Evgeny Morozov over at Foreign Policy has an intriguing post that asks a couple simple but still difficult to answer questions: Who are bloggers, and how does this impact how we defend them when they are arrested for what they write? Evgeny was reacting to a recent Committee to Project Journalists report on the ten worst places to be a blogger, which my colleagues over at the OpenNet Initiative blogged about last week.

The crux of the matter for Evgeny boils down to identity and how various interests label bloggers. This is an issue that has actually come up in a number of conversations I’ve had recently with bloggers and activists from the Middle East, and it is clear to me from those conversations that they have multiple identities. Some folks I know here at Berkman probably think of themselves primarily, or substantially, as bloggers (I’m thinking of Ethan Zuckerman, Doc Searls and David Wienberger, among others). But many others that I have met, who write widely read blogs, actually have identities that they put well ahead of ‘blogger’: usually journalist, activist, writer or professor, to name just a few.

In the US, this might partly be explained by the fact that blogging is still often looked down upon by many traditional journalists who see it as an affront to their profession, and for the blame many assign to the Internet for its role in the demise of the newspaper industry more generally. While this view is slowly changing, I still often see a tone of condescension in how many traditional journalists discuss blogs and ‘what those blogs are saying,’ even though journalist use them as an important part of their daily work. In the US, though, online speech is still largely, if not yet completely clearly, protected, and can be defended when frivolous lawsuits are used to try to limit otherwise protected speech.

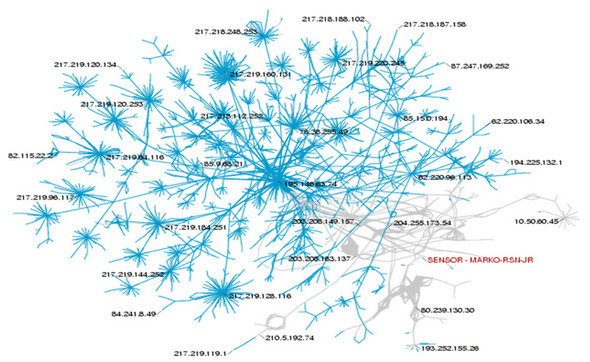

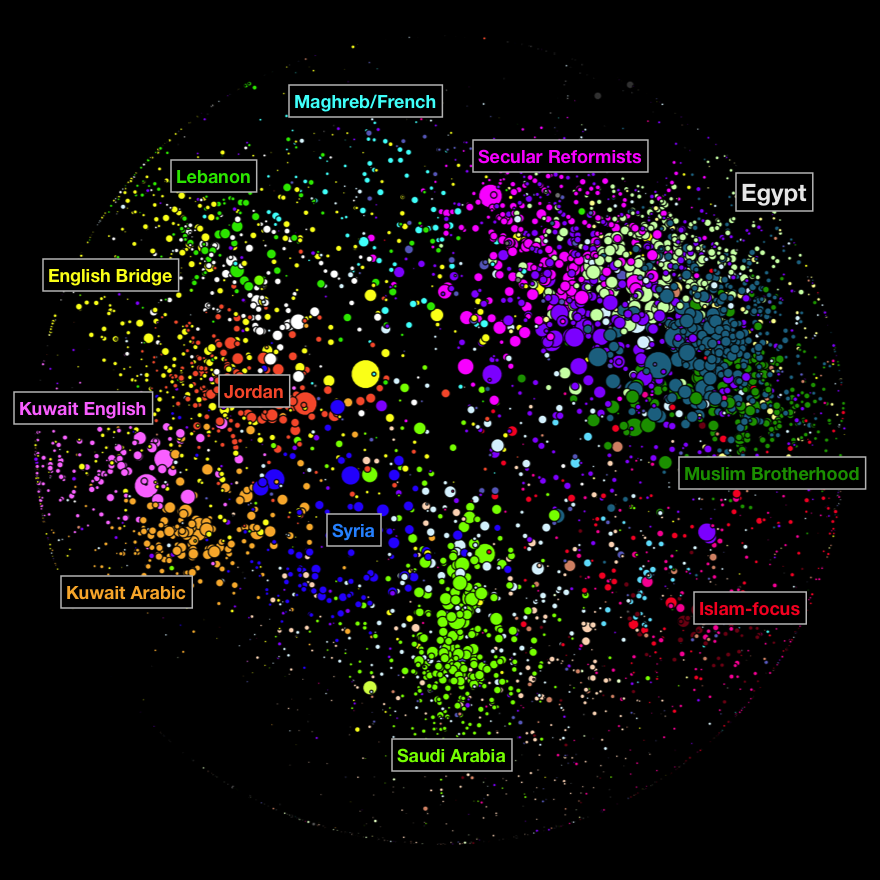

This is not the case for many of the individuals who are arrested overseas for what they write on blogs, though. The ability to write online anonymously can in many ways protect bloggers, but, as our studies into the Iranian and Arabic language blogospheres have shown, bloggers tend to write with their name more often than not, especially political bloggers. Their other identities, as activists, writers, journalists or politicians, may actually offer a higher level of protection, informal or formal, than the moniker ‘blogger’ ever might.

The practical question of how to protect those that are arrested for their blogging seems, in my mind, to come down to this: online speech should be protected, and people writing honestly about their personal opinions should have a protected right to do so, except in extreme circumstances. There are actually few laws abroad that currently limit online speech (I’m thinking of Iran, for example); instead, at least in many countries with limited freedom of expression, bloggers are prosecuted for threats to national security, insulting the nation or its leaders, or violation of other equally ill-defined concepts. So, yes, bloggers have multiple identities of their own choosing, and we may in some cases inaccurately label them primarily as bloggers. But that shouldn’t really matter. When it comes to the arrest and prosecution of individuals for what they write online, their right to freely express their opinion on any platform they choose should be respected and defended. Full stop.

Click Here

Click Here