In the library of Earth’s history, there are missing books, and within books there are missing chapters, written in rock that is now gone. John Wesley Powell recorded the greatest example of gone rock in 1869, on his expedition by boat through the Grand Canyon. Floating down the Colorado River, he saw the canyon’s mile-thick layers of reddish sedimentary rock resting on a basement of gray non-sedimentary rock, the layers of which were cocked at an angle from the flatnesses of every layer above. Observing this, he correctly assumed that the upper layers did not continue from the bottom one, because time had clearly passed between when the basement rock was beveled flat, against its own grain, and when the floors of rock above it were successively laid down. He didn’t know how much time had passed between basement and flooring, and could hardly guess.

The answer turned out to be more than a billion years. The walls of the Grand Canyon say nothing about what happened during that time. Geology calls that nothing an unconformity.

In the decades since Powell made his notes, the same gap has been found all over the world and is now called the Great Unconformity. Because of that unconformity, geology knows close to nothing about what happened in the world through stretches of time up to 1.6 billion years long.

All of those absent records end abruptly with the Cambrian Explosion, which began about 541 million years ago. That’s when the Cambrian period arrived and with it an amplitude of history, written in stone.

Many theories attempt to explain what erased such a large span of Earth’s history, but the prevailing guess is perhaps best expressed in “Neoproterozoic glacial origin of the Great Unconformity”, published on the last day of 2018 by nine geologists writing for the National Academy of Sciences. Put simply, they blame snow. Lots of it: enough to turn the planet into one giant snowball, informally called Snowball Earth. A more accurate name for this time would be Glacierball Earth, because glaciers, all formed from accumulated snow, apparently covered most or all of Earth’s land during the Great Unconformity—and most or all of the seas as well. Every continent was a Greenland or an Antarctica.

The relevant fact about glaciers is that they don’t sit still. They push immensities of accumulated ice down on landscapes and then spread sideways, pulverizing and scraping against adjacent landscapes, bulldozing their ways seaward through mountains and across hills and plains. In this manner, glaciers scraped a vastness of geological history off the Earth’s continents and sideways into ocean basins, where plate tectonics could hide the evidence. (A fact little known outside of geology is that nearly all the world’s ocean floors are young: born in spreading centers and killed by subduction under continents or piled up as debris on continental edges here and there. Example: the Bay Area of California is an ocean floor that wasn’t subducted into a trench.) As a result, the stories of Earth’s missing history are partly told by younger rock that remembers only that a layer of moving ice had erased pretty much everything other than a signature on its work.

I bring all this up because I see something analogous to Glacierball Earth happening right now, right here, across our new worldwide digital sphere. A snowstorm of bits is falling on the virtual surface of our virtual sphere, which itself is made of bits even more provisional and temporary than the glaciers that once covered the physical Earth. Nearly all of this digital storm, vivid and present at every moment, is doomed to vanish because it lacks even a glacier’s talent for accumulation.

The World Wide Web is also the World Wide Whiteboard.

Think about it: there is nothing about a bit that lends itself to persistence, other than the media it is written on. Form follows function; and most digital functions, even those we call “storage”, are temporary. The largest commercial facilities for storing digital goods are what we fittingly call “clouds”. By design, these are built to remember no more of what they once contained than does an empty closet. Stop paying for cloud storage, and away goes your stuff, leaving no fossil imprints. Old hard drives, CDs, and DVDs might persist in landfills, but people in the far future may look at a CD or a DVD the way a geologist today looks at Cambrian zircons: as hints of digital activities that may have happened during an interval about which nothing can ever be known. If those fossils speak of what’s happening now at all, it will be of a self-erasing Digital Earth that was born in the late 20th century.

This theory actually comes from my wife, who has long claimed that future historians will look at our digital age as an invisible one because it sucks so royally at archiving itself.

Credit where due: the Internet Archive is doing its best to make sure that some stuff will survive. But what will keep that archive alive, when all the media we have for recalling bits—from spinning platters to solid-state memory—are volatile by nature?

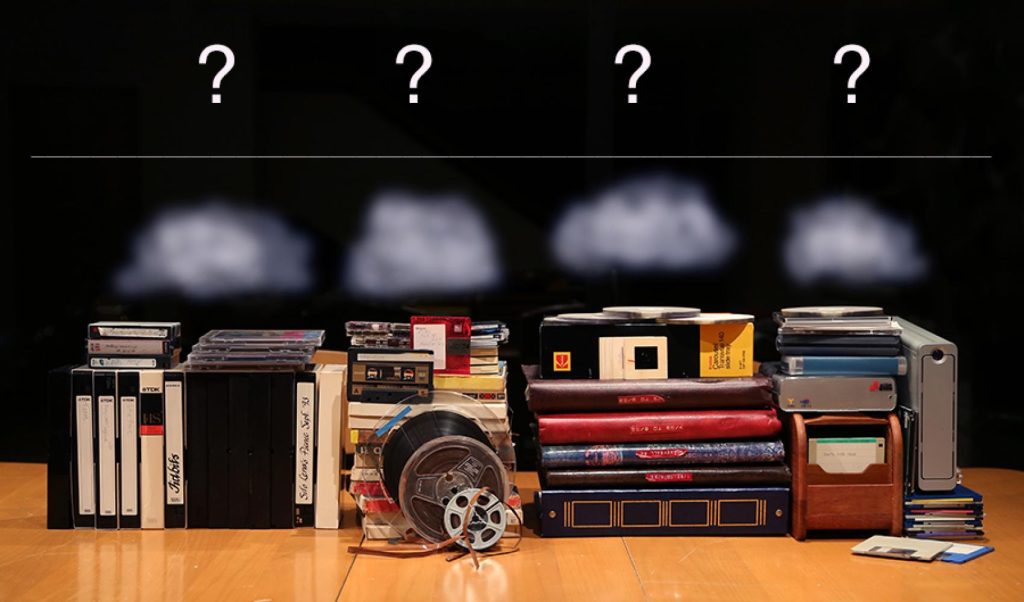

My own future unconformity is announced by the stack of books on my desk, propping up the laptop on which I am writing. Two of those books are self-published compilations of essays I wrote about technology in the mid-1980s, mostly for publications that are long gone. The originals are on floppy disks that can only be read by PCs and apps of that time, some of which are buried in lower strata of boxes in my garage. I just found a floppy with some of those essays. (It’s the one with a blue edge in the wood case near the right end of the photo above.) If those still retain readable files, I am sure there are ways to recover at least the raw ASCII text. But I’m still betting the paper copies of the books under this laptop will live a lot longer than will these floppies or my mothballed PCs, all of which are likely bricked by decades of un-use.

As for other media, the prospect isn’t any better.

At the base of my video collection is a stratum of VHS videotapes, atop of which are strata of MiniDV and Hi8 tapes, and then one of digital stuff burned onto CDs and stored in hard drives, most of which have been disconnected for years. Some of those drives have interfaces and connections (e.g. FireWire) no longer supported by any computers being made today. Although I’ve saved machines to play all of them, none I’ve checked still work. One choked to death on a CD I stuck in it. That was a failure that stopped me from making Christmas presents of family memories recorded on old tapes and DVDs. I meant to renew the project sometime before the following Christmas, but that didn’t happen. Next Christmas? The one after that? I still hope, but the odds are against it.

Then there are my parents’ 8mm and 16mm movies filmed between the 1930s and the 1960s. In 1989, my sister and I had all of those copied over to VHS tape. We then recorded our mother annotating the tapes onto companion cassette tapes while we all watched the show. I still have the original film in a box somewhere, but I haven’t found any of the tapes. Mom died in 2003 at age 90, and her whole generation is now gone.

The base stratum of my audio past is a few dozen open reel tapes recorded in the 1950s and 1960s. Above those are cassette and micro-cassette tapes, plus many Sony MiniDisks recorded in ATRAC, a proprietary compression algorithm now used by nobody, including Sony. Although I do have ways to play some (but not all) of those, I’m cautious about converting any of them to digital formats (Ogg, MPEG, or whatever), because all digital storage media are likely to become obsolete, dead, or both—as will formats, algorithms, and codecs. Already I have dozens of dead external hard drives in boxes and drawers. And, since no commercial cloud service is committed to digital preservation in the absence of payment, my files saved in clouds are sure to be flushed after neither my heirs nor I continue paying for their preservation. I assume my old open reel and cassette tapes are okay, but I can’t tell right now because both my Sony TCWE-475 cassette deck (high end in its day) and my Akai 202D-SS open-reel deck (a quadrophonic model from the early ’70s) are in need of work, since some of their rubber parts have rotted.

The same goes for my photographs. My printed photos—countless thousands of them dating from the late 1800s to 2004—are stored in boxes and albums of photos, negatives and Kodak slide carousels. My digital photos are spread across a mess of duplicated backup drives totaling many terabytes, plus a handful of CDs. About 60,000 photos are exposed to the world on Flickr’s cloud, where I maintain two Pro accounts (here and here) for $50/year apiece. More are in the Berkman Klein Center’s pro account (here) and Linux Journal‘s (here). I doubt any of those will survive after those entities stop getting paid their yearly fees. SmugMug, which now owns Flickr, has said some encouraging things about photos such as mine, all of which are Creative Commons-licensed to encourage re-use. But, as Geoffrey West tells us, companies are mortal. All of them die.

As for my digital works as a whole (or anybody’s), there is great promise in what the Internet Archive and Wikimedia Commons do, but there is no guarantee that either will last for decades more, much less for centuries or millennia. And neither are able to archive everything that matters (much as they might like to).

It should also be sobering to recognize that nobody truly “owns” a domain on the internet. All those “sites” with “domains” at “locations” and “addresses” are rented. We pay a sum to a registrar for the right to use a domain name for a finite period of time. There are no permanent domain names or IP addresses. In the digital world, finitude rules.

So the historic progression I see, and try to illustrate in the photo at the top of this post, is from hard physical records through digital ones we hold for ourselves, and then up into clouds… that go away. Everything digital is snow falling and disappearing on the waters of time.

Will there ever be a way to save for the very long term what we ironically call our digital “assets?” Or is all of it doomed by its own nature to disappear, leaving little more evidence of its passage than a Great Digital Unconformity, when everything was forgotten?

I can’t think of any technical questions more serious than those two.

The original version of this post appeared in the March 2019 issue of Linux Journal.

Leave a Reply