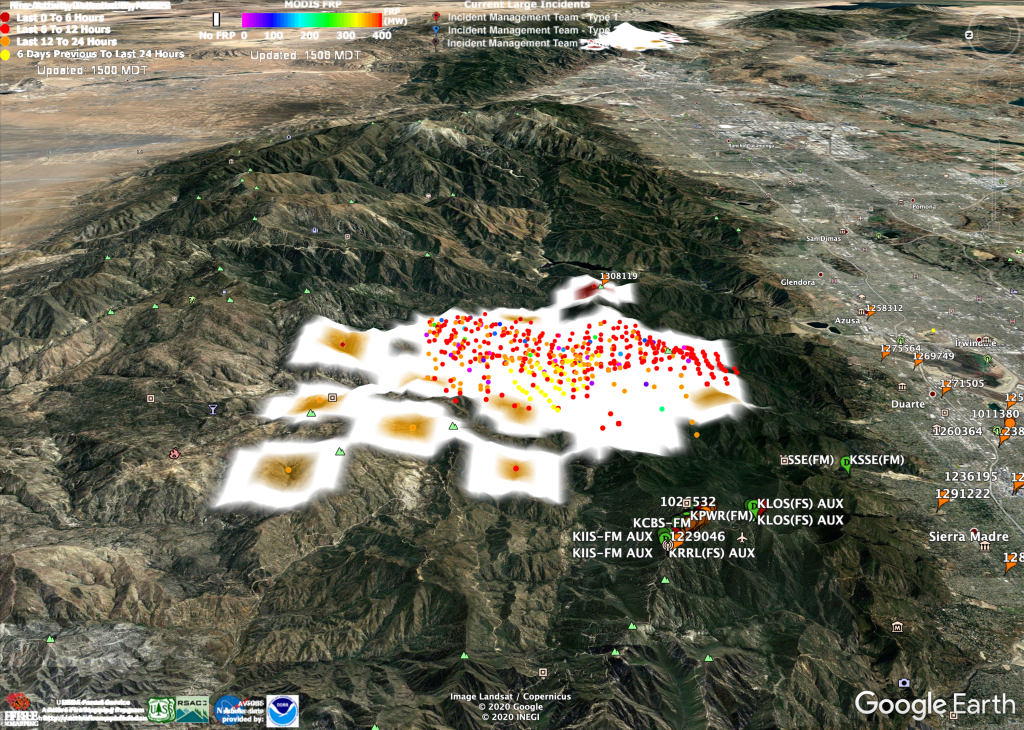

The white mess in the image above is the Bobcat Fire, spreading now in the San Gabriel Mountains, against which Los Angeles’ suburban sprawl (that’s it, on the right) reaches its limits of advance to the north. It makes no sense to build very far up or into these mountains, for two good reasons. One is fire, which happens often and awfully. The other is that the mountains are geologically new, and falling down almost as fast as they are rising up. At the mouths of valleys emptying into the sprawl are vast empty reservoirs—catch basins—ready to be filled with rocks, soil and mud “downwasting,” as geologists say, from a range as big as the Smokies, twice as high, ready to burn and shed.

Outside of its northern rain forests and snow-capped mountains, California has just two seasons: fire and rain. Right now we’re in the midst of fire season. Rain is called Winter, and it has been dry since the last one. If the Bobcat fire burns down to the edge of Monrovia, or Altadena, or any of the towns at the base of the mountains, heavy winter rains will cause downwasting in a form John McPhee describes in Los Angeles Against the Mountains:

The water was now spreading over the street. It descended in heavy sheets. As the young Genofiles and their mother glimpsed it in the all but total darkness, the scene was suddenly illuminated by a blue electrical flash. In the blue light they saw a massive blackness, moving. It was not a landslide, not a mudslide, not a rock avalanche; nor by any means was it the front of a conventional flood. In Jackie’s words, “It was just one big black thing coming at us, rolling, rolling with a lot of water in front of it, pushing the water, this big black thing. It was just one big black hill coming toward us.

In geology, it would be known as a debris flow. Debris flows amass in stream valleys and more or less resemble fresh concrete. They consist of water mixed with a good deal of solid material, most of which is above sand size. Some of it is Chevrolet size. Boulders bigger than cars ride long distances in debris flows. Boulders grouped like fish eggs pour downhill in debris flows. The dark material coming toward the Genofiles was not only full of boulders; it was so full of automobiles it was like bread dough mixed with raisins. On its way down Pine Cone Road, it plucked up cars from driveways and the street. When it crashed into the Genofiles’ house, the shattering of safety glass made terrific explosive sounds. A door burst open. Mud and boulders poured into the hall. We’re going to go, Jackie thought. Oh, my God, what a hell of a way for the four of us to die together.

Three rains ago we had debris flows in Montecito, the next zip code over from our home in Santa Barbara. I wrote about it in Making sense of what happened to Montecito. The flows, which destroyed much of the town and killed about two dozen people, were caused by heavy rains following the Thomas Fire, which at 281,893 acres was biggest fire in California history at the time. The Camp Fire, a few months later, burned a bit less land but killed 85 people and destroyed more than 18,000 buildings, including whole towns. This year we already have two fires bigger than the Thomas, and at least three more growing fast enough to take the lead. You can see the whole updated list on the Los Angeles Times California Wildfires Map.

For a good high-altitude picture of what’s going on, I recommend NASA’s FIRMS (Fire Information for Resource Management System). It’s a highly interactive map that lets you mix input from satellite photographs and fire detection by orbiting MODIS and VIIRS systems. MODIS is onboard the Terra and Aqua satellites; and VIIRS is onboard the Suomi National Polar-Orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP) spacecraft. (It’s actually more complicated than that. If you’re interested, dig into those links.) Here’s how the FIRMS map shows the active West Coast fires and the smoke they’re producing:

That’s a lot of cremated forest and wildlife right there.

I just put those two images and a bunch of others up on Flickr, here. Most are of MODIS fire detections superimposed on 3-D Google Earth maps. The main thing I want to get across with these is how large and anomalous these fires are.

True: fire is essential to many of the West’s wild ecosystems. It’s no accident that the California state tree, the Coast Redwood, grows so tall and lives so long: it’s adapted to fire. (One can also make a case that the state flower, the California Poppy, which thrives amidst fresh rocks and soil, is adapted to earthquakes.) But what’s going on here is something much bigger. Explain it any way you like, including strange luck.

Whatever you conclude, it’s a hell of a show. And vice versa.

Leave a Reply