Internet Search Engines and Trademark Rights

By Luckie HONG

Published at China Law & Practice, March 2009

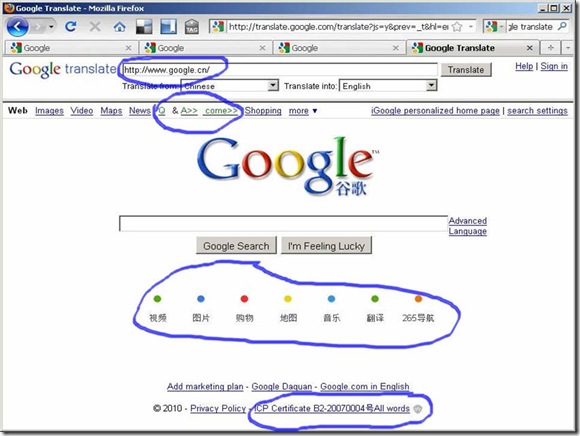

Google and Baidu have become household names in China. Both companies provide internet search services, and both now offer keyword advertising programmes. Under these programmes, companies can purchase certain keywords – when a user searches for these words, targeted advertising is displayed, often in the form of links to the companies’ own websites.

Recent cases from the Courts of PRC in Beijing, Guangzhou and Shanghai have again raised questions relating to keyword advertising programmes. The issue at stake is whether the purchase or sale of keywords that constitute the whole or part of another party’s registered trademark can be classified as trademark infringement under Chinese law.

RIGHTS OWNERS DEMANDING ACTION

Trademark holders are now challenging keyword advertising in China; such challenges have also been made in other jurisdictions worldwide for a considerable time. As far back as 1999, the United States Court of the Ninth Circuit issued an opinion in Brookfield Communications Inc. v. West Coast Entertainment Corp., 174 F.3d 1036 (9th Cir. 1999), in which the Court intimated, based on the plain meaning of the Lanham Act, that the purchase of search terms is a use in commerce and furthermore constitutes trademark infringement after the likelihood of confusion analysis.

The Paris Court of Appeal held in 2006 that Google’s practice of selling certain words as triggers for sponsored advertisement amounted to infringement of Louis Vuitton Malletier’s trademark. Google appealed, and the French Supreme Court has referred questions on keyword advertising to the European Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling.

There have been a significant number of cases in the US and EU in connection to keyword advertising. This has caused rights owners in China to worry about their interests in this new context. On the other hand, rights owners can not ignore the huge impact of the new kind of online advertising among young Chinese consumers: Nielsen, a market research company, estimates that online advertising revenue in China in the third quarter of 2008 grew 42% from a year earlier to Rmb3.72 billion (US$543 million). This rate was more than double the growth in spending on television, newspaper or magazine advertising.

Before making important decisions as to who to sue, and where, it is important for legal practitioners advising rights owners to examine the legal frame and recent cases.

PREVIEW OF LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF PRC

The two parties involved as rights owners’ opponents in issue are the companies purchasing keywords and the search engines providing advertising programmes, namely “subscribers” and “providers” of the keyword advertising. Under the current Trademark Law, different regulations apply on these two parties:

Article 52 of the Trademark Law prescribes that, one form of infringement on the exclusive rights over a registered trademark is “using a trademark that is identical with or similar to the registered mark on the same or similar goods without permission of the owner of the registered trademark. To define furtherly the meaning of “using”, Article 3 of the Trademark Implementing Regulations illustrates that the using of a trademark in advertisement or promotion is included in the scope of “using” referred in the Trademark Law. Should the keyword service be classified as a form of “advertisement”, the subscribers are subject to the review of the Trademark Law.

On the other hand, the legitimacy of providers’ sale of keywords is dependent on a different basis. Article 50 of the Regulations prescribes that, “to intentionally provide any other person with…, and other convenient conditions” shall be an act of infringement of the exclusive right of a registered trademark. Thus it can be said that, in the case the subscriber of the keyword advertising unduly use the term included in a registered trademark, the advertising service provider who did not fulfil its duty of care should also bear the infringement liability.

The space for discretion left to China’s courts is mainly on the two issues. The first is whether the new arising keyword advertising programme falls into the range of the “advertisement” set out in the Regulations, and the second is to what extent the search engines should take the duty of care in running their keywords business.

BUYING TRADEMARKED WORDS TRIGGERING UNFAIR COMPETITION

In one case, the plaintiff, Jijia Intellectual Property Agency, initially sued rival company Guang Lixin IP, along with Google, for unfair competition in violation of the PRC Anti-unfair Competition Law. The action pertained to the purchase and sale by Guang and Google of trademarked terms belonging to Jijia. The terms were used as keywords which triggered so-called sponsored links on Google’s search results pages. Jijia complained in addition of the intentional passing off caused by Guang: the website to which users were directed by the sponsored link was designed using a similar colour, style and organisation. It also contained identical pictures and introductory text to those used on Jijia’s own site.

After the court accepted the case, Jijia withdrew its complaint against Google. This left Guang alone to confront indictments over purchasing keywords as well as misusing pirated content on its website.

Among other things, the district court at the outset examined the fact pattern regarding “keyword advertising” or “sponsored links” involved in Jijia case, and eventually held in the plaintiff’s favour. The court’s views were, in summary, that:

a) the sponsored link used here by Google is a new kind of advertising service in which the client can fulfil its marketing strategy by purchasing keywords which enable its website address to appear at the top of the search results page;

b) a real competition relationship exists between the plaintiff and the defendant;

c) the sponsored link wrongly directing users proves the bad faith of the defendant through exploiting the plaintiff’s brand reputation for commercial purposes, and meanwhile drives traffic which ought to be the plaintiff’s potential clients to its rival through a fraudulent channel; and

d) this conduct violates the Good Faith Principle and widely accepted business morality, and should be found as an unfair competitive activity.

On the basis of the above grounds, the court ruled against the plaintiff and awarded damages of Rmb100,000 to Jijia.

SPLIT OF AUTHORITY ON SEARCH ENGINE LIABILITY

In a 2008 case from Guangzhou Baiyun District, the Court analysed a similar fact pattern to that in Jijia and intimated that the function of Google’s AdWords service was to help users conveniently discover links to those enterprises or merchants who have purchased keywords from search engines, saying to bring more users’ attention to the business information belonging to the service subscribers. In conclusion, the alleged infringing conduct in nature should be held a new kind of advertising activity through certain medium in the unauthorised way in which the plaintiff owned trademark was used in commerce.

Interestingly, Guangzhou Court found that Google, which was also the joint defendant in that case, did not have the ability of editing or monitoring the internet information entered by a subscriber to the company’s AdWords service, and hence Google should not bear the duty of care to the information in dispute. Accordingly, the Guangzhou Court found Google innocent of trademark infringement in the context of a keyword service.

Ironically, in an even earlier case, another large search company, Baidu, had confronted the completely opposing stand of Shanghai No.2 Intermediate Court. The Shanghai Court concluded that in the case where a third party used another’s trademarked words without authorisation, Baidu did not duly perform its duty of care and hence should be imposed with a civil liability. In addition to the injunction order, the Court awarded damages of Rmb50,000 against Baidu for its joint infringement.

To sum up the common ground on which the two courts are standing, it can be said that Shanghai and Guangzhou both hold that the purchase of keywords falling in the scope of another party’s exclusive right over the trademark perpetrates trademark infringement. Infringement is not only limited to the range of unfair competition stated by the Beijing Court. However, the law is divided here on the issue of whether the search engine’s sale of keywords, or the advising service, should be found to be infringing. Shanghai said yes, but Guangzhou’s answer was no.

LESSONS LEARNT

The examination of the three cases above reveals that the Chinese courts have not yet reached consensus on issues including the duty of care of a search engine which provides a keyword service, and the application of joint infringement theory to relevant cases. In the absence of guidance from a higher level, some lessons can be learnt on the basis of court practices observed until now in China.

The first clue is that, feeding off the hot debate in US and EU on what constitutes “use in commerce” for purposes of trademark infringement in the context of internet usage, China’s courts hold a common view that keywords are a new type of advertising under the regulation of the Trademark Law. At the same time, the Anti-unfair Competition Law also provides a legal basis for a rights claim.

The second suggestion is regarding rights owners and their choice of against whom they should claim their trademark rights: the service users or the service providers (the search engine companies). The stories in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou all show that if the subscriber to a keyword service can be confirmed, and their keyword usage is established to be unauthorised and causing actual confusion or likelihood of confusion among consumers, then the best choice is to pursue the service user.

The third implication is the possibility of forum shopping for the rights owners. In cases where the subscribers are not easy to locate, or where they are incapable of paying damages, the plaintiff can only pursue the search engines to obtain relief from trademark infringement. The winner in any such dispute seems to be wholly dependant on the forum. Judging by the limited disclosed cases in China, rights owners should prefer Shanghai to other jurisdictions.