Google Releases Transparency Report, Showcases Government Censorship Worldwide

September 23rd, 2010 — Marianna TishchenkoOn Tuesday, Google released a Transparency Report that shows the number of government inquiries it receives for information about users and requests for Google to take down or censor content.

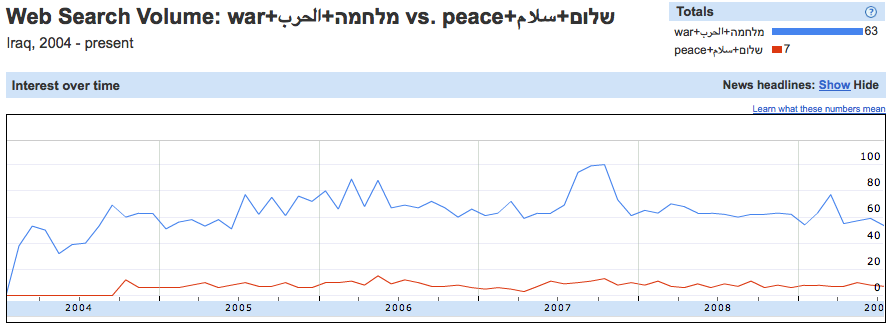

The report, which Google presents in the form of an interactive map and traffic graphs, reveals the number of content removal and data requests that it received from government agencies around the world during the first 6 months of 2010. (See this Herdict post on the traffic graphs.)

The map tool allows one to see:

- The number of government requests we received to remove content, per country;

- The number of individual items asked to be removed, per country (as there may be many URLs per request) — this is new for 2010 data;

- The products that contained the content; and

- The percentage of those requests that we fully or partially complied with on a country-by-country basis.

Internet censorship around the world is on the rise, according to the report. A comparison of data from the internet service database that it released 5 months ago and the current version shows that there has been an increase in the number of government requests, suggesting that internet freedom may be taking a turn for the worst. Note: the map tool excludes data request information for a number of countries, most notably China and Iran. Using the traffic graphs, however, one can see how much traffic Google services get in those countries. The U.S. currently occupies the #1 spot with 4,287 government requests for data information during the first half of 2010. Directly behind it are Brazil with 2,435 and the U.K. with 1,343. Just five months ago, however, Brazil was in first place, the U.S. in second, and the U.K. in third.

While the report does contain important and telling information about censorship levels worldwide, the data that Google provides is not totally comprehensive and accurate. It fails to address a couple of major criticisms that arose when it first released an internet service database. Most notably, the tool does not reveal query specifics, such as how many requests government agencies made for the same user data and what the total amount of requests across all categories of content is. Google also admits that among its limitations is the fact that that it has not included statistics for countries in which fewer than 30 requests for user data in criminal cases during the observation period.

Moreover, the report does not account for government-mandated service blockages—only content removal requests. A major addition that Google has made to the tool, however, is the ability to see how many requests it has honored: 138 in the US, 398 in Brazil, and 48 in the UK.

Google says that it would like to be able to share more information with the public, but lack of standardization among user data requests, as well as the difficulty in categorizing and quantifying those requests, prevent it from doing so. But the internet search giant has expressed its intention to offer more information in the future, as well as a desire to fuel debate on government censorship.

“We hope this step toward greater transparency will help in ongoing discussions about the appropriate scope and authority of government requests,” Corporate Development and Chief Legal Officer David Drummond said in a post on Google’s official blog.

Click Here

Click Here