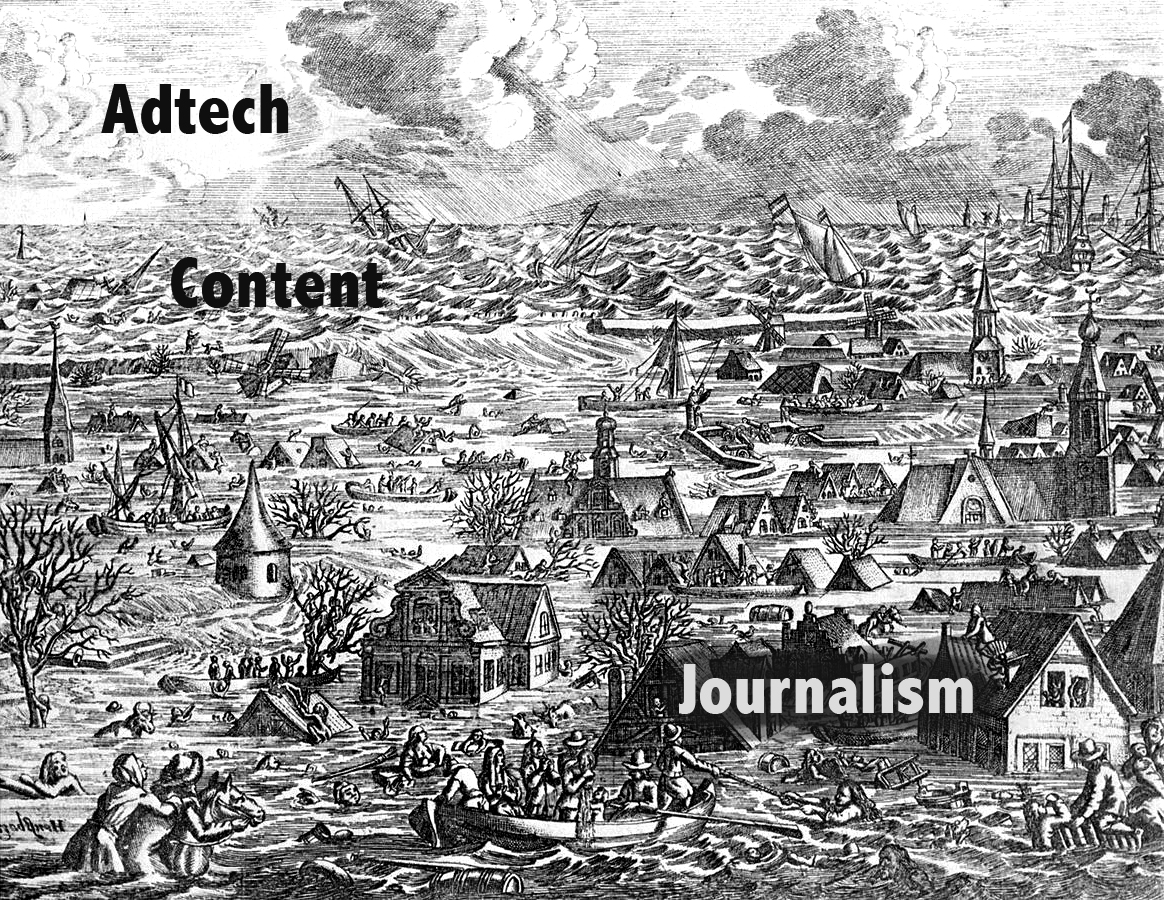

Journalism is in a world of hurt because it has been marginalized by a new business model that requires maximizing “content” instead. That model is called adtech.

We can see adtech’s effects in The New York Times’ In New Jersey, Only a Few Media Watchdogs Are Left, by David Chen. His prime example is the Newark Star-Ledger, “which almost halved its newsroom eight years ago,” and “has mutated into a digital media company requiring most reporters to reach an ever-increasing quota of page views as part of their compensation.”

That quota is to attract adtech placements.

While adtech is called advertising and looks like advertising, it’s actually a breed of direct marketing, which is a cousin of spam and descended from what we still call junk mail.

Like junk mail, adtech is driven by data, intrusively personal, looking for success in tiny-percentage responses, and oblivious to harms it causes, which include wanton and unwelcome surveillance, annoying the shit out of people and filling the world with crap.

But adtech is far worse, because it also funds hyper-partisan news flows, including vast rivers of fake news, much of it from pop-up publishers that are as fake as the clickbait they maximize. Without adtech, fake news would be marginalized to the digital equivalent of supermarket tabloids.

Here’s one way to tell the difference between real advertising and adtech:

- Real advertising wants to be in a publication because it values the publication’s journalism and readership.

- Adtech wants to push ads at readers anywhere it can find them.

Here’s one way to tell the difference between journalism and content:

- Journalism has ethics.

- Content has volume.

Another:

- Journalism is supported by advertising and subscriptions.

- Content is supported by adtech.

Companies advertising in the old publishing world were flattered to appear in publications like the Star-Ledger. They were also considered sponsors of those publications.

Companies advertising in the new publishing world are drunk on digital and want to maximize the “big data” they acquire. And there are thousands of bartenders to help with that.

As I wrote in Separating Advertising’s Wheat and Chaff, in the new publishing world “Madison Avenue fell asleep, direct response marketing ate its brain, and it woke up as an alien replica of itself.”

That’s also why, to operate in publishing’s new alien-built economy, journalists need to meet that “ever-increasing quota of page views.” Better to “generate content” than to do the best journalism we can, the proposition goes. It’s still a losing one.

See, adtech doesn’t care about journalism, because its economy incentives maximizing the sum of content in the world, so it has as many places as possible to chase followed eyeballs with ads. Case in point, from @WaltMossberg:

About a week after our launch, I was seated at a dinner next to a major advertising executive. He complimented me on our new site’s quality and on that of a predecessor site we had created and run, AllThingsD.com. I asked him if that meant he’d be placing ads on our fledgling site. He said yes, he’d do that for a little while. And then, after the cookies he placed on Recode helped him to track our desirable audience around the web, his agency would begin removing the ads and placing them on cheaper sites our readers also happened to visit. In other words, our quality journalism was, to him, nothing more than a lead generator for target-rich readers, and would ultimately benefit sites that might care less about quality.

If Recode insisted on real ads, rather than coming to depend on surveillance-based adtech, its advertisers would have valued the publication, and not just the eyeballs of its readers, wherever it could find them.

Walt concludes,

It’s no easy task to either make money online as a publisher or to advertise your product in a world where attention is so fleeting and divided. But the current system of ad-supported web content isn’t working for readers and viewers. It needs to be reset.

The ad business is too brain-snatched to do that reset alone. It needs help from readers and brave publishers willing to stop participating in the adtech game.

As I explain in How customers can debug business with one line of code (hashtag: #NoStalking), each of us can come to publishers with a simple term that says “Just show me ads not based on tracking me.” In other words, “Give us real advertising. We can live with that.”

#NoStalking is not only in the works at Customer Commons, but saying yes to it will be an ideal move by companies wishing to obey the General Data Protection Regulation (aka GDPR), which will start punishing stalking severely, starting in 2018.

While the GDPR will blow up adtech as we’ve known it, #NoStalking will save real advertising, and the best of ad-supported publishing along with it, because it will bring economic incentives back into alignment with journalism. We had that in the old ad-and-subscription supported world of offline journalism, and we can get it back in the new world of online journalism. As I explain in Why #NoStalking is a good deal for publishers,

Individuals issuing the offer get guilt-free use of the goods they come to the publisher for, and the publisher gets to stay in business — and improve that business by running advertising that is actually valued by its recipients.

So, if you want to save journalism, the best of publishing and civil discourse that depends on both, bring back real advertising and cure the cancer of adtech.

For more help with that, go back and read Don Marti’s Targeting failure: legit sites lose, intermediaries win. You might also visit the Adblock War Series at my blog.

Two bonus links:

- Don Marti‘s What The Verge can do to help save web advertising

- Ethan Zuckerman’s It’s Journalism’s Job to Save Civics.

…

The original version of this post was published in Medium on 23 January 2017. This is an experiment in publishing first in Medium and second here. We’ll see how it goes.

Save

Leave a Reply