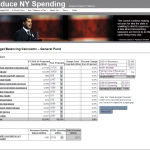

Nancy Scola of TechPresident recently excoriated a budget calculator put out by NY Governor Patterson, primarily on the ground that it’s “more a dull-edged hatchet than a scalpel” and ignores revenue options. Strangely, though, she ignores the glaring fact that the tool is painfully meaningless to any normal taxpayer. Never mind how ugly it is (though that matters); its numbers are not only grossly general but also inhumanly abstract.

Nancy Scola of TechPresident recently excoriated a budget calculator put out by NY Governor Patterson, primarily on the ground that it’s “more a dull-edged hatchet than a scalpel” and ignores revenue options. Strangely, though, she ignores the glaring fact that the tool is painfully meaningless to any normal taxpayer. Never mind how ugly it is (though that matters); its numbers are not only grossly general but also inhumanly abstract.

Scola also mentions the Obama-Biden tax calculator, which presents an interesting contrast. It, too, is a calculator — raw numbers stacked up — but it has the distinct engagement advantage of being about your money. Its designers don’t need to provide context or background; presumably, you know exactly what another $1,000 in your pocket would mean.

Such lame attempts at public education (or, as Scola argues, “pretend participation”) ignores the basic problem that for most taxpayers, issues of government taxes and spending are emotional, not rational, and not because we are innumerate but because such systems are too big and too remote for most of us to comprehend. This is a point that Prof. Henry Jenkins makes in his essay, “Complete Freedom of Movement,” which contrasts the play spaces of boys and girls. Whereas a game like Sim City allows players to mold physical territory, in girls’ games and stories like Harriet the Spy “the mapping of the space was only the first step in preparing the ground for a rich saga of life and death, joy and sorrow – the very elements that are totally lacking in most simulation games.”

Stated differently: cutting $10M from the state’s Department of Mental Health means something real for real human beings. The essence of a true public policy debate is to capture human reality in the discussion, not abstract it into numbers. (To those who argue that this would merely lead to an exploding debt, it’s up to deficit hawks to describe the issue as compelling drama, not formal logic).

A different contrast can be made with the Massachusetts Budget Calculator Game, Question 1 edition. As in the original version of this spreadsheet game, each top-level line item is explained with ample text — which requires players to be both numerate and literate. This “game” is no better than Patterson’s effort — except that the point isn’t really to balance the budget. The point is to show just how absurd repealing the budget is. It turns out that it’s pretty much impossible to eliminate the income tax without destroying practically all of the Massachusetts government, which an overwhelming majority of voters ultimately agreed was reckless. Rhetorically, then, the Globe’s budget game was less a simulation and more an exercise in futility, much like the message embedded in Ian Bogost’s “editorial games” for the New York Times.

A different contrast can be made with the Massachusetts Budget Calculator Game, Question 1 edition. As in the original version of this spreadsheet game, each top-level line item is explained with ample text — which requires players to be both numerate and literate. This “game” is no better than Patterson’s effort — except that the point isn’t really to balance the budget. The point is to show just how absurd repealing the budget is. It turns out that it’s pretty much impossible to eliminate the income tax without destroying practically all of the Massachusetts government, which an overwhelming majority of voters ultimately agreed was reckless. Rhetorically, then, the Globe’s budget game was less a simulation and more an exercise in futility, much like the message embedded in Ian Bogost’s “editorial games” for the New York Times.

But what about a game that actually helps the player understand a budget and make difficult tradeoffs? Possibly the best example out there is Budget Hero from American Public Media. (Read Ben Medler’s review). Among its stronger features is the ability to choose particular values that your budget should maximize (e.g. “national security” or “energy independence”). As your budget fulfills those values, the corresponding “badge” fills up. It’s a relatively elegant way to convey the idea that budgets aren’t just abstract numbers but expressions of our collective social values — moral and meaningful choices writ large. It also doesn’t hurt that the design is colorful, noisy, and generally attractive.

But what about a game that actually helps the player understand a budget and make difficult tradeoffs? Possibly the best example out there is Budget Hero from American Public Media. (Read Ben Medler’s review). Among its stronger features is the ability to choose particular values that your budget should maximize (e.g. “national security” or “energy independence”). As your budget fulfills those values, the corresponding “badge” fills up. It’s a relatively elegant way to convey the idea that budgets aren’t just abstract numbers but expressions of our collective social values — moral and meaningful choices writ large. It also doesn’t hurt that the design is colorful, noisy, and generally attractive.

Most intriguingly, Budget Hero also compares your results with peers (assuming, as Medler points out, that the players are truthful). It’s a step in the right direction towards an engaged and informed public dialog.