Creative Portfolio- An Introduction

When Wilfred Cantwell Smith defined religion as, “an ideology of difference,” I’m not sure this phrase could resound any louder than in the South Asian region. With a population so large that religious minorities account for hundreds of millions within a people, I feared creating a portfolio of creative works might be impossible when trying to represent the immense diversity among these people. In deciding which topics to cover, I debated the questions of what framework of analysis do I try to use when representing this region: one of my own primarily unrelated background, one of a Hindu, a Muslim? But even these terms have a million different definitions depending on the community or the singular person one might ask. I also wondered how do the contemporary ideologies evolving from the rise of colonialism and nationalism effect these different groups perceptions of each other, and who among these groups has the most powerful voice among the public, and among the world’s perception of them. Is it the wealthy Hindu ruling elite, or the working class rick-shaw driver? Is it the wild fundamentalist, the local Imam, or the hijab wearing Muslim woman?

With all of these questions, I realized I could not arrive at just one answer, and that this, in fact, is what should be understood when studying South Asia. There are countless varying and equally as important voices that come together, though often not in unison, to form both the colorful and conflict-riddled region. And in creating my portfolio, I knew I needed to include as many of those voices as I could. Thus, using this “cultural studies” approach, I tried not to focus on just a singular topic in South Asian history, or in current events, but rather consider the influence of both religion and politics as a dynamic and ever changing one.

In discussing the topics of this course there seemed to be contradictions at every corner. Whether it was consideration of Mughal Emperor Akbar as the nation’s hero in India, and the nation’s enemy in India, to scholarly debates among Muslims as to whether visiting Sufi shrines should be considered idolatry, as it is a cultural practice shared by both Hindus and also Muslims, there are not many definitive historical or spiritual narratives to be found. Besides being a land of contradiction, sadly, and perhaps in large part on account of this, South Asia has also been a land of conflict. To follow the vein of this struggle, I dedicated the first section of my portfolio to the theme of “reality and conflict”.

Although there has been war, and religious differences, and forced conversion, and reversing of those conversions, etcetera, etcetera, much of the same issues of violence and of repression of rights still exist in India and Pakistan today in many of the same forms. So to represent this theme of conflict, I found it more powerful to respond creatively to all topics relevant and continuing in the 21st century. The pieces I chose include two set in Pakistan, and the third in India all in relation to physical struggles amongst Hindus and Muslims, and ideological battles fought in the flesh between Muslims of varying schools of thought. The first of these three works is That Question Mark by Ziauddin Sardar offering an insightful look on the problems the young country has encountered politically, economically and religiously, and offering thoughts on how the people can find hope for their continued survival as a nation. Secondly, I chose the expansive work by Farhat Haq covering the struggle for women’s rights in the region: Women, Islam and the State of Pakistan. And finally, now turning to India, I picked the frighteningly honest and eerie work of Rakesh Sharma, The Final Solution, covering and comparing the outbreak of violence in Gujarat to the atrocities of the Holocaust, also using as a second source Jo Johnson’s piece Radical Thinking.

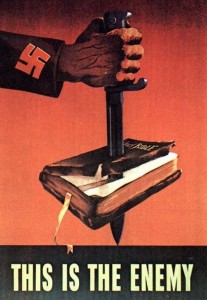

For my work in interpreting Sardar’s essay, what impressed me most was the sweeping nature of his writing and of his interpretation of the story of Pakistan since its birth in 1947. The nation seemed to swing from one regime to another, from modern to traditional, from a complete military state, to one with more freedoms and back again. And through all of this transition, Sardar poses the question that all of us have asked, which is how do they continue to survive despite such odds? He cites a few up and coming hopes of an immerging literary scene, and developing of a cultural identity. I saw the story Sardar tell of Pakistan as one like a musical score, with varying movements, many harsh, yet some sweet. To represent this I wrote a piece for piano divided into three parts, using crescendos and diminuendos to illustrate the successes and failures of the nation. As for the second piece concerning Women in Pakistan, I was struck by my personal yearning, amongst all the historical and scholarly sentences from Haq, for first hand accounts from Pakistani women on what their life is like and what they hope for their futures. So in a creative exercise to feed my own intellectual desires, I made a brochure for a fictional event that could happen at Harvard. The brochure describes a panel of leading female Pakistanis including Malala Yousafzai, Fatima Bhutto, and Riffat Hassan who would gather to speak on “A Female’s Fate in Pakistan”. And finally for the creative piece following Sharma’s The Final Solution, my work turns darker, as I wanted to capture the frightening ties between the events in Gujarat and those in Eastern Europe in the 1930s and ‘40s. So I found a propaganda poster from WWII that I re-drew in the context of the similar radical and violent rallying that took place in 2003 in the Indian region.

Although it cannot be denied that South Asia has had an overarching tide of struggle and conflict throughout their history, equally as steady has been the current of art and literature that has flowed throughout time. There seems to be a theme in the region that always present are struggles, but right by its side are artists either expressing their own opinions and criticisms through words or paintings, or using these same mediums to offer advice or hope to their people. Art can be an instrument of peace. At the very least it is a tool for explanation, a spark to bring about critical thinking among the masses. There are countless examples of the beneficial effects of art such as the aged Sufi tradition of writing songs of worship that lower class people could sing while they worked. One can also cite such famous poets as Iqbal and Bulle Shah. In the case of Iqbal and his critically acclaimed, Complaint and Answer, he succeeded in writing a piece with mass appeal, but which gave critical commentary on his opinion on the state of Muslims while imparting his own more progressive thoughts on his religion. And as for Bulle Shah’s poems, though often times they sound quite secular, they are claimed equally as fervently both by Hindus and Muslims alike. If writers and works such as these have withstood the test of time, and can continue to draw mass appeal from all the differing religious peoples in South Asia, then I can’t help but think there is a great potential for using works such as a means to tear down the walls that have been built up between these communities. Even if overlooking this hope for the future, one cannot deny the power over the centuries of these artistic works influencing the audiences they were intended for, and for helping today’s scholars and students see a picture both literally and figuratively of what the region was like in the days long gone.

Being inspired by the power of this lens into the past, the second theme I chose for this creative portfolio is “interpretation and art”. Where the first section of my work focused on more current times, in order to get the full picture of the region, this half of the project focuses on the past. For the first creative piece, I chose the essay by Professor Asani on The Bridegroom Prophet in Medieval Sindhi Poetry. Both impressed and also confused at first by the style of these writings, I was intrigued by how devotional Islamic poetry was written in the voice of a young woman going to a wedding with the Prophet Muhammad surrounded in Hindu traditions. So in an attempt to see how burning, pious love for the prophet can be expressed in this way I wrote my own poem using the events described by Asani’s essay, entitled “Fire in Medina”. For my second artistic piece I was inspired by the influence of light imagery used in music for religious purposes during the Mughal period, as expressed in Catherine Asher’s A Ray from the Sun: Mughal Ideology and the Visual Construction of the Divine. Following the tone of acceptance that rang clear during this period in South Asian history, I wrote a song in what today would be considered to sound like mainstream Christian acoustic music, but which follows the stylistic themes, specifically light symbolism, used by such writers as Amir Khushrau in Islamic poetry and songs. And to conclude this “interpretation and art” section, I skipped forward in time to the era of partition and the creation of Pakistan. Using the powerful satire on the dividing of these two countries and two peoples: Saadat Hasan Manto’s Toba Tek Singh, I attempted to expand on his criticism of the partition by continuing his short story now from the perspective of Singh’s friend Fazl Din returning just after his death.

It is works like those of Manto and Khushrau that both entertain and also serve a purpose which have been proven to uplift people’s spirits, and tell amusing tales of the moments in time during which they wrote. However even with all of these positive pieces of art and the insightful thoughts they present, art only paid attention to by a small or homogeneous audience will never be enough to effect real change. Indeed there are many conflicts yet to be resolved involving principally religious differences and the problem of “othering”. These issues arose during the British colonization of India, and continue to plague the different sects of Muslims, mainly Sunni and Shi’a, particularly potent in today’s Pakistan. Still it is through the publication of different artistic mediums as well as the rising presence of media outlets that allow the people living among these conflicts to have a voice, and to use that voice to inform others around the world of what they are feeling and experiencing in a very poignant and personal way. Art is a powerful tool for storytelling, especially when the stories are all too real.