Modern Books and Manuscripts and the Reese Sale

Mar 8th, 2023 by houghtonmodern

The online auction of The Herman Melville Collection of William S. Reese, September 1-14, 2022, was eagerly anticipated in American Literature research circles, library special collections circles, and trophy-hunting collecting circles. Results were impressive. The Christie’s sale realized nearly $3,000,000 for 100 lots, though not all were hammered down. There were sky-high bids for presentation copies of Melville’s works, annotated titles from Melville’s library, and letters in the author’s hand. Perhaps the most remarkable moment of the sale came, in overtime, when Melville’s heavily annotated copy of Dante, purchased in June 1848 for $2.12, went for $441,000.

Houghton Library’s Department of Modern Books and Manuscripts, which curates Harvard’s incomparable Melville collection, did very well in bidding at the sale, winning each of the six lots on which it offered. The department pursued archival additions to established research collections and individual items meant to round out existing strengths.

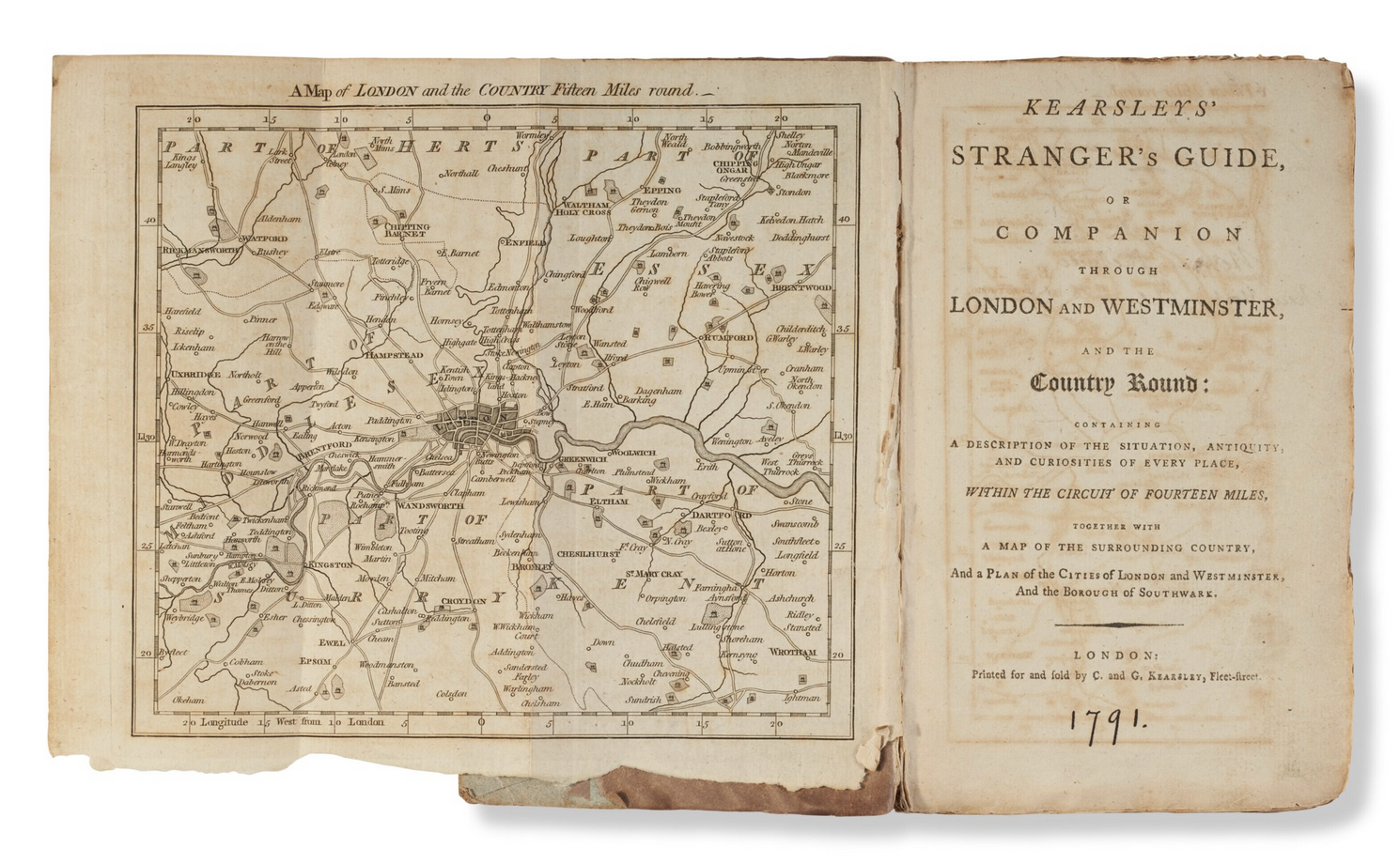

The library owns the largest collection of annotated books from Melville’s shelves, now adding to that number by acquiring lot 671, Kearsleys’ Stranger’s Guide, or Companion through London and Westminster, and the Country Round (London: [1791?]) (Sealts, Melville’s Reading, 304a). This family copy was first acquired and signed by father Allan Melvill in Paris in December 1807, and then by son Herman in New York City, July 6, 1850. Scholars have linked this long-held family volume to passages in Redburn (1849) and Israel Potter (1854).

Kearsleys’ Stranger’s Guide, London [1791?]. Credit: Christie’s

Kearsleys’ Stranger’s Guide, London [1791?]. Credit: Christie’s

Lot 665 consisted of a collection of Allan Melvill’s business and family documents, letters, manuscripts, and ephemera, 1801-1822 (in English and French). Allan failed in business in Manhattan in 1830 and retreated, discredited and deeply in debt, to Albany, the home of his wife’s family, the Gansevoorts. He died delirious of a fever in January 1832, leaving his widow and eight children, including 12-year-old Herman, his second son, in reduced circumstances. This collection fits nicely with other (sometimes grim) family business-related papers from the same period in the Houghton Melville Collection, while also documenting in detail the logistical and financial challenges, even in good times, of Allan’s fancy French goods import business.

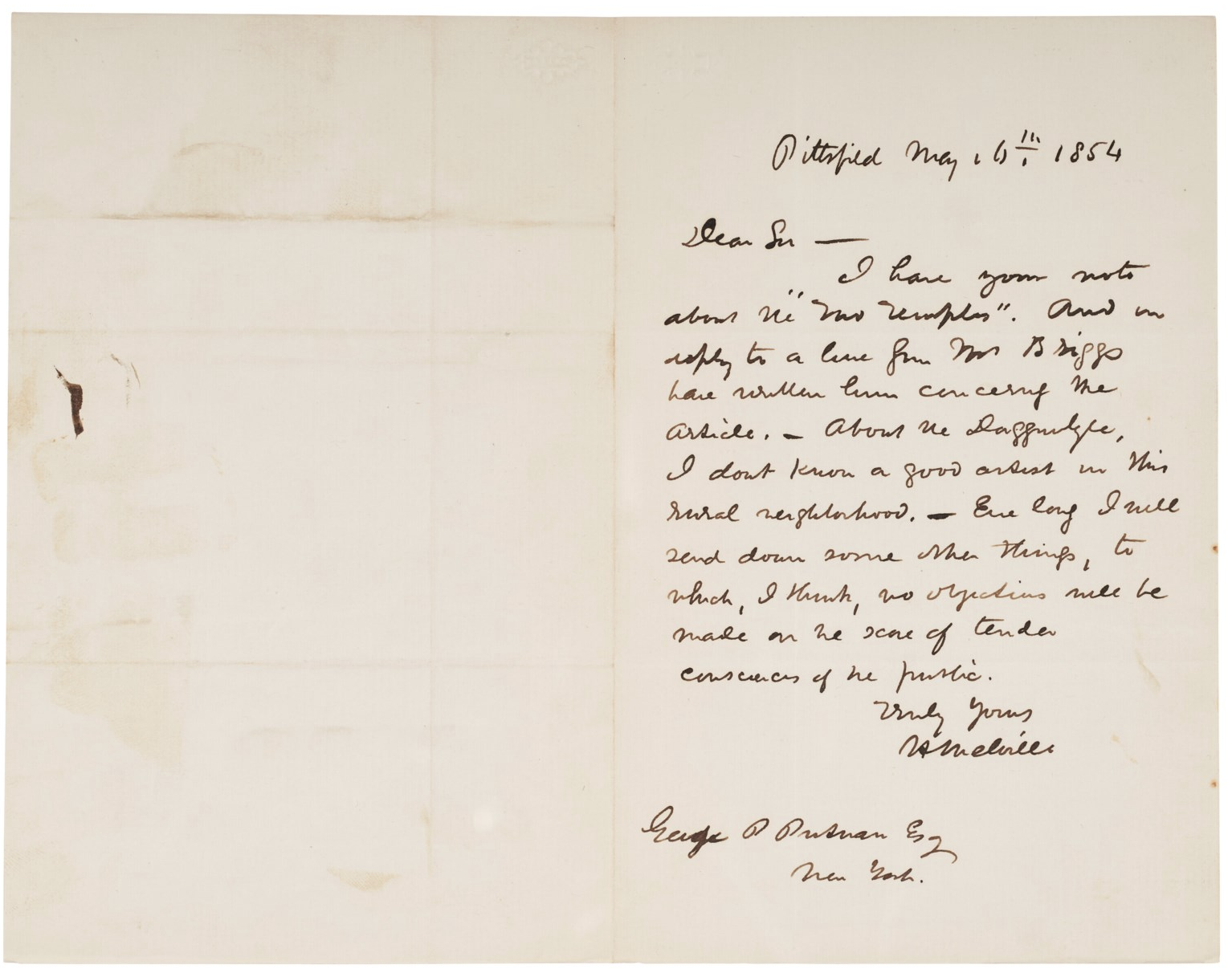

Lots 637 and 653 each offered a manuscript note from Melville to his publishers, and I won’t object if readers think that these notes document in detail the logistical and financial challenges, in less than good times, of a certain writer’s “export” business. Melville’s note to George Putnam, May 1854, acknowledges the rejection of his satirical sketch “The Two Temples,” dodges a request for a daguerreotype, and promises to submit “ere long” to his publishers some other “things” for consideration “to which, I think, no objection will be made on the score of tender consciences of the public” (the editor of Putnam’s had found Melville’s “T3” satire of Grace Church too “pungent”). Houghton owns the only known source for the text for “The Two Temples,” a fair copy of the two-part sketch in the hand of Augusta Melville, Herman Melville’s younger sister and frequent copyist/decipherist. The piece was never published in the author’s lifetime. The second note (“Pittsfield May 18th [1859?]”) is addressed to “Gentlemen” (presumably Harper & Brothers) and submits accompanying “short pieces” for consideration for magazine publication. The “short pieces” remain intriguingly unidentified; no work by Melville appeared in Harper’s or in any magazine in the late 1850s or early 1860s. The first note is published in the Correspondence volume of the Northwestern-Newberry edition of The Writings of Herman Melville (pages 261-262). The second note does not appear in Correspondence, though a similar note to Harper & Brothers does appear on page 336.

On the rejection of “Two Temples” and refusing to be photographed. Herman Melville, 16 May 1854. Credit: Christie’s

Curator Leslie Morris’s final success with Melville materials at the sale was the purchase of lot 691, William Clark Russell’s letter in 1893 to Edmund C. Stedman, the NYC “broker-poet” and Melville’s E. 26th St. neighbor. Stedman was also Melville’s occasional editor/correspondent, drop-by visitor, and reading material lender. In this letter Russell discusses, among other things, the reprintings of Typee, Omoo, White-Jacket, and Moby-Dick in 1892 (the year after Melville’s death), edited and introduced by Stedman’s son Arthur. Russell was also a fiction writer on life at sea, was Melville’s late-in-life British champion, and was the dedicatee of Melville’s privately printed collection of poems, John Marr and Other Sailors with Some Sea-Pieces, in 1888. Houghton owns not only the dedication copy of John Marr, inscribed to Russell, but also the correspondence of Melville’s widow, Elizabeth Shaw Melville, regarding the publication of those 1892 reprints of four Melville early titles.

All Melville purchases at the Reese sale were made with income from the Robert G. Newman (MA ’35) Library Leaders Fund.

The library’s non-Melville winning bid at the auction came on lot 697, Rockwell Kent’s manuscript journal and sketchbook from his travels in Greenland in the early 1930s. Houghton owns other watercolors by Kent based on these Greenland adventures. All but one other Kent lot in the auction was related to his work as an illustrator of Melville.

Parting advice to Melville enthusiasts: mark up your copies of Sealts and Northwestern-Newberry Correspondence accordingly, and start saving up commensurately for the next appearance of Melville’s Dante on the market.

Thanks to Dennis C. Marnon, retired Administrative Officer of Houghton Library, for contributing this post.

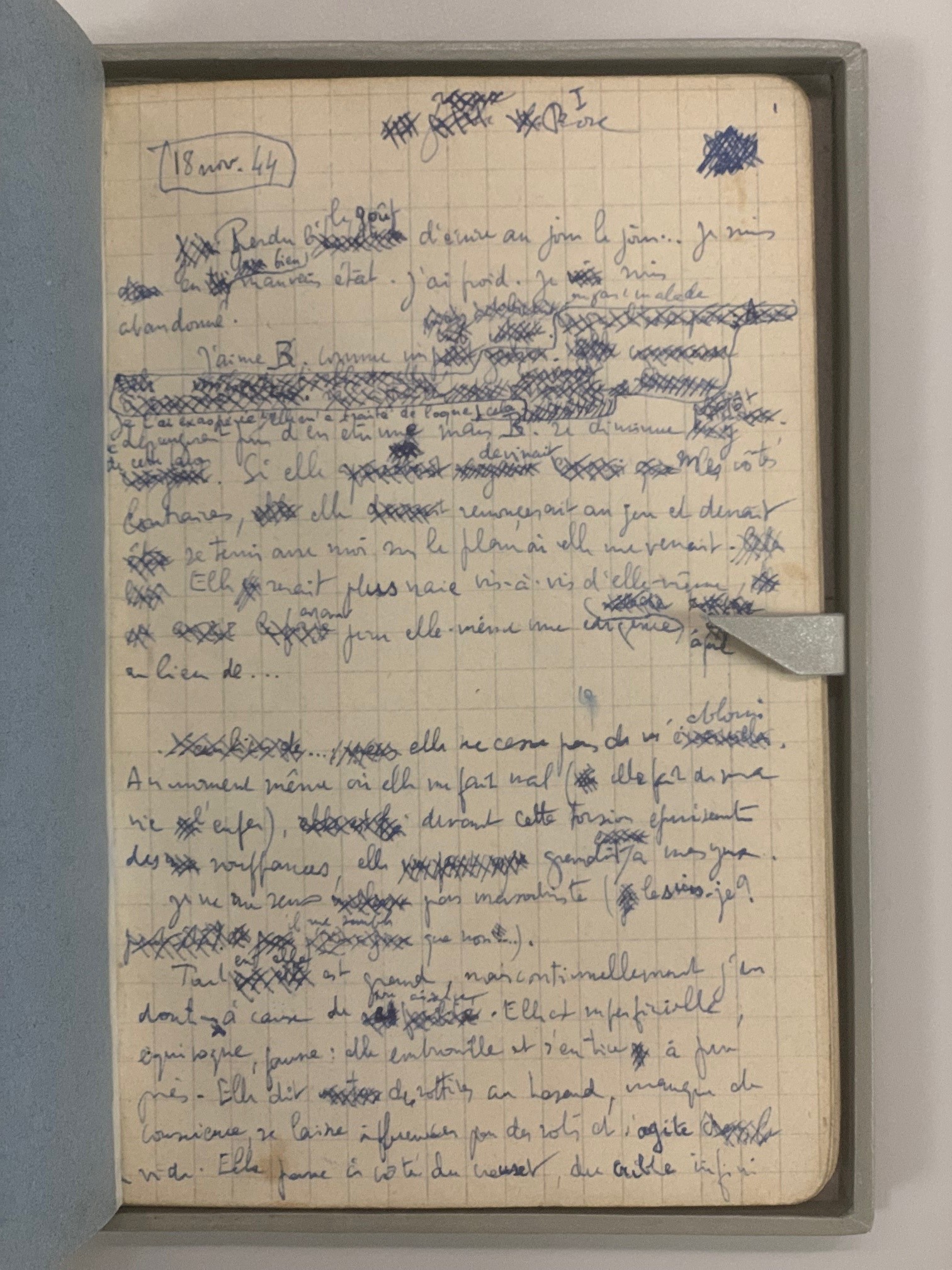

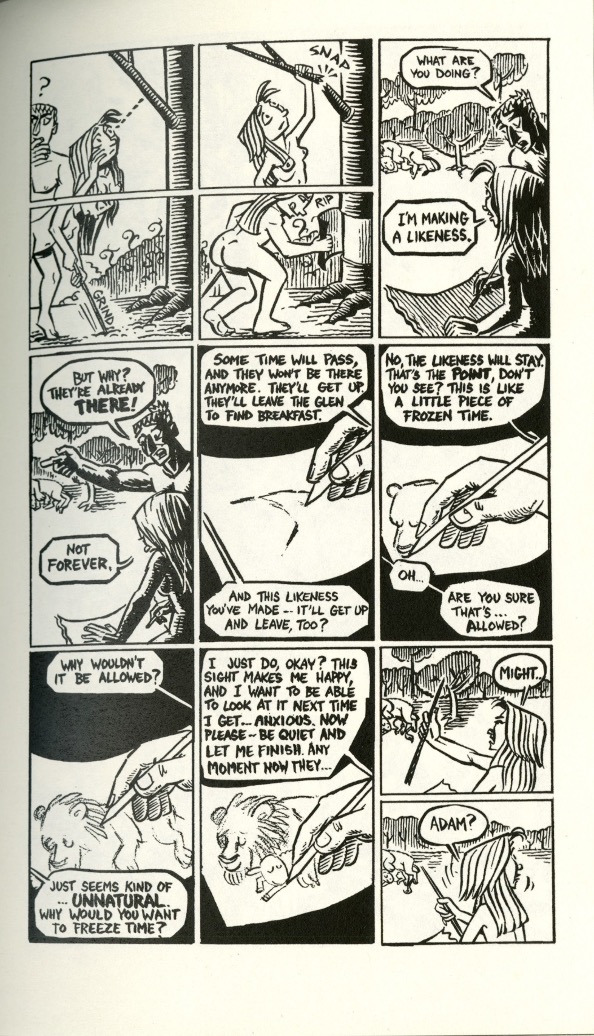

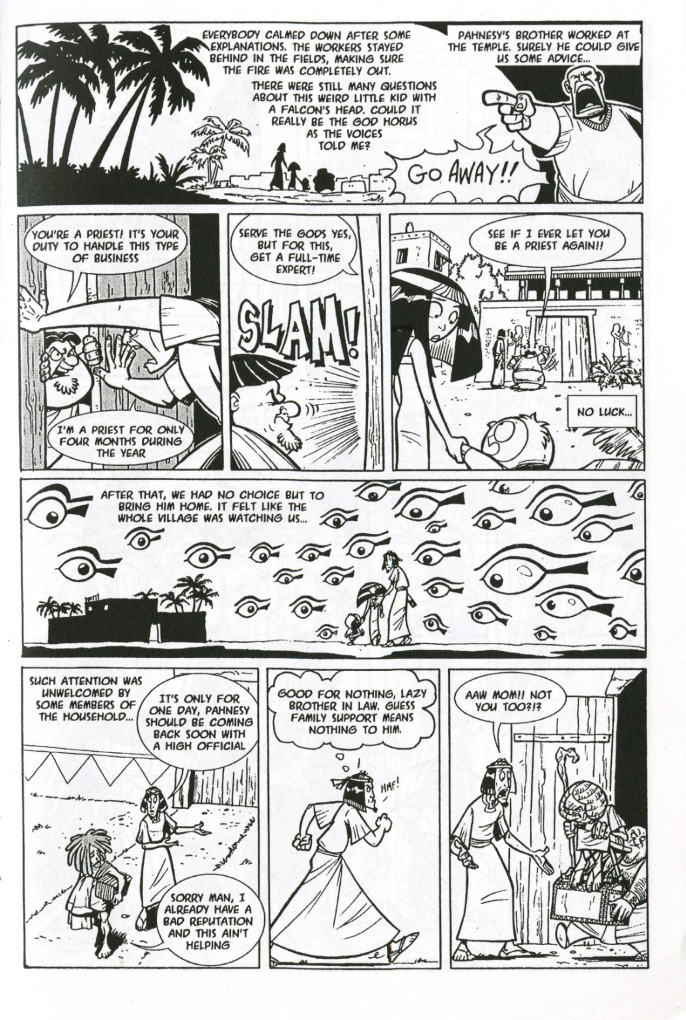

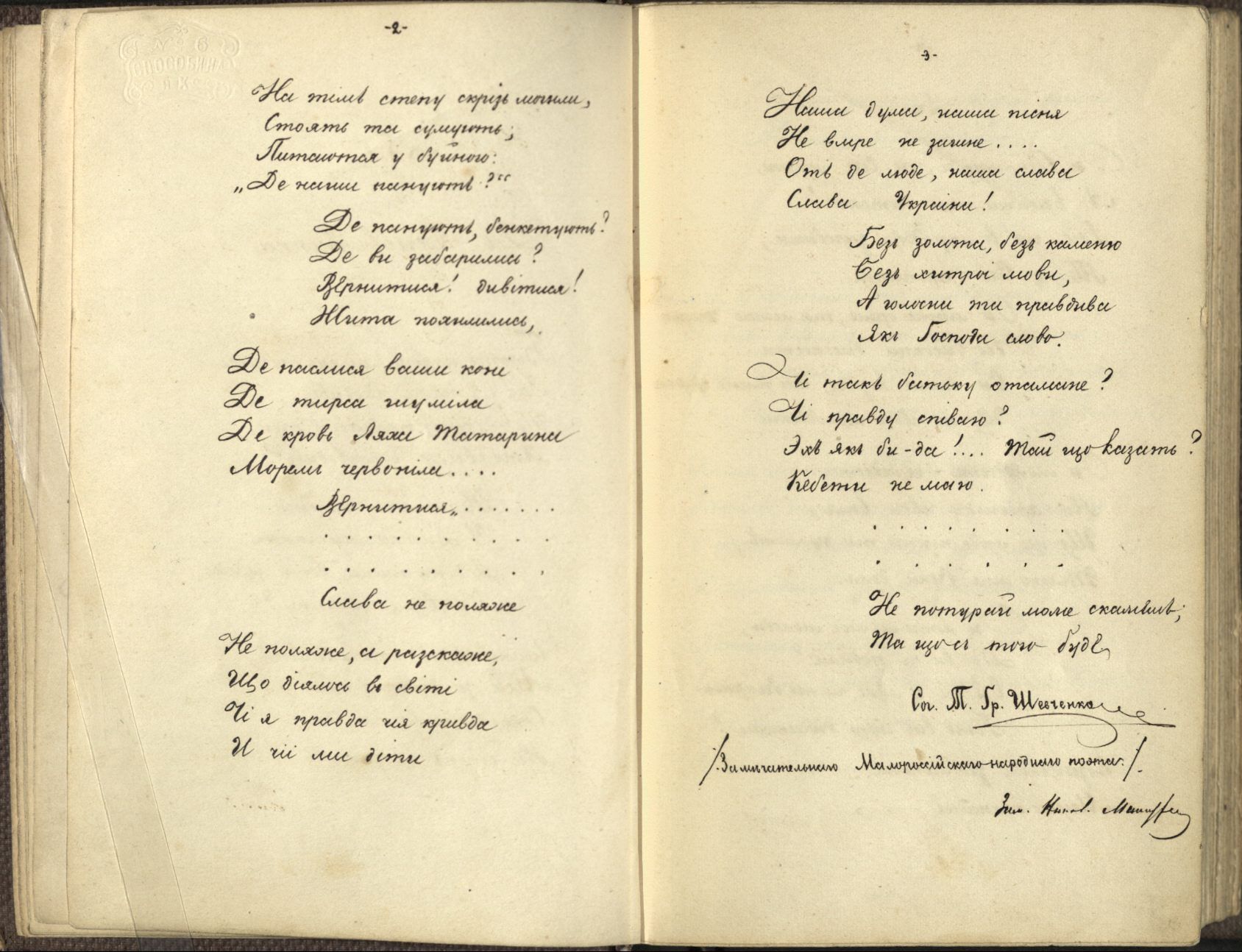

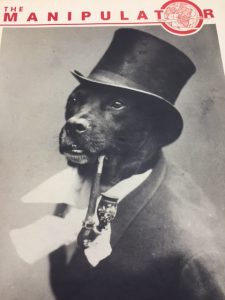

Monday, Part 1, pages 5-6

Monday, Part 1, pages 5-6

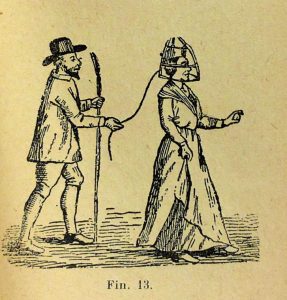

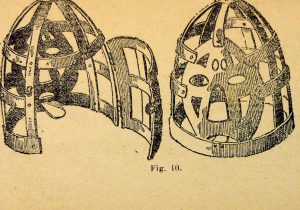

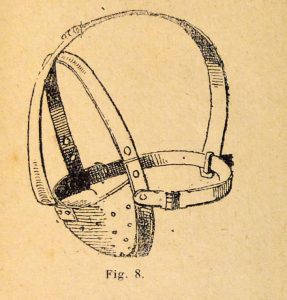

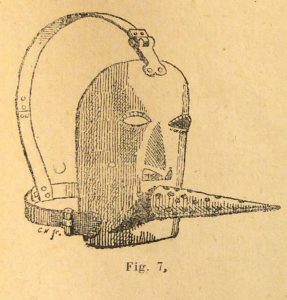

The part inside the mouth would sometimes be spiked or have a sharp edge so that if the woman moved her mouth at all she could injure her tongue or mouth. Then the offending “scold” could be led around town in this contraption to further humiliate them and have them repent their mouthy ways. I was amazed at the range and variety of the muzzles that were represented in this volume.

The part inside the mouth would sometimes be spiked or have a sharp edge so that if the woman moved her mouth at all she could injure her tongue or mouth. Then the offending “scold” could be led around town in this contraption to further humiliate them and have them repent their mouthy ways. I was amazed at the range and variety of the muzzles that were represented in this volume.

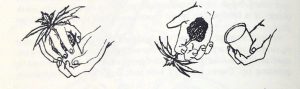

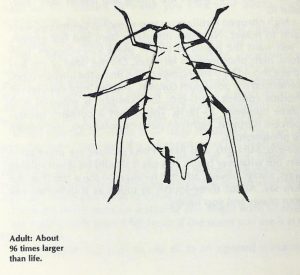

Typically they attack the tender growth tips and buds and can injure plants by sucking the juices from both the stems and leaves of the plant as well as excreting honeydew which serves as a culture for black mold. Unchecked they will spread over the entire plant then move onto others. Aphids are only about one thirty-second of an inch long and are prodigious at producing offspring. Faber counsels that there are really only two choices, one involves going organic and using their natural enemies either the ladybug or the praying mantis and the second involves spraying with insecticide.

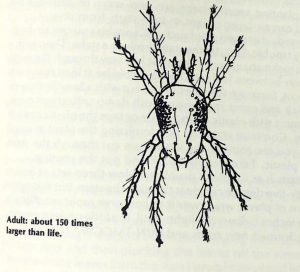

Typically they attack the tender growth tips and buds and can injure plants by sucking the juices from both the stems and leaves of the plant as well as excreting honeydew which serves as a culture for black mold. Unchecked they will spread over the entire plant then move onto others. Aphids are only about one thirty-second of an inch long and are prodigious at producing offspring. Faber counsels that there are really only two choices, one involves going organic and using their natural enemies either the ladybug or the praying mantis and the second involves spraying with insecticide. They can vary in color and are so tiny it takes a magnifying glass to see them clearly. Often you can only spot them by looking at the underside of the leaves where small dots of silver indicate the webs to which eggs are attached. They multiply quickly and your only option is spraying with insecticide again and again.

They can vary in color and are so tiny it takes a magnifying glass to see them clearly. Often you can only spot them by looking at the underside of the leaves where small dots of silver indicate the webs to which eggs are attached. They multiply quickly and your only option is spraying with insecticide again and again.