An Introduction and Thank You

Nearly four months ago, I came into this class knowing close to nothing about Islam, except for the minimal that I had to know to understand international relations during high school. The seminar has not only been rewarding in the content that I have learned, but the people I have met, and the friends that I have made—I genuinely think what I learned from the people in this class and the perspectives they had to share was something I could not have learned from reading any book.

We started off the year by discussing world views, and Professor explained how he wanted this experience to not just be a chance for us to learn more about Islam and read literature by contemporary Muslim writers, but to understand our own and others’ worldviews in a deeper and more conscious way. Just as the stories that you were told as a child changed your world view, the stories that we tell each other now have the potential to change one one another. I think that is the reason stories are powerful, and why we started off each class by telling stories. As my classmates pointed out to me during one of your discussions, only with more narratives can we overcome bigotry and misunderstanding.

During the first class, we also talked about the elephant metaphor; everyone touches a part of the elephant—in this case comparable to Islam—with a blindfold on, and mistakes the part that they feel for its entirety. Is it a tree? A sofa? Is it violence or peace? Progress or backwardness? As we have discussed since then, one brings to Islam one’s own worldview—a combination of cultures and preconceptions—that make my Islam different than your Islam. Furthermore, Islam is neither peace nor violence; it’s a religion. Predisposed to nothing, the different interpretations that each person brings to the faith determines its manifestation. That is why a nationwide sentiment unfavorable towards Islam does not make sense because it pits a country against a religion; finding a scapegoat to foster nationalism is not only unfair to the minority group that it preys on, but dangerous as to the implications that it has on the morality of human dynamics. Must we always have someone to blame to promote unity?

At the end of the day, to reach the cosmopolitan world that the Aga Khan spoke about here at Harvard, we must do more than merely co-exist with one another. With co-existence comes a responsibility to listen to each other’s stories, understand each other’s differences, and ultimately, grow to love and celebrate diversity. However, I also think this process can be achieved in the other direction, and gives hope to the elimination of the prejudices that are globally salient today. When one forms a relationship with another person on a human level—regardless of differences—and becomes friends, one will inevitably get to know the other. With globalization, it is becoming increasingly easier to talk to people from all over the world, and form relationships with them. However, as the Aga Khan said, there is much communication these days, but no genuine contact. Still, I think as long as one is genuinely open when forming relationships, it is impossible to further the othering of the group s/he belongs to. As it says in the Korean quote that I mentioned in one of my reflections, only when we love will we know, and only when we know will we be able to see with clarity.

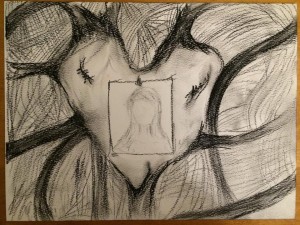

On a different note, I particularly enjoyed all the exposure to poetry and songs throughout this seminar. I think there is something beautiful about a people who originate from wars fought in poetry, and likewise, there is a sense of deep-rooted beauty in the poems and hymns that can only come from long tradition. I agree with Professor Asani that art and music are both closely tied to spirituality, which explains why many are exposed to religion through those means. A common basis for most human experiences, art and music allow for a special kind of connection to ones emotion or existence for a fleeting moment, one that cannot be described or recreated in words. I also think the arts are a great way for individuals to be introduced to other communities. Only when one can understand another’s prayers, will one be able to imagine the other complexly.

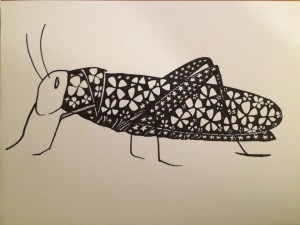

I know this is really redundant, but I am going to mention it anyways because it is still very important to me: I think the most important thing we can do in life is to imagine every person we encounter as a person. This goes from an individual level to a community level as well. Imagining people or communities complexly does not mean purposefully ignoring flaws and packaging them up in false idealistic labels. Rather, it means that while we consider the grasshoppers, we also remind ourselves of the existence of the jasmine and the stars.

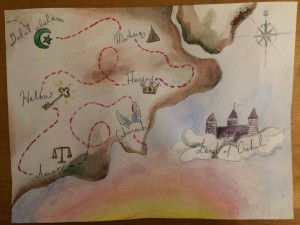

This has come up in a class discussion before—does focusing on the jasmine and the stars mean that we do not give the grasshoppers the attention they deserve? Does it undermine the severity of the grasshoppers and their effects on society? Ideally, I would like to say no. I think both jasmines, stars and grasshoppers are necessary to know Pakistan—actually, you need to know a lot more than those three to know Pakistan, but you know what I mean—and see that even if there are problems, that does not mean there aren’t also living human beings who have the same daily concerns as we do. Humans often have a habit of reducing the people suffering from problems in far-away locations to just problems. The danger is this taking of humanity can be seen in all the inhumane and immoral policies (or lack thereof) that have been implemented globally. Also, this might not be totally on topic, but I would like to quickly share a quote with you by Doctor Paul Farmer: “The idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that is wrong with the world.”

It is impossible to describe the progression of my understanding of Islam in this class without mentioning Iqbal. I know that emphasizing my revelation when we learned about him only sheds light on my prejudice towards religion up to that point, but nonetheless, it is true so that’s alright. For me, the idea that Islam stands for progress was mind blowing. Since I was younger—perhaps 14 years old—I had decided that religion at its best can be a comforting factor and moral inspiration for some individuals, but that usually, it is the underlying cause of stagnation in social and societal development, and that it only supports archaic beliefs and practices. This might have had to do with my lifelong schooling in the Catholic education system. Although when I came into this class I thought I had removed such preconceptions from my head—evidently so because I wanted to take a freshman seminar about religion—I guess I had failed to do so completely because when Iqbal’s interpretation of Islam being a faith of self-growth, and ultimately societal development and co-creation with God clicked in my head, I felt like I had reached some kind of epiphany. (Also, I think we might have to take into consideration that I was probably emotionally charged from a. an amazing class as per usual and b. Iqbal’s beautiful poetry.)

In case you don’t read my other posts, here are the lines of poetry that caused such an uproar by me at the end of and after class that one Tuesday night:

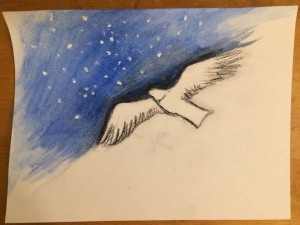

“Beyond the stars are other worlds

There are still more tests of love

You are an eagle, flying is your occupation

There are yet other heavens before you.” (This is also the subtitle of my blog…)

There were many other things I learned in this class that challenged my (shameful but true) preconceptions of Islam from before. For example, the variation of women’s rights and freedom depending on interpretation was fascinating. In fact, I think some of the authors that we read books by had fairly progressive lives, and I remember that one of them was pushed by her husband to study more. Furthermore, the last background reading that we had to do for the concluding lecture was interesting in its defense of homosexuality in the Qu’ran. Since the Qu’ran makes no direct reference to the categorization of homosexuals nor any specification that women must wear hijabs, these interpretations all hold valid points. This still confuses me because I do not yet know the main interpretations that are widely accepted of the Qu’ran. I still have much, much more to learn about Islam, and I am glad I was introduced to its studies through this seminar.

Finally, I would like to say that I honestly thought it was some kind of sign that I had the honor of taking this class this semester in particular. Firstly, many topics that arose in this seminar overlapped with concepts that I learned about in my History of American Democracy class—perhaps not blatantly or directly, but enough that I could make connections, and feel as though the universe cared about my education. Secondly, with controversies about the Republican primaries, the Paris terrorist attacks, the Syrian refugee crisis, and the overall tension concerning Anti-Islamic sentiment that came to its zenith a couple of weeks ago, I was beyond appreciative to have this class to go back to for feed back and reassurance every week. Without this seminar, I don’t think I would have had the vocabulary to articulate my frustration with what was going on, and the moral support I received from just listening to similar feelings from my classmates and as always, the calming and helpful explanations from Professor Asani, gave me the courage that I needed to maintain my hope for humanity. All of these things fit together so perfectly for me, and for the first time in a very long time, I felt taken care of and not alone in my worldview to a point that I honestly think applying for this seminar, meeting Professor Asani, and taking it with my eleven other brilliant classmates was a gift and a sign.

I am not particularly religious anymore (or at least, not for this moment in time), but I do think I am a spiritual person. I don’t necessarily think things happen for a reason, but I do believe it is important appreciate the beauty of coincidence, and to be grateful for the universe’s grace when it grants me such beauties. If you are still reading this, thank you for being a part of FRSEM37, and thank you for making every Tuesday of my first semester of Harvard a day to look forward to. Best wishes for you in everything that you do, and as the Korean saying goes, may you and your loved ones only walk paths of flowers and blessings.