this isn’t a bad thing. One might like to personalize, or have personalized, some of the stuff one reads, hears or watches. But the way marketers think about it, personalization is something done by algorithms that direct content toward individuals, guided by the crunchings of surveillance-gathered Big Data.

Some of that stuff isn’t bad. Some might actually be good. But the better thing would be to start with the role of the paper, or the broadcast system, as a river that flows through the heart of an ecosystem that it also defines. That role is not just to barge content downstream, but to collect and grow shared knowledge.

We’re at the beginning of the process of discovering all the things a river can be. This is why Dave’s hackathon is so important.

RSS gave newspapers a new lease on life at a time when the old one was running out. Rivers will do the same if newspapers, broadcasters and other essential media leverage them with the same gusto.

It helps that, at the heart of both RSS and rivers, there are old and well-understood concepts. For RSS it’s syndication. For rivers it’s publishing. Both RSS and rivers use these old concepts in new ways that work for everybody, and not just for the media themselves.

Curation is another one. It comes up nearly every time I talk to a news organization about what only it can do, or what it can do better than any other institution. Some curation should be done by the media themselves. But it should be done in the context of the new world defined by the Net and the Web. That’s why I suggest flowing rivers into the free and open Web. Don’t lock them behind paywalls. My one-liner for this is Sell the news and give away the olds. It’s off-topic for rivers, syndication and the Live Web, but it’s a topic worth pursuing, because old news can always have new value, if it’s free.

And that’s what the Net and the Web were born to be — for everybody and everything: free. Just like the sea into which all rivers flow.

Back to Tennyson:

Come, my friends,

‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

Leave a Reply