I was incredibly inspired by the simplicity, yet profundity, of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. Nothing she writes is laced with academic vernacular, and yet I felt a deep connection to her story. Her poignant characterization of her family and her own upbringing in Iran showed me how growing up in a changing society is categorically political, even when one is simply attempting to cultivate a sense of identity. Still, young Marjane is a denim jacket loving, Nike-wearing, communist girl full of wit, mischief, and hustle.

I identify with this young Marjane, but I am also in many ways, more similar to the Marjane who wrote this book: I, too, have to construct my identity from a distance. The older I become, the more I face my socialization in the States. As someone who has been marginalized in the US context for being a brown Muslim woman, it’s hard for me to believe that I am “American.” I tried to address this with the strip called “Egypt.” (Just as Satrapi does, I use particular objects and places–like the veil and alcohol–to propel my narratives). In the final panel, I am looking at a map, something I do often, and pining for a land that has also not opened its arms to me.

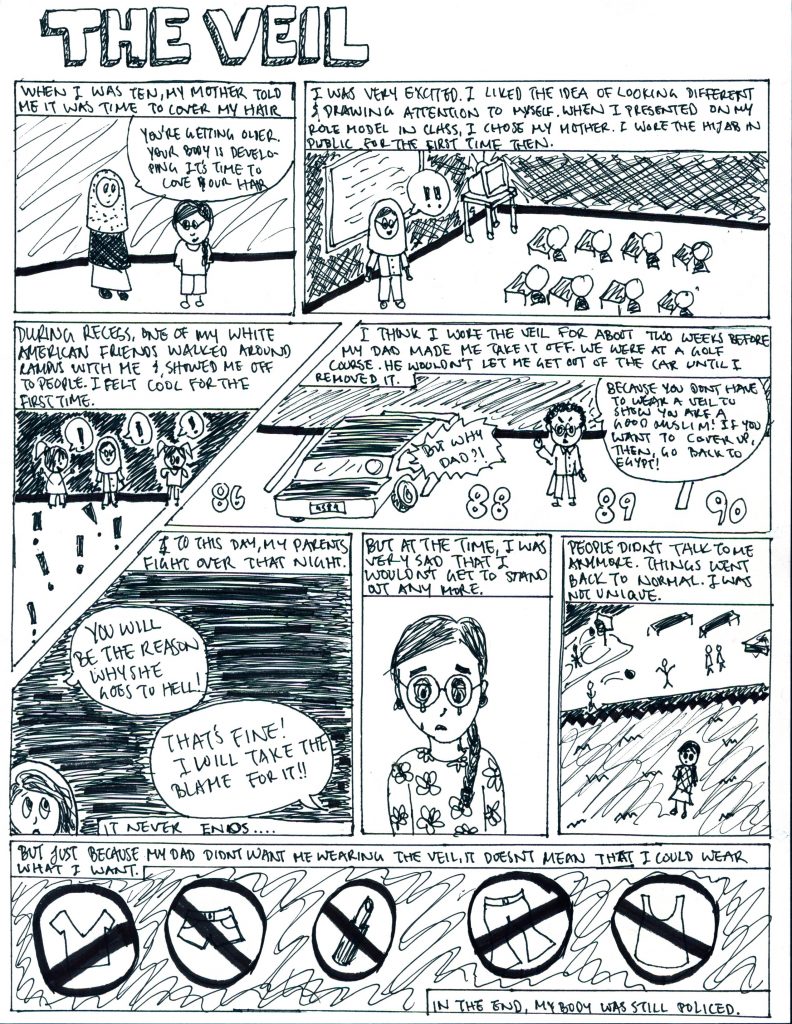

My relationship with the veil is different though because I recall being very excited to wear something that drew attention to me. I felt deeply invisible all throughout grade school–a sentiment that germinated during my final years of elementary schooling. This was when my mother said I needed to begin covering. I liked the idea of standing out, of being different, but my father saw the political and social ramifications of such a difference as too risky. He made me take off the veil, but still punished me when I wore things that he saw as too Western. Again, I felt as if I was straddling a strange place: no veil, but no Western clothing. For the most part, I am a modest dresser, but my father’s policing of my outfits throughout middle and high school also showed me that what I wear is incredibly political, and cemented the idea in me that my body is inherently sexual–a notion that has also proved dangerous and difficult to unlearn.

Finally, the comic entitled “Boys and Booze” also speaks to my failed attempts to Westernize. Like Satrapi, I was in some ways enamored with Western culture. I too wanted the shoes and the jackets that would make me feel “cool” like my classmates. Ultimately, this hurt me, as I realized this desire was rooted in a worldliness that did not have faith in Allah’s love for me. Today, I am still confused, lost, and misguided in many ways, but my past experiences act as markers of growth and learning that mirrored many of Satrapi’s account.