A new report from the Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto takes a look at Internet monitoring in Iraq. Since violence led by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) broke out in the country several weeks ago, the government has responded by cutting Internet access, first by blocking websites including Twitter and Facebook and then, on June 15, issuing orders for a total Internet shutdown in five of the nation’s 19 provinces.

Among the report’s key findings:

- A total of 20 unique URLs were found to be blocked on three major Internet service providers (ISPs): Earthlink Telecommunications, IQ Net, and Newroz Telecom. The blocked sites include Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Skype, YouTube, WhatsApp, and WeChat, as well as popular VPN services including OpenVPN and StrongVPN.

- The majority of the websites found to be unavailable corresponded with the list of that the Ministry of Communications ordered to be blocked on June 13. The ISP Newroz Telecom showed no signs of filtering, which “was expected, because this ISP serves the Kurdistan area, and reports have indicated that the shutdown and social media blocking orders did not include Kurdistan.”

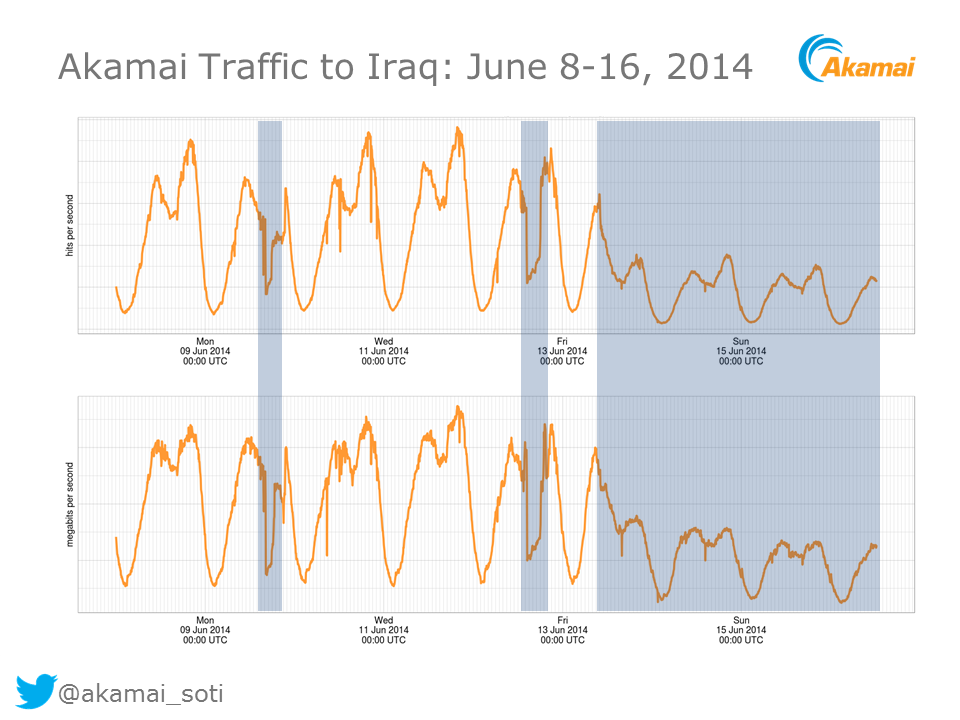

Traffic from Akamai, a content delivery network, to Iraq, showing a sharp drop in traffic since the filtering orders from the Iraqi Ministry of Communications. Via the Citizen Lab.

- The Citizen Lab also looked at seven websites “affiliated with or supportive of” ISIS. None were blocked. “Given that the insurgency was cited as the rationale for the shutdown and filtering,” wrote the authors, “this finding is curious.” This could suggest that the Maliki government is using the present crisis as an excuse to rein in broader social media around the country—whether or not it is related to ISIS violence.

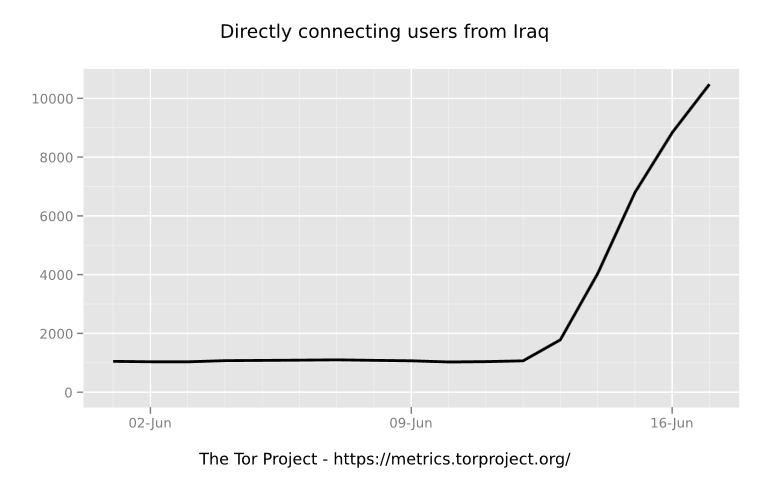

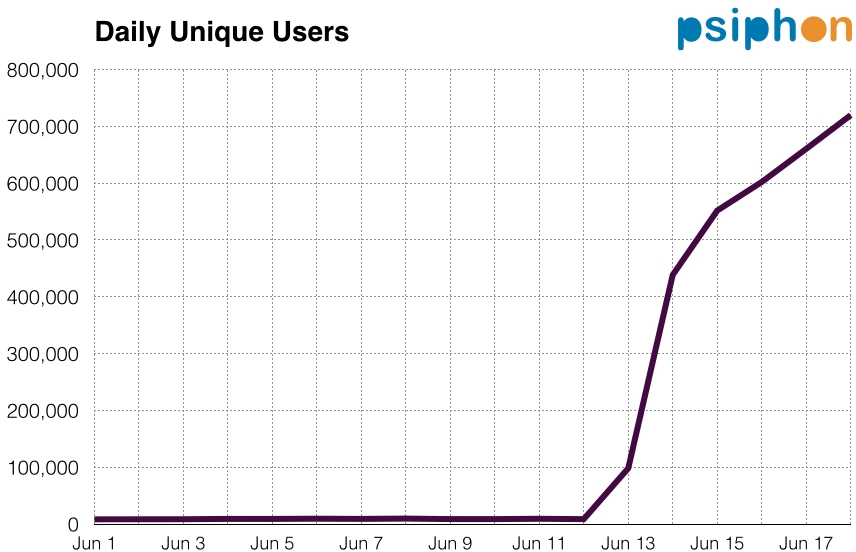

- Usage of Psiphon and Tor, which allow users to circumvent filtering, has soared in Iraq in recent days (though Tor use has since fallen slightly).

Directly connecting users of Tor in Iraq, via the Citizen Lab.

Daily users of Psiphon in Iraq, via the Citizen Lab.

More information about the Citizen Lab’s analysis can be found in its report, Monitoring Information Controls in Iraq in Reaction to ISIS Insurgency.