I came to this class late. The day I joined was the day that a major project was due; we had to write “Allah” in Arabic, through a creative medium. Faced with now producing a sophisticated piece of art that my classmates had weeks to consider, I paused. Ultimately, I photographed pens in the shape of the word—in a sort of “meta” reflection on the pens’ importance in visualizing “Allah” through intricate calligraphy. I don’t know if it was very good. But it was the first time that I had encountered a class leaning on art as a pedagogical tool to understand—and build on—the concepts explored in a lecture. And it was a curious and refreshing overhaul of a teaching style that dates back to ancient Greece.

After three months, we have not tried to understand Islam. We have learned how to understand the world’s second largest religion. We have learned that the heart of the religion is not in scripture—that’s the mind, so to speak. The heart of the religion is its culture, and it beats with astonishing vivacity in its aesthetics. It beats to the rhythms of Urdu ghazals and it is nourished by stunning architecture in its mosques and it pumps meter and rhyme in its poetry. We learned that we could read the Qur’an, reflect on the five pillars, but to understand what it is to be a Muslim is to go far beyond the literature. It is to understand how a Muslim engages with the religion, through her culture and daily routine.

That was the first lesson. Since then, we have broken up the massive body of information that exists to answer the question of what it means to be a Muslim. Through a systematic piecing up of our responses, we learned we can begin to visualize an absolute answer. And so we learned to appreciate the diversity in the answer: Not to run from different answers, but to see how they correlated and was part of something larger, something bigger. We understand each different experience to pull together a more global understanding of what it means to be a Muslim. In this process, we varied over different processes, including looking at variations across politics, age, literature, persecution, and visual art. We have roamed the world in learning about the incarnations of Islam in different countries. We traveled to Saudi Arabia, Czechoslovakia, Iran, Pakistan, and America, among others. And in each country, we have seen a variation of what we might assume is an “absolute.”

Islam offers more than a typical religion. With sharia law, and Muslim legal experts who specialize in religious jurisprudence, the religion is uniquely sophisticated. Perhaps as a consequence, Islam is a joy to behold in its diversity of adoption in governance by different regimes around the world. The politics of Islam is often portrayed in international media. Perhaps most recognized is the clash between Islam’s tenet that women must wear a hijab and the Western, 21st century notion of “modernity” and liberalism. The even especially came to center stage recently in France. During the affair, young women who were French and Muslim attended their public schools wearing a veil. Teachers, principals, other students and their parents—they all rebelled. They claimed it was an insult to the freedom of rights that France upheld. The Muslim community shot back, holding up freedom of religion as a powerful counterargument. The debate sizzled and charged a polemical debate: By wearing the hijab, were these young women compromising their own freedom or by not allowing the headdress was society compromising their rights to express their religious faith. But while this development played out on an international stage, other debates have been more local to national governments. Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis was a fascinating look into two extremes of Islam. Her family, a left-leaning, liberal household, is Muslim. Under the new regime of the Ayatollah, her family is forced to change. Marjane adopts a veil to go to school. And further we explored the definition of Muslim though Michael Knight’s own journey of who he is and what it means for him to be a Muslim.

At some point in our lives, we are told our names. Sometime later, we are often told our religion: whether Christian or Hindu, Jewish or Sikh. For many of the characters we met during the semester, we observed their interactions with this truth—or how they attempted to change what they were told to what they knew. Satrapi’s story goes beyond how her interaction with how surroundings influence her religion. Persepolis indeed rises to be a powerful tale of how she negotiates her rearing as a Muslim with a new, fundamentalist regime. In the sequel, she would face larger difficulty in handling her natural inclinations with the new world of Europe. Sardar’s tale was similarly transporting. He begins his story, Reading the Qur’an, discussing the soothing lyricism that hearing the text would provide him, as his mother would read him the book. As he grew older, went to a religious school, he aged, and his interpretation of the literature changed. He began exploring the depths in the chasms that exist with frequency in the literature. For Sardar, the text provided him with some sense of added purpose and questions. These two characters grew up with Islam—grew up Muslim. Knight’s tale is a different one. He tells us how he became a Muslim. With this later entrance into Islam, Knight recounts how his definition of what it meant to be a modern Muslim often would clash with others.

Nearly as diverse as the geography in which the religion spanned, the body of artistic literature that Islam includes is vast. We can see a variety of poems, most notably the ghazal. It is more individual to Pakistan and the Urdu language, and it carries a very distinctive meter and a rhyme scheme. The repeated word at the end of each couplet is perhaps the most individual characteristic of the poem. Indeed, like its cousin of the maulud, the ghazal often leans on a doleful tone to motivate the piece. In the maulud, the poem relies on greater specificity. The narrator calls longingly for a separated lover, often male. It is assumed that the narrator’s pangs are more or less fruitless. And the ta’ziyeh provides another remarkable literary point for the religion. Less a manuscript and more about the performance, the ta’ziyeh is a remarkable symbol for the presence that art has for Muslims—and not just those with higher levels of education. The play follows the persecution of Hasan and Husayn, members of the Ahl al-Bayt. It is a popular play, and in the class, we saw a rendition in the villages of Iran. For them, this level of aestheticism is vital to their spirituality. And if they find either ghazals or mauluds inaccessible, they will at least be able to rest on the ta’ziyeh for providing rich, tenable content.

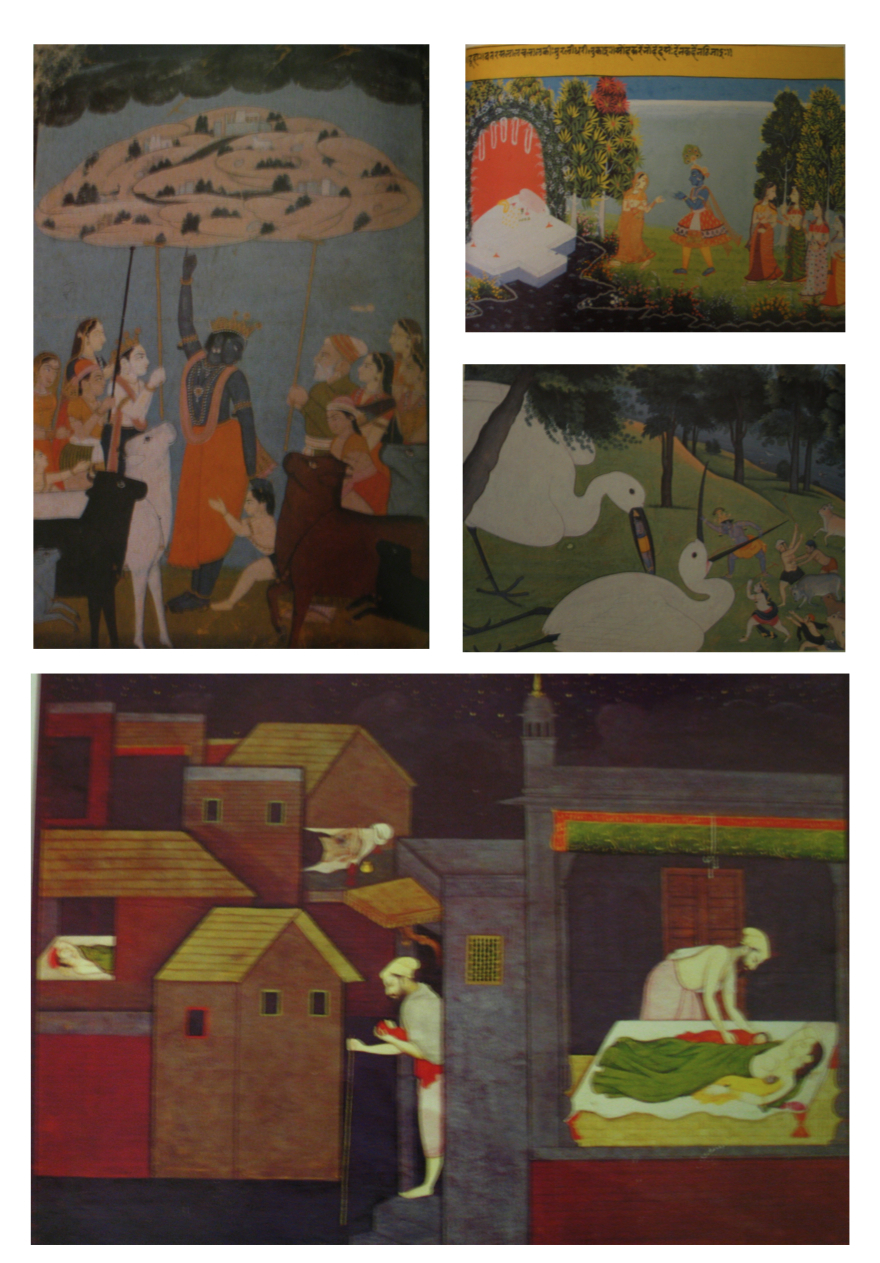

Indeed, the ta’ziyeh might even fit into the wider field of visual arts, another rich body of aesthetic work that has defined much of the culture. Here we even see some very universal approaches to visual art: as it is forbidden to draw God or his Prophet, many Muslims rely on the names, heavily caligraphed, as a form of divine art. The delicate strokes and captivating calligraphy even translates to those practicing Islam in Chinese sects. We have also seen stunning miniature paintings that have been central to the culture of Islam. Indeed, in India, these paintings went beyond providing a source of rich culture for many Muslims; they also created a strong backbone for much of the artistic creativity in the nation. Miniature paintings were adapted to capture scenes from Hindu texts, such as the famous epic, the Mahabharata. This embrace of a new religion by its culture is in fact a fine representation of the culture that Islam creates: the culture is not necessarily defined by the religion but by the principles it stands for.

Lastly, persecution provided ample material. The idea of persecution predicates much of the Shii sectarian beliefs system. As dramatized in the ta’ziyeh, Shiis do not look favorably on the Saudi caliphate, casting aspersions on the ancient kingdom for its slaughtering of the royal Ahl al-Bayt family. But persecution was not isolated to ancient times. In a post-revolution Iran, the nation was besot by persecution, as fundamentalists elements pulled on the same mechanisms to create terror that the caliph did so many centuries ago. Further, the western perception of persecution of personal rights is one that is interesting to examine by trying to be on the side. To what extent is wearing a veil a persecution of personal rights or a freedom to express oneself? These ideas certainly informed the religion—both in days past and days present.

The semester was a stunning whirlwind into the lives of Muslims around the world and the art that they enjoy. I may have joined late, but I am happy I joined.