Making Khoubz al-Riqaq

May 5th, 2012

I made Koubz-al Riqaq partly because I was sad that none of our readings addressed the culinary arts in the context of Islamic devotion. This dish is a thin Arabian pan bread. It is made without yeast and fried in a pan. It is normally served for the suhur meal of Ramadan, eaten just before sunrise. I found this recipe as part of an online Sufi cookbook; we spend a lot of time focusing on music, dance, and prayer in the Sufi tradition, but not food. The recipe is very simple; the ingredients are minimum, which I thought coincided with asceticism and a sense of self-discipline. Of course, this is also a dish that one would eat before beginning the fast each day, so it also makes sense that it would be somewhat spare.

While making the bread I thought about what linked to the Sufi traditions that we had learned about. One thing that came to mind particularly was the kneading of the bread, which is repetitive and somewhat meditative. The reason that I chose to focus on making food for one project is because food certainly functions to bring people together. Ramadan is interesting in that it is both the act of fasting as well as the act of breaking the fast that brings people together.

For this piece I filmed the act of making the food and said a prayer from the Mevlevi order for the food.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=urEPOHbNqcs

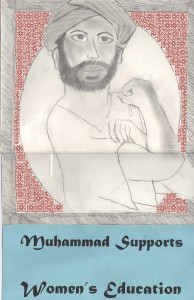

Looking at the art work from the Islamic Revolution inspired me to make propaganda posters of my own, however with an emphasis on feminism. We learned that Iran, a majority Shiite nation, often had posters praising the family of Muhammad. The narratives of sacrifice and standing up for the right thing in the face of sure defeat when the succession of Muhammad was contested, is a story told over again. Those same figures figure into the iconography of Iranians, particularly during the Islamic Revolution and the Iraq war.

We often perceive the propaganda to be negative word, in certainly has many negative associations in world history. However, I think art can be used for political purposes. Images, symbols, etc are extremely powerful and such representation can galvanize populations to act for good things and bad. Certainly the posters concerning the Islamic Revolution disseminated an image of the Shah as a tyrant and depicted an Iran that was ready and ripe for more democracy while yearning for a sense of nationalism. Whether the Iranian Revolution turned out exactly as everyone planned, the posters represent a moment of idealism.

I thought about what posters I would have had I been an activist in Iran at the time of the Revolution and what poster I would make in the U.S. today. I combined an image of Rosie the Riveter, an iconic figure of female strength and independence, with a figure that is supposed to be Muhammad. Representationally, the image suggests a mere blending of western feminism with Islamic faith. Additionally, in the framing of Muhammad, I included something that might by describe as Arabesque. The images I chose are somewhat essentializing, but I purposefully chose images that were cliché because they are often times most legible for the widest audience. And of course, one of the aims of propaganda is to reach the widest audience. Arguably, I imagine the poster would be most legible in a nation like the U.S.

The message at the bottom of one poster says, “Muhammad supports Women’s Education” and the second says, “Muhammad opposes the war against women.” The first is meant to address one of the concerns people had in the Islamic Revolution. Though Islamicization may have resulted in a shift in societal codes that are considered stricter for women, it also allowed women greater access to education. The second poster address one of the ongoing political issues in the United States, attacks on birth control have been framed as “A War on Women.” I think this is interesting because that phrasing also is charged with other campaigns from the Right, such as the “War on Terrorism” or the “War on Drugs. I can imagine similar posters saying “Muhammad opposes the War on Terrorism” or “Muhammad opposes the War on Drugs.” I see the importance of propaganda, also in the case of the posters I made, to be that it can create positive associations and create new signification that are productive to the project at hand. Thus my posters attempt to tie Islam to feminism by reappropriating symbols that we see in similar but unfamiliar contexts.

My first rap single

May 3rd, 2012

I wrote this rap after thinking about the influence of the Islamic tradition in hip-hop. I listen to hip-hop religiously and it means so much on multiple levels, intellectually and artistically, because the artists of the 90s were so adept at their craft. Also, emotionally, because hip-hop represents the black experience in the U.S. in a way that desires to speak truth, but in a way that is reaffirming and applauding of the black identity.

It was really interesting to think about the role Islam had in that self-affirmation. So early on in the song I compare my experience of finding hip-hop to black America’s experience of finding Islam. Later, I make a critique of Christianity within the America’s with a line that says, “doctor, doctor, they telling me I’m Goody Proctor/ they wanna give me some lick cuz they say I’m a witch/ that’s way I had to let go and make a switch.” The reference to the Salem witch trials is fruitful because it contacts fear of black religion and spirituality within the U.S. Christian framework. And then, of course, the switch, refers to the moment of conversion to Islam. What those lines mean to invoke is the pain in accepting a belief system that condemns you or a belief system forced upon you. In the American context, African Americans have embraced Islam partly for those reasons.

In the first line of the first stanza, I mention Michael Knight. His book brought up many interesting questions for me, for which I don’t necessarily have the answer. So I ask “why a white knight always gotta be a pioneer.” This conflates the ideals of the Crusades with the ideals of American frontierism, while making a gendered and racial comment on who often can make new discoveries, whether physical or cultural, or whose discoveries receive recognition.

In this verse I also refer illness, kind of in a similar vain to those poems that we read earlier in the semester in praise of the prophet. And so, even as much of the song questions what is it to have faith, what it is to be religious, the underlying impulse within it is to turn to a higher spiritual realm. I think this is also what Michael Knight is doing in his book, and so I also wanted to show that worship can be complicated, but by locating in the history of a black experience in the U.S.

Lyrics

They say that Hip Hop came from the souls of black folk

from the toll of this historical joke

they let us soak

in self-perceptions black face of our lack

sometimes it’s the mind holdin you back

without a doubt, the music came to save me, sounding like clikety clack

I began to like the fact that I was black

like the moment black America found Muhammad

why do we need something to applaud

outside of ourselves, apart

from ourselves what is it that we wanna feed the heart

we know we’ll never turn to the start

words are choked, origin ain’t nothin more than a myth

so we learn to speak in new tongues till we find the right pitch

Michael Knight in search of Islamic America, edge of the frontier

egos wanna say eureka, why a white knight always gotta be a pioneer

to criss cross, toss, at any loss to conquer new lands

but what if glory ain’t nothin but the desert sand

then we’re lookin for the sign that’s magic

till it comes, belly still achin quaking core still sick

that’s when God comes in

turnin everythin to stain glass

hopin the pain’s gonna pass

doctor, doctor, they tellin me i’m goody proctor

they wanna give me some licks cuz they say I’m a witch

that’s why I had to let go and make the switch

embrace an ideology that don’t negate

we too afraid to say we tired of self- hate

i gotta love everythin from the soul of black folk

My people’s been speakin to me through the rap

there’s gotta be some essence that I can tap

before the beat slows to a stop

and I close my eyes for a never ending nap

nearer to the source, losin my remorse

we gotta redraw the map

those borders look artificial

cuz of you, I think I’m partial

to love

a Sufi once told me there was no difference tween me and you

though I know we gotta struggle

tired of this politickin

though this time bomb be tickin

even as I try to keep this rhyme

someone’s tryin smuggle trouble tween our words

gotta have patience though it seems we losin sense

too many people ain’t got two pence

language slurred

like blibber blabber

at our own pace

hopefully we regain the swagger of god’s grace

Foundations

April 25th, 2012

I made this sculpture in response to Michael Sell’s “Erasing Culture: Wahhabism, Buddhism, Balkan Mosques.” I constructed five pillars out of a variety of materials. The five pillars, of course, refer to the ritual practices that are said to be the foundation of Islam, the shahadh, fasting during the month of Ramadan, prayer five times a day, the zakat, and the hajj to Mecca. Sell’s article and the presentation we watched in class about the destruction of Balkan Mosques got me thinking about the other foundations of faith and culture. The article highlights the importance of physical space, and so that is why I depict five physical pillars in my sculpture. As much as The Five Pillars of Islam are significant to the practice of faith, so is the need to have a space that conveys particular meanings, histories, and cultures such that the people who use that space feel as if it is there own.

The first pillar is made out of wooden brick and stone the blocks, the last pillar out of leafy material, in order to convey the place nature and the natural world has in worship. The three middle pillars are created out of various synthetic papers and fabrics in order to emphasize the human role and input not only in the creation of worship space and the sort of representation they entail, but also because these divine creations can be integral to an individual’s sense of self and how people imagine their relationships within the society. That the pillars are all made out of different materials is meant to impress upon the viewer the diversity of expression in Islam.

There is a book resting on the pillars. Its spine in one picture says faith and its spine in the other one says culture. This is to suggest that faith and culture entail knowledge, but that knowledge depends on certain structural realities that make possible spaces for the spreading of the knowledge.

Quran/Recite

March 17th, 2012

The following is a depiction of the word ‘quran’, drawn close to the ear of a person. Quran literally means ‘recite.’ The word written here, in Arabic script, does not mean al-Quran, as in the noun form of the word referring to the holy book. Rather, it takes on the verb form of the word.

The depiction attempts to capture the moment in which Muhammad, on Mount Hira, was told to recite. That was the beginning of the Quran. The readings on recitation emphasized the oral tradition and practice tied to Islam and the Quranic text. The hafiz is the person who is the guardian of Quran, or in other words the person who memorizes and recites the Quran. Even before Arabic had a script, the Quran was transmitted first from Allah to Muhammad, then from Muhammad to his followers, and so on.

I think of this image as tied to the continued tradition of recitation all over the Islamic world. I imagine the impulse or motivation to practice recitation an infinite loop. One hears recitation and is inspired to take it up. When one recites the Quran for others, they too might be inspired to recite. But always, the primal moment of communication, before one can even speak the Quran, one must first hear it.

I thought about representing the word as if it were coming from a mouth, in order to highlight its aural quality as opposed to its written quality. The drawing might suggest that the writing precedes the hearing and then speaking—which is not depicted here. Of course, the written and calligraphic representation of the Quran came last. However, if the word is simply present in the drawing—without a representation of the body of the speaker—then it is possible that the word is spoken by Allah. From many discussions about art and representation in Islamic art, we learned that Allah cannot be represented in any form, known or unknown. In representing the word with no physical speaker I mean to invoke that first moment of listening and then recitation.

Charcoal on paper

Muhammad heard “recite,” and he did,

till his words grew like roots into our souls

I.

The Prophet like a bird takes flight

Returning to the bosom of Allah

The Light of Muhammad persists here

Even as his body falls to the material world

Praise Allah, he sent Muhammad with the Book

So to guide his people from darkness

From sickness into health

From solitude into love

Muhammad heard “recite,” and he did,

till his words grew like roots into our souls

II.

Arabia fell silent that days

His followers’ heads hung low

The ache of melancholy like hunger

In their stomach

Not an eye was dry

But rejoice, we know Allah

Because Muhammad came to us with his words

Muhammad heard “recite,” and he did,

till his words grew like roots into our souls

III.

The day Muhammad went, Allah wept

Even the Beloved knew of earthly suffering

Though he had a mantle about his shoulders

Oh! The immortal light of the Prophet!

The mortal man that is Muhammad

Lives on by our humble imitation

Muhammad heard “recite,” and he did,

till his words grew like roots into our souls

Poems after the Prophet’s death

March 12th, 2012

These poems are in response to the poems in praise of Muhammad. I wrote these poems in the style of the mauluds, poems written in veneration of the Prophet’s birth. Maulud actually means “newborn child.” The Sindhi maulud is a short lyrical poem from five to ten lines. The Sindhi maulud begins with a thal, or a verse that generally serves as a refrain.

While the style of these poems is modeled structurally after the maulud, they are different in content. Rather than writing on the birth of Muhammad, I chose to write on his death. The poems based on the Prophet’s birth entail an immense sense of hope, love, of course, and happiness. There is a sense of seeing the world anew. Take this line for example, “Beauteous guidance came into existence when the prince Prophet was born.” In invoking the Prophet’s birth in these poems, he already is the “example” and he already is the one who will guide those who follow him to Allah.

Given that there was so much confusion after Muhammad’s death concerning who would succeed him and, as a result, lead the Muslim community, I wanted to write poems that would hold onto that same sense of hope and guidance that we see in the maulud. For me, these poems imagine a time soon after Muhammad’s death, just preceding the political chaos that would ensue. The poems imagine a time of profound mourning for that loss while expressing extreme gratitude that he came with a message that would last, even though his body did not.

The sense of mourning is the greatest difference between the mauluds and the poems I’ve written. The mauluds are full of happiness, in fact, many of them suggest a sense of having one’s grief subside because of Muhammad’s birth. My poems can be characterized by a shared mourning that must be suffered. We can imagine that all those who admired and followed the Prophet would have uniformly felt this deep sadness at the news of his death. In so doing, the poems signal a hope and need that the community will remain in tact because of the love everyone shared for the prophet.