credit: zeevveez/Flickr

On June 14, 2013, Google announced that it would begin sending experimental balloons, loaded down with Internet hotspot equipment, into the stratosphere to help connect the estimated 4.5 billion people who do not have access to the Internet, many of whom live in rural areas. Google’s project, named “Loon,” quickly grabbed the attention and imagination of people living in countries where Internet censorship is the norm. Abdullah Hamed, CEO and founder of the popular Saudi gaming platform GameTako, reacted to Google’s announcement by posing a provoking question (or taunt) to local Emirati telecom companies and the Saudi government on Twitter.

Hamed’s question was a good one to put to the Saudi government and telecom companies who regularly block websites and ban unsanctioned communications services such as the VoIP product Viber. Hamed’s question soon got an answer, but not from the Saudi government or any other state that censors its Internet; Hamed was answered by Google. The company announced that it would be obtaining all the proper air travel permissions and radio frequency licenses, and will connect with local telecom networks as its balloons float by.

credit: purolipan/Flickr

In the late 1970s, small numbers of Iranians were permitted into Iraq to worship at the shrine of Imam Ali. After most of the pilgrims left the shrine, the exiled Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini would give impassioned anti-Shah lectures to the remaining visitors. Khomeini’s speeches were recorded onto cassette tapes, copied, and widely distributed on the streets of Tehran and other Iranian cities. The Shah’s government was aware of the tapes, and often destroyed copies it could find, but it did not manage to sufficiently disrupt the distribution network, and Khomeini’s influence in Iran grew. The CIA and the Shah’s information intelligence communities, looking in the wrong places, failed to see that the ground beneath them had shifted and were caught by surprise when the Iranian Revolution ousted the Shah’s government. In today’s increasingly connected world, we would call Khomeini’s followers members of a “sneakernet.” A sneakernet refers to the transfer of electronic information like computer files using removable media like magnetic tape, floppy disks, CDs, DVDs, USB flash drives, and external hard drives by someone wearing sneakers. While sneakernets do still exist, many hung up their sneakers once broadband made sharing files faster and easier.

credit: Tony Marr/Flickr

Hamed’s excited tweet expressed his hope that floating balloons would connect people to the Internet and thwart government censorship policies. Instead of investing his hopes in Google Loon, Hamed might take seriously a proposal from the early days of the Internet that seems loonier than Google Loon, but might be more practical for circumventing network censorship or avoiding government scrutiny by programs like PRISM or the recently discovered snooping via the US Postal Service: IP over Avian Carriers (IPoAC). On April Fool’s Day, 1990, David Waitzman submitted a Request for Comments (RFC) to the Internet Engineering Task Force, the ad hoc body charged with developing and promoting Internet standards, on the idea of using carrier pigeons or other birds for the transmission of electronic data. Nine years later, again on April 1st, Waitzman issued another RFC suggesting improvements to his original protocol. On April 1, 2011, Brian Carpenter and Robert Hinden made their own RFC detailing how to use IPoAC with the latest revisions to the Internet Protocol IPv6. While Waitzman, Carpenter, and Hinden clearly designed IPoAC as a joke, using birds to transfer digital media has been successfully tested. In 2004, inspired by the IPoAC idea, the Bergen Linux group sent nine pigeons, each carrying a single ping, three miles. (They only received four “responses,” meaning only four of the birds made it.)

credit: Alan Mays/Flickr

Not all the tests have ended in failure. In 2009, a South African marketing company targeted South Africa’s largest Internet Service provider, Telkom, for its slow ADSL speeds by racing a pigeon carrying a 4 GB memory stick against the upload of the same amount of data using Telkom’s service. After six minutes and 57 seconds, the pigeon arrived, easily beating Telkcom, which had only transferred 4 percent of the data in the same amount of time. In 2010, another person hoping to shame their ISP in Yorkshire, England raced a five-minute video on a memory card to a BBC correspondent 75 miles away using a carrier pigeon while simultaneously attempting to upload the same clip to YouTube. The pigeon made it in 90 minutes, well ahead of the YouTube video—which failed once during the race. In Fort Collins, Colorado, rafting photographers routinely use pigeons to carry memory sticks from their cameras to tour operators over 30 miles away, and prisoners in Brazil have been caught using pigeons to smuggle cellphones into their prison cells.

credit: Windell H. Oskay/Flickr

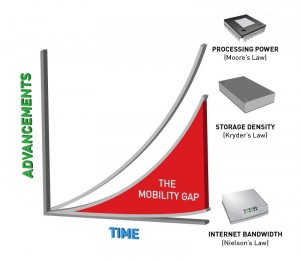

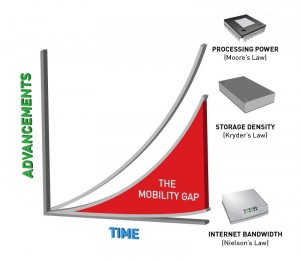

Suggesting that pigeons might be faster than Internet connections might seem ridiculous, but as the information density of storage media has increased, and continues to increase, many times faster than the Internet bandwidth available to move it, IPoAC might not be so far-fetched. Over the last 20 years, the available storage space of hard disks of the same physical size has increased roughly 100 percent per year, while the capacity of Internet connections has only increase by 30-40 percent each year. Sneakernets might have gone out of fashion as bandwidth speeds increased, but as storage capacity increases—along with our need to fill those capacities—pigeon-powered networks may become a practical alternative to existing networks. While no one brought up the idea of using pigeons at Google’s “How green is the Internet?” summit last month, pigeons may also be a more sustainable and environmentally friendly way to transfer data in the future.

Even if the increasing gap between storage and mobility doesn’t become a problem, Internet censorship or privacy issues might spur the development of a Pigeonet. Earlier this month Anthony Judge, who worked from the 1960s until 2007 for the UN’s Union of International Associations and is known for developing the most extensive databases on global civil society, published a detailed proposal titled “Circumventing Invasive Internet Surveillance with Carrier Pigeons.” In the proposal, Judge discusses the proven competence of carrier pigeons for delivering messages, their non-military and military messaging capacity, and the history of using pigeons to transfer digital data. Judge acknowledges that pigeon networks have their own susceptibilities (such as disease or being lured off course by an attractive decoy), but argues we should not be so quick to dismiss the idea. As governments, and compliant corporations, increasingly block or filter access to the Internet, data capacities and data production increase beyond bandwidth limitations, and we begin to realize the environmental costs of running the Internet, sneakernets and pigeonets may become increasingly attractive options for transmitting data.