Click here to view a PDF version.

As a born and raised Muslim, much of my experience has been shaped by my alienation as a minority in the United States. I oscillated throughout my youth between the worldly need to be seen by my non-Muslim, American peers and the celestial desire to be loved by Allah. At times I reconciled the two spheres by convincing myself that validation from my peers and professors was Allah’s way of seeing me. I put my worth in other creations of God, instead of centering God’s love within myself. This dilemma defines my upbringing in the United States and is a crucial starting point as I reflect on this course: I arrived to Aesthetic Thinking 54 with the vestiges of that material desires lurking within me. I have not unlearned them entirely, but I am well on my way as a consequence of the intimate art I was afforded the opportunity to bear witness to—throughout history and from my peers. Additionally, the historical movements to which we brought our varied perspectives and the localized explorations of religiosity further challenged me to understand and accept that a collective Islam will always be beyond me, and will continue to take on varied interpretations with every community or individual I encounter.

Arguably the largest takeaways from this course came from the initial readings and lectures, when we asked difficult questions around the construction of Islam as the “Other” in Western society. Professor Asani’s centering of the cultural studies approach not only functioned as an anchor for me, but challenged my preconceived notions about the actions and ritualistic practices that are considered Islamic. I was most challenged by the reading on the Berti erasure, as the notion of drinking the Qur’an was one so far removed from my devout Sunni Arab upbringing. Asking “Whose Islam? Which Islam? In which context?” forced me to reconcile the internalized Sunni Arab hegemony that I am normally so critical of. I felt the privilege I have within the global Muslim community once again when we watched Koran My Heart and saw so many Muslims from around the world: West Africa, South Asia, and other parts of the Middle East, flocking to Egypt for a chance at recognition. Again, I had to reconcile that knee jerk reaction I have to be critical of Sunni Arabs, when I myself am a descendent of a very hegemonic and pervasive tradition.

As a woman, our exploration of the postcolonial power flux allowed me to center the Islam I was raised with in a historical movement with particular patriarchal and sectarian motives. Encountering figures like Rifa’a al Tahtawi and Sir Muhammad Iqbal added a different dimension to what I had envisaged as the linear Islamist movements that took place throughout the Muslim world after Europeans left. Rifa’a al Tahtawi’s saying “In Paris I saw Islam and no Muslims, but in Egypt I see Muslims but no Islam” is one I have heard from older Egyptians. It is not until I took this course, though, that I began exploring what this phrase means; prior to this class I had a much starker Western/Eastern approach and assumed that figures like Tahtawi were people who betrayed their Egyptian cohort by taking on European notions of liberation. As a consequence of our discussion of Islam/islam in the Qur’an, I now understand that Tahtawi was simply referencing a particular ethos of education, knowledge, and interpersonal relations that he would have liked to see more of in Egypt. While I still hold that critiquing the likes of Tahtawi (or Qasim Amin, who we did not discuss) is valuable, I now understand that the delineations I created because of my own limited understanding of the transmission of knowledge during colonial encounters has hindered me from understanding the intersectionality of colonial and diasporic epistemology.

Conversely, Iqbal’s message in his Call and Answer left me critical of the way in which the colonial encounter was justified. The answer Allah gives to the troubled Muslims is similar to Tahtawi’s claim: “Infidels who live like Muslims surely merit Faith’s reward.” I struggled with this claim because I do not think that Allah rewarded the colonizers if He took their souls in the process. How can a people for whom their technology and innovation is predicated upon the mass destruction and consumption of other lands be spiritually free? The weeks we spent exploring the politicization of Islam and the incorporation of Western thinkers (such as Neitzsche in the case of Iqbal) left me with an all-consuming question. It is, in essence, the same question I ask myself on a daily basis: Is spiritual recognition from Allah evident through “progress” or “success” on this world or dunya? In the same way that I turned to my American peers for validation, I feel that many colonized Muslim countries initially wanted to “advance themselves” by turning toward European powers as templates of that progression.

This revelation was coupled by my newfound awareness when we discussed certain aspects of Islam I had always taken for granted: the five pillars, hijab, the hadith, and the order in which the Qur’anic verses were revealed. I did not know that the Qur’an makes no mention of the now normative five pillars. When Asani told us that many Muslims today use those pillars as a metric for piety, I felt a pang: I, too, do so even though Allah knows I do not live up to my faith in so many ways. Conversely, learning that the pillars are not enforced in the Qur’an gave me permission to not hold myself to that standard, either. I gained a greater understanding of the depth and breadth of Allah’s love when I learned that so much of what is held as a model within the normative community has also been subject to the ebb and flow of history and memory. Learning about “Ilm al Rijal,” isnad, and the three tiers of hadith (sahih, hasan, and daif) also cemented in me the realization that these religious texts are subject to human fallibilities and regardless of the veracity that undergirds them, they are humanly compiled. Similarly, I was taught that all non-Muslims were infidels, but our discussion of islam/Islam, “Ahl al Bayt,” and the order of the verses revealed showed me that greater complexity shaped the revelation of the Qur’an: the faith was revealed through stages of delineation and only in the centuries following the death of the prophet did it take on a political flavor to demarcate what is and is not “Islam.”

All of these examples are only to emphasize the question I must return to in order to proceed: Whose Islam? The only thing I am certain of after this course is that my faith is in my hands, and that I cannot entirely turn toward history in order to find my answers. My journey must continue inward. In an attempt to center my relationship with Allah, I took very seriously some of the creative works we explored: Conference of the Birds, the painting of Sheik Ahmadou Bamba of Senegal, Persepolis, and the Turkish Mevladi. Each of these spoke to a different aspect of my identity and qualms as a first generation Muslim woman of color living in the United States—a country marred by its history of injustice and hatred toward those who are deemed Other.

With my first post, I attempted to explore light as it literally exists around me. I thought this would be an appropriate foundation upon which to set my subsequent posts: the deep-seated desire I have to feel God’s presence in my life. Working on this post showed me that God’s presence is evident; I must simply orient myself toward it. Although the readings where jihad was discussed did not define the concept as an attempt to move closer to Allah, but rather as the pursuit of justice, I found the process of seeking out light to be incredibly healing for my marginalized body. I felt protected by Allah’s light, and the quiet places in which I found it. Most of the readings we had that discussed jihad related it to external relations (with family, society, corruption); some mentioned the fight against the ego, but I simply wanted to return to the root of the word as Asani does in his book: “j-h-d, meaning ‘to struggle, to toil, and to exert great effort’” (82). While I did not feel that I exerted the greatest effort to see this light (it was everywhere I looked on some days), it was on days when the sun did not emerge from behind the clouds that I had to search hardest. The struggle manifested when the conditions for the search did not appear to be met. Jihad for me is now about the search when so little appears evident.

That spiritual search is one I have been continuing for a while now, but one that became much more personal with an encounter I had at nineteen, during my first visit to Paris. While there I met a man in all white garb, who gave me his prayer beads upon seeing that he had none to sell me. I remember being overwhelmingly moved by this gesture of kindness. To this day, I believe that I saw all of what Islam is in his generosity. While this was a beautiful moment in which I saw a shining example of Islamic practices, it is also the point in my portfolio at which gender begins to play a larger role. My interactions with the man were laced with a fear that he would reject me on account of my outfit and my body—a sentiment I struggle to believe would define the experience of a man entering any mosque. Learning about women such as Rabia al Basri reminded me that my feelings were in many ways scripturally ill founded because a generous Muslim (like this man) would not reject me on the basis of something as superficial as an outfit.

My third post took on a different medium: this time I attempted to tackle gender in a sonic sphere. We discussed in depth the ways in which the likes of Rabia sought a path toward Allah that was not shaped by the bifurcations of “halal” and “haram” that lead individuals to count their attributes in a manner that reifies the materialism they claim to denounce. While we had not read the works of Benezir Bhutto, Nawal el Sadaawi, or Amina Waduud, I still identify with their assertions about patriarchy that we discussed in lecture. When I first began searching for pieces on the Sama’ rituals, all the videos showed men as whirling dervishes. I appreciated the very apparent interiority they were clearly experiencing, but I wanted to see a woman embodying that same search for divinity. I found a Sufi meditation video of a woman repeating the words “La illaha illa allah” There is no God but Allah. While I am not entirely sure how much I succeeded in augmenting her voice in the track I produced, I wanted to center her nonetheless as a moment of retrieval. In the month or so since I made that track, I have regularly listened to it—also in an act of spiritual healing for myself—as a reminder that my religiosity also matters.

For some time after that post, I struggled to find a way into another artistic outlet. I had decided after my first post that I wanted each entry to be in a different medium. At this point I had produced a song, a photo series, and a brief memoir piece. I was not yet sure how to move forward, but our discussion of the varied forms of the ghazals left me inspired to attempt one myself. Since I majored in English as an undergraduate student, I had to extensively study English sonnets. I wondered if it would be a successful attempt to bring together the sonnet and the ghazal. While the sonnet allows for enjambment in ways the ghazal does not, the latter also allowed me to create a rhythm that would not have been possible with the sonnet due to the ABAB CDCD EFEF GG rhyme pattern. In this poem, I explore for the first time in this portfolio my habit of turning toward my Western peers for a precedent of blessedness that is not actually appropriate to my individual journey.

Similarly, reading The Conference of the Birds also challenged me because each of the birds, though their stories obviously differed from my own due to different contexts, they had similar impasses to me: egotistical, faux fear, a love of tumult, worldliness, greed. The hoopoe’s response each time reminded me of my humanity, and of the mental gymnastics I can put myself through in order to believe that I am simply not prepared for Allah’s love. The hoopoe’s frustrations showed me that this itself was actually an excuse and not a noble performance of modesty. Working on this illustration showed me that I tend to see in gray on most days because I cannot accept how intensive the work of loving Allah is. It would mean trying to see the light and the color at all times, but how much can my eyes and heart actually take? The Conference of the Birds remains a vibrant reminder, a beautiful standard of the ever-further horizon I should always reach toward, but will always be just that: a horizon. Still, just like the light, it is worth the effort.

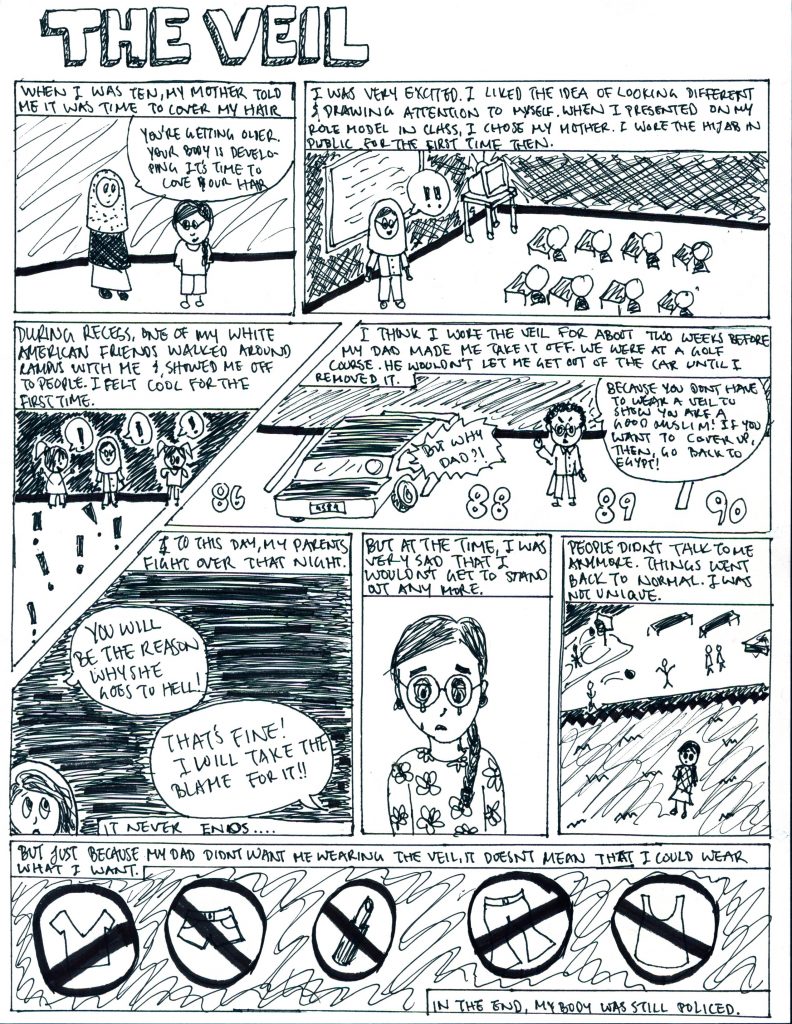

My final portfolio entry is a return to the worldly, which is—whether I accept it or not—where I am right now. Alas, I may reach to Allah all I want, but I am still on this planet. Marjane Satrapi’s comic memoir was a beautiful example of how personal narrative, diasporic identity construction, religion, humor, illustration, and evocation can all be rendered in a slim volume. I was deeply moved by the multiplicity encompassed in the worldview of a young girl simply attempting to navigate her worth and interests in a society that had reduced her to her body. As a woman, I have struggled with this on several fronts: whether as an Egyptian, a Muslim, or an exoticised person of color living in the West, I never go a day without feeling objectified. I also struggled, as I mentioned, to conceive of myself in a way that does not center Western images of liberation. I still do. I still have these questions, and my goal with this post was to open that door and let the pain flood through. I need to learn how to sit in the space where unanswerable questions are offered, where they permeate the atmosphere, and where I can breathe them in knowing that Allah will take care of me.

Persepolis was an appropriate way for me to finish this portfolio because in the end I am left with this politicized body, on this earth. I must accept that. Though this class is over, I now have the toolkit to ask myself questions about the obstacles placed before me and my relationship with Allah. With all the localized interpretations of Islam we have witnessed I have learned of the infinite ways in which one can be a Muslim. Though we can come together at times, to celebrate the Mi’raj, or Ramadan, or to pray Jummah, or to turn to the sky on Laylat al Qadr, we all go our separate ways, and we must turn inward. When we turn outward, I have now learned that we have to ask “Whose Islam?” In my case, I now have enough grace for myself to say that my Islam is just that: mine.