For the Love of God and His Prophet was a class that took me on a journey deeper into my inner life. The question, “What does it mean to be a muslim?” was the center of my focus with regard to this class. On a more personal level, it became important to me to know whether it was possible for me to embody the qualities and daily practices of being a good muslim without adopting the title of Muslim. It was also important for me to learn the many diverse ways in which Islam is practiced and affected by culture, tradition, and economy in different parts of the world. I greatly appreciated the cultural studies approach to learning about Islam, as well as the artistic lens through which we learned the daily practices of the average muslim. The blog responses that I have created and presented below represent facets of Islam that I am both drawn to and about which I would like to understand the daily context in modernity.

I examined the themes of: interior design of prayer spaces, Sufi mysticism through Samat dance, modern views on women’s identity through exploration of their thoughts on wearing the veil, love and its expression through poetry, mathnawi narrative through composing epic verses, and the simplification of muslim identity through reflecting on the complexity of my own. In engaging hands-on with these topics through the use of visuals and art, I was able to have a better appreciation for perhaps the greatest theme of the course: that faith is complex because it is socially and culturally embedded, that Islam is a complex religion made even more complicated by cultural factors that have changed the way it is practiced over both time and space.

One of the most important themes significant in the pursuit of any faith and any art or magnum opus is the idea of building mastery through daily ritual. Just as in Koran by Heart, we see children beginning at an early age to participate in Qur’an recitation competitions, it takes a fundamental daily routine oriented towards achieving total understanding of a given subject in order to achieve total mastery of it. The blog posts are only the beginning of my foray into art in the Muslim world. They are basic, bare because they lack knowledge and talent that is refined over time to convey deep meanings concerning the Islamic faith and tradition. However, the act of creating something with the frequency of six times over the course of the semester allowed me to experience practicing the faith to some degree—practicing in the context of arriving at deeper understanding with every piece of art created. Practical or technical application to any abstract concept or theory seems to satisfy our brain’s needs to engage both its cognitive and affective sides. It seems to reassure or reaffirm the truth of one view of the world with the other’s view. By enforcing recitation techniques in younger children, for example, elders in Muslim communities around the world are establishing a foundation of faith in children before they can even begin to comprehend it by asking them to fulfill this less abstract activity. Once children reach the appropriate age in their development, they will discover for themselves the meaning behind the words that they proclaim. Such is the way art relates to this course. The more of it I do, the better I understand and remember the lessons learned from class.

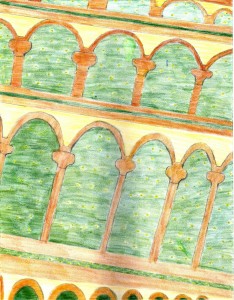

A theme very specific to the prayer carpet I found and drew in the prayer space of Canaday basement is the centrality of God to arabesque design. This is evoked by the choice of this particular carpet design, and most mosque carpet patterns, in that they are all oriented towards Mecca. Walking into the empty prayer room at noon on a weekday, this is the immediate observation that called my attention. To know that entire prayer groups create their formation of prayer as a result of this rule set by faith and carried out by art was both surprising and moving, as the carpet serves as a kind of unifying force that reminds everyone in the room that all are united in prayer under Allah. The other striking feature about this carpet design is the very stereotypical arabesque “archway,” particularly its tip. Its tip, almost always a sharp point that is lifted upwards, parallels the beauty and centrality of the largest dome at the center of the mosque that is also facing upwards towards the heavens. Both serve as a reminder of the light that is Allah and his central role in Islam.

The Samat dance that I learned from watching videos of others perform it brought me to a deeper understanding of Sufi mysticism. Although I am only just beginning to understand how to perform the Samat, I am also beginning to get a glimpse of the ecstasy, divine and passionate love that characterize the Sufi tradition. In Samat dance, one is supposed to lose oneself in the spinning, focusing on a point beyond anything physical, such that the spinning does not affect the individual as typically spinning would do. The greater one’s focus and attention is on achieving transcendence of place with one’s mind, the more settled and balanced the dancer’s posture becomes, almost like a spinning doll. At perhaps the most involved point of the dance, it seems as though the energy of God runs straight through the spine of the dancer, connecting the physical body with the heavens. Though I did not feel as though I reached this point during my own rudimentary experience of dancing the Samat, complete mindful attention towards God is what I strove for. In the moments in which I was most successful at this, my dancing became better, and the spinning became easier to manage.

“Ode to Love” is a ghazal I wrote to better understand the nature of divine love as passionate love and to imagine what a ghazal could say about love itself as opposed to loving an object (in this case, God). Many of the ghazals we have read about through class material seem to be characterized by the intense emotions of a lover being consumed by his love, and in most cases, the pain of not having that love returned. I believe my poem addresses the many questions I have concerning this mode of devotion as being compared to the passionate love between lovers. The questions concern the benefits of sense of conviction of this love that the poet is feeling, whilst at the same time grappling with uncertainty with truth and God himself, as well as the pain of potential rejection. It also speaks to my curiosity as to why poets never wrote about the aftermath of that kind of love and whether that was too dangerous. Nevertheless, writing the ghazal helped me to appreciate how difficult it is to write poetry in couplet form and to express in words the depth of intensity of love described in other ghazals through the use of imagery.

One of the themes that stood out to me from the course was the influence of modernity on the views and practice of Islam, particularly as it relates to the status of women in society. By interviewing two modern Muslim young women—one of whom wore the veil and the other of whom did not—I learned more on what factors, whether societal or personal, are significant in determining whether, when, and how women ought to wear the veil. I learned the dual nature of the veil as being a protective unit for women and in providing that protection the veil itself is an empowering tool, as well as an obstruction to interacting socially and peacefully among the rest of one’s peers. When women are forced to wear the veil, they are stripped of their lack of freedom in needing to put on a full black suite. Nevertheless, the idea that fathers feel more relieved when their daughters put on veils seems to also suggest the hint of good intentions towards women.

The Conference of the Birds exercise was an interesting one because it allowed me to experience writing part of a mathnawi, a larger narrative epic, in which the ideas of every stanza of the piece has to connect to a larger theme. In creating a new character, the raven, for a particular section of the epic, I introduced a new perspective to the chorus of birds. It would have been interesting to compose a part for the raven throughout the whole epic in order to understand the role of a single idea or character changes the nature of the conversation amongst the actors. The Raven symbolically represents an idea that I have not yet found in the context of Islam as studied in this class: through the voices of the other birds, we can see the ways in which we deceive ourselves about our unwillingness to follow God through our capacity to reason (outside the realm of total, passionate devotion to God) with ourselves by coming up with excuses not to journey on the Way. In what situation or story represented in the Qur’an or hadiths do we see ourselves directly confronting our unwillingness to follow the Way, and then to overcome that fundamental unwillingness? In the hoopoe’s response to that direct confrontation that I composed, I could see no way to address this other than by reinforcing the idea that this journey is a choice determined by one’s own free will. I look forward to learning about other opportunities to study Islamic texts in greater detail to understand exactly what Muhammad’s (or Allah’s) answer would be to this question.

Perhaps the most poignant of all themes covered in this class relating to how one understands what it means to be muslim is identity and how one interprets it. The Reluctant Fundamentalist portrays the story of a young Muslim man who pursued and attained the American dream, only to have his identity torn between two different worlds both of which play an integral part of his development. Forced by September 11 to choose a side, he finds Erica, whom he believes is willing to allow him to have both sides of himself. When she leaves, he learns about himself that he cannot completely separate himself from his Muslim identity and uses his knowledge from America to educate his people back home in Pakistan. Thus, Changez is never really one or the other, but both. His character illustrates the complexity of people and their identities. Similarly, this class has taught that Islam also does not stand alone as faith existing in isolation, but that it is one embedded in a society and culture, making it more complex and nuanced but therefore much more widely appealing. In writing a reflection of my own identity for this blog, I recognize that I only acknowledge two aspects, whilst there are also others that also define me. In accepting the complexity of my identity, I hope to discover a way of life that allows me to be fully all of these parts. I aim to never reduce myself to fundamentals and to appreciate the complexity that is human nature embedded in culture and society.

Through these blog posts, I too have embarked on a journey. Whilst it is impossible to know whether I am heading on the Way that leads to the Simorgh, I have reached several conclusions as to what constitutes islam and one who follows it. A muslim is literally defined as “one who submits his will to God”. In essence, a muslim seems to be one who frees himself of his ego to submit himself to his creator. Four of the six blog posts that I’ve created directly concern the idea of submitting the ego to the creator: this is seen in the tips and directionality of the design on the carpet, the transcendence of self through Samat dance, the Raven’s dilemma, and the ghazal that speaks to the all-consuming love for God. The other two posts concern the ego and questions of identity very directly in exploring women’s place in society as well as a muslim’s place in the world. While the first four representations of art speak to the submission of the ego as already having occurred, the latter two describes the struggle of letting the ego surrender to God, or the greater picture.

Can I then be a muslim? Having actively participated in understanding muslim identity in creating this portfolio, it seems as though I am at a stage in which my ego is still questioning itself, but is beginning to submit to a greater power, which I believe to be God. Should I complete this process and continue on this journey, I may be muslim after all.

After watching The Reluctant Fundamentalist, I found myself asking, “how do I come to know who I am?”

I used to believe that the fundamental pillars of my identity boiled to faith and culture. As a Christian South Indian, it was difficult to find a community, place, or environment that could relate to both sides of me. I would learn the theory of my faith through lessons at church whilst spending most of my time and energy practicing Indian Classical Dance lessons–an art form that finds its roots in another faith but taught me much of the mythology, folklore, traditions, and music that make up my cultural heritage. It seemed as if I would have to make a decision eventually to choose a life that leaned heavily one way or the other because these two worlds of mine hardly never met.

I could feel the internal struggle of Changez living the American dream by working at Underwood Samson but needing to shave his beard and going home to his father’s disapproval of how he lived his life. The divide here seems also to reflect the tension between Changez’s Muslim faith and his desire to fit into American culture. When Changez found what he thought was acceptance of his part American, part Muslim identity in Erica (I found it curious that her name is the last five letters of the word ‘America’) up until he realized that she did not understand him at all, he was quite content with his life.

Events and interpersonal relationships seem to hold much influence on the decision to swing to either side of one’s identity. Between my sophomore and junior year, in the midst of my existential struggles to find God, I met two friends in my life that caused me to swing from participating in all cultural activities to all works of service. I was so inspired by the idea of living my faith more fully through action that I completely changed my extracurricular interests, thereby coming to disregard the immense value of the cultural tradition I was born and raised in.

It is only now that I’m realizing the age-old truth of the saying: people are complex. The moment I began to fully embrace both sides of my identity, and realized that faith and culture were just two of many parts to my identity, it became easier to fit into any society, group, or social structure–but this time, as an individual. It does not do to simplify the parts that make up who I am; it is much better to accept all parts of me so that I can begin to live as an integrated whole.

Identity is not just about the fundamentals; it is about the complexity that is human nature, as well as the ways in which we come to understand these parts. Just as with Changez, this requires a journey of some sort in order to fully appreciate myself to the fullest. After the identity crisis is solved, one can then begin to live and give back to the world more fully.

The Raven’s excuse

The Raven approached with confidence in his stride,

His manner seeped in nothing short of pride,

Crowing: “I’ve already journeyed to the Simorgh alone,

I’ve been welcomed into the presence of His very throne.

Fair friends, what the hoopoe spoke is entirely true,

His sight alone is enough to fill you with joy anew.

After spending time in His esteemed presence,

I began to miss my very essence,

And yearned for the soul I once had

That I lost it on the journey made me incredibly sad.

The almighty Simorgh saw me and understood,

He gave me the option of leaving him for good.

I bade Him farewell and thus stand before you today,

Perpetually lost and forever stuck on the Way.

To be eternally content in this restless dismay and disarray.

The hoopoe answers him

The hoopoe’s eyes filled with tears,

The words of the raven confirmed his worst fears,

That those who held the privilege of knowing His Grace

Could choose to turn away from His face.

To the black bird’s words, therefore, he had only to say

To the others: “It is entirely your choice this day

To journey to the Simorgh together with the rest

Or to make the quest alone another day at best.”

One of the sections of The Conference of the Birds that was discussed in section was the part in which each bird that had gathered around the hoopoe after he encouraged and welcomed all to journey with him to see the Simorgh and gave an excuse as to why they could not accompany the group on the journey. Each of their excuses (wealth and riches, for example) represents a vice that keeps them from journeying on the Way to see the Simorgh, who represents God. To this collection of vices/excuses, I felt compelled to add another voice: the voice of one who had seen the light of God and actively chose to reject it–in other words, sin or evil at its purest and most intentional form. While in extreme interpretations of Islam, the love for God seems to have been used to justify jihad, I wonder whether there is any advice or admonishment given to those who actively seek to not love God and commit crime intentionally without reason. In completing this exercise, I’ve come to realize that I do not know anyone without at least an ounce of goodness in them or who would prefer to operate in this way. Thus, my only explanation for the existence of evil in this world is misunderstanding of goodness and what it can offer.

I was curious to see how Muslim women on Harvard’s campus thought about the issue of wearing the veil. I decided to interview two of my friends. Sufia Mehmood is a sophomore who chooses to wear the veil. Mahi Mahmood is a senior who chooses not to. The following are the interview questions I asked and their replies.

Mahi Mahmood, ’16

Do you wear the veil? If so, how often do you wear it? Is there a particular way/style in which you wear yours that is unique to you or your family?

I don’t wear the veil. To be honest, I didn’t even consider wearing the veil until I was in college. Growing up, no woman in my family had ever worn the veil. In recent years, when I’ve questioned why that is, my mom has attributed it to the fact that higher class Muslims in Pakistan are often exempt from the societal expectations that others might be more stringently held to. It’s unclear to me though whether my family’s distancing from religious tradition was a result of their status or if it’s something that has long existed.

Lately, however, I’ve been feeling more and more drawn to the idea of wearing a veil.

Because it feels like such a permanent commitment, however, I must carefully think through this decision: Is it something I can commit to for life? What does it really mean to me to wear a hijab? What does it convey to others (muslim and nonmuslim)? I’m very much still in the process of trying to answer these questions for myself.

Why do you (specifically) wear the veil? Why do Muslim women more generally wear it?

In my opinion, the hijab is, for many women, a method of self-empowerment through modesty. To me the idea of wearing a hijab is not only about the level of religiosity that is often associated with it, but also about making women feel like they have greater control/ agency over their bodies by limiting the people in their lives who have access to it.

We read in class about feminist writers, poets, and other artists about opposition to wearing the veil because it limits women’s freedom and identity. Do you agree/disagree and why? Or, what is your response to this?

I disagree with this sentiment completely. Wearing the hijab is, for many women, a component of Muslim feminism. Opposition to the veil should exist only if women are being unjustly pushed to it; however, in my opinion, these cases are rare. Often, women opt to wear the hijab because they believe it reflects values that have been important to them in their life, community, etc.

Does the veil ever prevent you from doing something you really wanted to do? Has it saved you from any situation you didn’t want to be in?

N/A.

Do other women in your family wear the veil? If yes, is this an expectation?

Answered above.

What does being Muslim mean to you?

This is a question I have struggled with for quite a while. Although I personally consider myself to be quite religious, I often hesitate to make that claim boldly. This is because I am not a very “practicing” Muslim; I drink and party, don’t wear the hijab, and don’t pray namaz often.

However, I would push back on this concept of being a “practicing” Muslim and argue that I practice Islam every time I volunteer, take the time to make someone feel better, do a random acts of kindness, or even just take in the beauty of the world around me and praise His creation. To me, these things are the defining characteristics of a Muslim. The rest of the components (abstinence from alcohol, modesty, prayer, etc.) although important, are not necessary, in my opinion, for one to demonstrate their submission to God.

How do you define your identity? What does it mean to be Mahi?

There are many components to my identity. I am a Muslim woman, a first generation college student from an immigrant family in the lower range of the socioeconomic spectrum, a biologist, a Pakistani, a Harvard student, a middle child, and so many other things. Identity is something that is incredibly fluid in my mind- different parts become salient in different contexts. It’s difficult, then, for me to pinpoint exactly who I am.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Sufia Mehmood, ’18

I asked Sufia the same questions as above. The following is her answer to all the questions collectively.

Firstly, we should probably say that the one I wear is called a hijab, not a veil…veils are the ones that would cover the face. I wear it daily. There are multiple styles, but for me personally, I just sewed it with a hole for the head spot lol, just to make it easier so I don’t have to tie it every day. No one else in my family wears it.

I wear it because my dad asked me to. Simple as that…he said it would just make him more comfortable while I’m at college. And I was fine with that compromise as long as I was able to come to college.

I feel like generally each woman has their own reason why they wear it. If you’re asking from a religious standpoint, it’s meant to be so the woman is completely covered around men that are not “mehram,” which just means men that aren’t immediately related to them (brother, father, husband). Male cousins are non-mehram because it is valid to marry first cousins I guess, so some sort of non-familial attraction could ensue between them, whereas that isn’t the case with father or brother.

I don’t think it limits a woman’s freedom and identity as long as she is okay with wearing it. If it is forced, then maybe. But even in my case, just because my dad said he’d feel more comfortable if I did wear it didn’t mean that I had to. I’m over 3000 miles away from home. It was my choice. And I don’t think that it’s limiting because I chose it.

I’ll admit that though I do control whether or not I wear the hijab, I can’t control how others react to it. And there definitely have been situations where I’ve been treated or perceived differently because I was wearing the hijab. I remember one time distinctly when I was just walking down the street in Somerville. A little girl dropped some stuffed animal toy thing, and I picked it up and gave it back. I got a smile from both her and the mom and a thank you. But then, as I was walking away, I heard the little girl ask her mom what the thing I was wearing on my head was. And the mom’s response was, “It’s something that means they’re the bad guys. And bad guys hurt people. So we need to stay away from them.” It hurt, sure. But I don’t have control over what others think or say, and it’s not something that stopped me from wearing the hijab.

My identity…I don’t know. I think that’s still something I’m figuring out for sure. Family. School. What makes me me is how I interact with those around me, the things that make me happy…I don’t know. That’s hard. But I’d definitely say that I don’t think my religion defines me. Each person has a different perception of their relationship with their religion or lack thereof…I personally don’t feel like that’s something that should define my identity. It can be a part of it along with other things, but not wholly that.

Ode to Love: Ghazal of Ghazals

Happy is the small moth who catches sight of a brilliant candlelight in the distance

And, moved, flies straight towards it only to get singed by its flame.

Nevertheless it strains to stay near the fire’s warmth.

How easy it is for a small kitten to be consumed by a ball of yarn,

To be fixated on unraveling it to its empty core.

Likewise I am consumed by the pursuit of elusive love

Believing myself to be following a thread but never really knowing whether it’s real.

It does not matter whether the thorn falls on the leaf or vice versa,

A hole still gets made and both must address the change.

The feverish devotion of a poet to his inspiration begets art—just so,

Sreeja seeks relentlessly the secret to God’s works and finds unconditional love.

Because I chose to recite a ghazal in Persian for the Ghazal project, I felt curious to try my hand at writing my own. Like other ghazals, mine is about love in its devotional, ecstatic form. Unlike others, however, I tried to capture some of the consequences or results of pursuing such a love, whether it is expressed to God or another human being. The first and fourth couplet speaks to the strain or pain of seeking and finding passionate love. The second and third couplet speaks to the great uncertainty or potential for disillusionment that accompanies one consumed by passion. The last couplet speaks to the best possible result that could happen whilst one pursues passionate love–that, regardless of whether it is found, one finds the ability to love without condition. The overall message is: as we ought to be consumed by passionate devotion toward a God we cannot see, the resulting pain and despair causes us to turn towards those whom we can see and love. It is this kind of love without return towards those we can see that ultimately brings us to Him and quenches our passion.

I grew up learning that dance is a mode of conveying culture, tradition, folklore and spirituality to an audience. The goal of dance as described in the Indian Classical Dance, which I learned for thirteen years, is to deeply move the audience. In my time as a dancer, I’ve had only one occasion to feel the ecstasy of transcending the space and time I was a part of, and that was after many years of training. In the short 15-minute period before this was being shot, I learned what samat, or sufi dancing is supposed to look like, though I have a long way to go in terms of training and understanding Samat dancing in its entirety. I look forward to the liberating feeling of transcending the physical aspect of movement to reach the spiritual dimension of dance.

Muslim Student Prayer Space & Carpet Design

Muslim Student Prayer Space & Carpet Design

This is a color pencil depiction of the carpet pattern of the Muslim prayer space on campus. Just as in the standard mosque, the carpet pattern is such that the tops of the archways point to Mecca, indicating the direction in which people are to be facing during prayer time. I was told by a Muslim student who was sitting in the prayer space when I went to take the picture that even in this space, men gather in rows and pray with the women following suit at the back. Apart from this carpet, which is as magnificent and colorful as the ones that are found in larger mosques, the prayer space is rather empty. The space is painted a gray-white color that reflects light around the room. The room has 2-3 windows though which sunlight is greatly visible and people’s faces are illuminated by that light because of where the windows are in relative position to the direction in which people are facing when they pray.

The prayer space also functions as a center for HIS students to gather in small groups and for students to come in and study, thereby serving as a community gathering place as mosques often do.

Welcome to Weblogs at Harvard. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start blogging!