It has been over a month since Thailand’s military junta, the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), overtook the country’s government during a May 22 coup. Since then, the NCPO has aimed to consolidate political control of the country, an impulse that has filtered down to controlling nearly every minute facet of citizens’ public and private life. Citizens in Thailand can’t gesture with Hunger Games-like salutes, nor can they read such texts as Orwell’s 1984 and Filipino revolutionary Jose Rizel’s Noli Me Tangere in public spaces. Those acts, the junta claims, are expressions of radicalism.

2014 Thai Coup, via Wikimedia Commons.

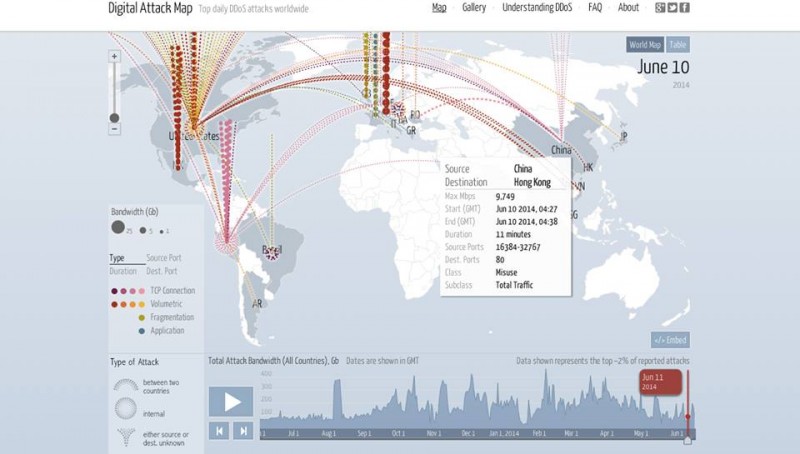

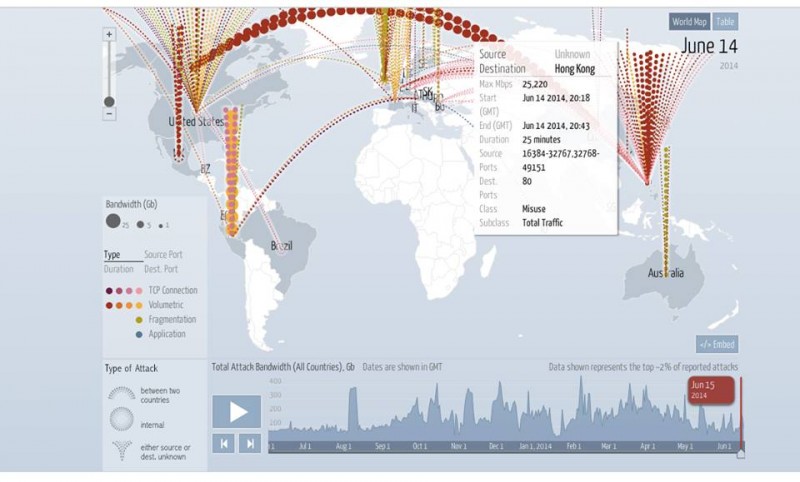

The NCPO has increasingly moved this strategic policing online. They have ordered Thai ISPs to shut down over 200 sites. Some casualties of this call for censorship include Prachatai, an independent online newspaper; the Asia and Thailand subpages of the Human Rights Watch, which published an incriminating report detailing the country’s 2010 Red Shirt protests; and Facebook, which was blocked for a day on May 28 before the NCPO swiftly unblocked it, citing a “glitch” that activists have chalked up to a social media “kill switch.” When the government tried to set up a meeting with Facebook and Twitter to discuss tactics for censoring anti-junta impulses on social media, the companies in question didn’t show.

Police forces have warned citizens against “liking” any anti-government posts on social media. Last week, news emerged of a Facebook phishing ploy orchestrated by the government – one in which Thai netizens were tricked into giving their personal information, contained in their Facebook accounts, by being asked to “log in via Facebook.”

Access Now recently reported that the junta is now organizing governmental panels that will surveil all facets of national media, extending to online media platforms. The junta is offering monetary incentive to those citizens who turn in photos, videos, or other incriminating evidence of people criticizing the junta.

Lisa Gardner of PBS MediaShift attributes this censorship to the junta’s desire to foster a sense of allegiance towards its regime. For many citizens, the Internet is largely losing its function as a forum through which netizens can access information, share opinions, and fight against the climate of fear engendered by the junta, whom Gardner claims is trying, in earnest, to convince Thailand’s citizenry of its good intentions.

2010 Red Shirt Protests, via Wikimedia Commons.

Writing in Global Voices Bridge, an anonymous Thai journalist described firsthand the current situation as one in which citizens can “feel total censorship in the air.” The journalist notes that Thailand’s history of military takeovers, such as 2010’s aforementioned Red Shirt protests, saw a similar shutdown of media outlets. This created a political climate in which lack of informational access, coupled with an online media milieu that is curated excessively by Thailand’s junta, led to citizen compliance with human rights atrocities – a risk the anonymous journalist feels may be presented by the NCPO’s current hold over online communication outlets.