Moving venues, already

December 25th, 2009 by GrahamHowdy.

I’ve moved this blog to another server for more flexibility. All of the existing posts have been moved over, and comments here are closed. Please visit:

Understanding the Internet and global political change

Howdy.

I’ve moved this blog to another server for more flexibility. All of the existing posts have been moved over, and comments here are closed. Please visit:

Via @berkmancenter, an interesting-looking conference at the New School, Feb. 24–26:

The central question asked by this proposed conference is, where is America today with respect to the limits on our access to information, limits on what we can keep confidential and what the government and other institutions can keep secret? How can the public gain access to information and how do we decide what information is a citizen’s right to know? What information endangers individuals’ or the country’s wellbeing and safety? Are the ever-increasing number of technological innovations fundamentally transforming what we can know and what we cannot? What can remain confidential and what cannot? On the one hand, technology has aided access to information and knowledge to broader and broader communities, thus eroding limits, while on the other hand, technologies are increasingly used by governments, businesses, and other social institutions to monitor and interfere with what we can know and cannot know and what is private and what is not.

An interesting array of speakers. Bios here.

Tim Hwang has a remarkable essay looking at what he’s provisionally calling “The Berkman School of Thought” based loosely upon the community surrounding the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard. The original post is a must-read. He proposes four pillars of Berkman School thought:

I started writing a comment on his post, but it got lengthy, so here we are.

There is probably a lot that can be said on the topic of a “Berkman School” and its relationship to cyberoptimism. Hwang notes that many Berkmanites tend to be optimistic about the Internet’s transformative potential, but that notes of caution sometimes emerge, as from Ethan Zuckerman and Eszter Hargittai. I might add Rebecca MacKinnon to that list.

I’m curious about two things.

One is how we might understand other “schools” of thought on Internet and society. Certainly many others could be suggested. There is a problem, however, in looking for groups of thought on the Internet in that many of the non-Berkman-type perspectives are rooted not in discourse directly about the Internet but rather in academic disciplines, policy communities, or business communities.

When political scientists, sociologists, or policy scholars take to understanding the Internet and society, they bring their communities’ theoretical contexts into play. Carving out schools might be easiest if the criteria for delineation are assumption-based rather than content-based. I think this is what Hwang is on to when he talks about “faith” in various principles. But if those are the principles, MacKinnon’s work on “cybertarianism” and Hargittai’s work on web-use divides and socioeconomic status, for example, might tend to put them farther from the Berkmanite epistemic community, despite their personal affiliations with the center.

Moreover, Benkler’s work reaches out toward social and economic theory while also engaging with the particular story of the Internet.

Two is how US- or democracy-specific are these assumptions, and to what extent the center’s physical home at Harvard Law School affects some of these assumptions. Many participants in this line of thought are not American, but that doesn’t remove the fact that freedoms, free speech, and liberal democracy seem to be key motivating factors. I think this is similar to what commenter Jillian C. York mentions at Hwang’s post.

This is important because many Berkmanites are activists as well as thinkers. In political terms, many of these projects, their coordinated action, and their claims making vis à vis various business and government bodies could mean it’s most reasonable to think of a Berkman School as more of a Berkman-like movement. Without rambling on about the ties between schools of thought and political movements, I just thought that would be an interesting thing to point out.

I hope this discussion continues.

I’m going to be blogging notes from this talk by David Weinberger at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard. Usual caveats apply (all things not in quotes paraphrased, sometimes badly.) Here we go!

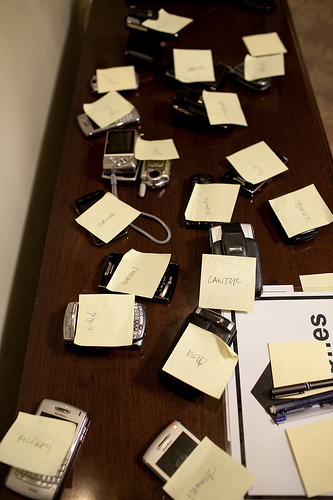

I don’t want to overstate anything, as a cursory Google search offers no confirmation, but from the looks of this photograph from the official White House Flickr feed, sometimes having a meeting in the Oval Office means checking your tech at the door.

The official caption reads: “Cell phones are left outside the Oval Office during a meeting with President Barack Obama, May 25, 2009.” As commenter clareperretta points out it would be fun to know what the little card on the table says.

The Flickr account itself is pretty cool. Not quite Hugo Chávez’ Aló Presidente, but it’s part of some interesting things the present administration is doing with online publishing.

UPDATE: Even if you’re an important member of Congress, you leave it outside. This image from outside the cabinet room.

Wired reports: “The Justice Department, citing anti-trust and copyright concerns, asked a federal court judge late Friday to reject a controversial settlement that would have allowed Google to cut through knotty copyright issues in order to create the library of the future.”

The Justice Department’s concerns mirror some of the sentiments expressed by Harvard law professor John Palfrey when a seminar last spring took up the settlement. As the wiki record of that week notes, Palfrey suggested improvements to the settlement that would allow the immensely valuable resource to come into existence without hurting the prospects for future innovation.

Professor Palfrey suggests three generalized improvements to the settlement that would begin to address many of the concerns that have been raised:

- Ensure the possibility of a meaningful competitive landscape, such that second-comers are not barred from success.

- Establish a means by which the public can have a meaningful level of control over the workings of the Book Rights Registry.

- Create a system of periodic review for the settlement terms. This system would not need to involve periodic wholesale review of the entire settlement by the courts; it could instead merely involve libraries negotiating sunset provisions for individual works with publishers, authors, and other rights holders.

As a researcher, I have already found the Google Books machinery to be of great use. I have used it to access sources I did not have space to bring along while studying in Beijing last summer. I have used the full-text search available for some texts to double-check citations when preparing papers. And I have been able to point friends and family to specific passages of books without scanning or retyping the text by hand.

My additional hope is that the restrictive provisions in the settlement that regulate how the data can be used can be avoided at the library terminals that form part of the public good derived from Google’s gargantuan scanning project. If the vast amount of information being gathered can be processed in yet unforeseen ways, computation-based research may reveal hidden value in a corpus of text. If we are restricted to search and display applications that replicate traditional reading, however, we will still fall short of the potential this information holds.

In recent months, blogging has taken a back seat to other writing in my life: seminar papers, course assignments, and yes, even letters. Sometimes, however, I stopped short of writing because my present blog space at Transpacifica isn’t the right place to put musings on Internet research and information in politics. That brings me here.

Why write here rather than on my own site? It’s about community. The Berkman Center, which provides this forum, is a convivial and diverse collection of scholars, engineers, and activists, many of whom I have had the chance to meet or learn from. Many of them write here, at blogs.law.harvard.edu. I only hope I can contribute something to the lively discourse in progress among this community’s other blogs.