Wikipedia’s copyright January 5, 2008

Posted by keito in : Wikipedia , comments closedToday, stories of high school students pasting in content from Wikipedia into their own essays and research projects abound. Some educators have thrown their hands up in the air, baffled by this whole “Internet” thing. Others have clamped down, forbidding the use of Wikipedia in the classroom and calling it an irrelevant information source.

While this plagiarism from Wikipedia may seem like child’s play, serious legal issues also play a part. As I’ve covered in this blog, Wikipedia content is not released into the public domain — by default, all content is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License, and the copyright remains under the ownership of each contributor.

This is further complicated by the fact that some contributors choose to unilaterally license their contributions under a freer license, such as into the public domain. Some users have also chosen to “dual-license” their contributions, under, say, the GFDL and the CC-BY-SA. These license indications are not shown on the contributions themselves; each user who decides to do this usually places this information on their “user page.”

There have been a number of cases in which individuals or groups have lifted Wikipedia content without attribution of any kind, essentially committing copyright infringement. One recent case was the case of George Orwel (sic.), a New York-based reporter who pasted a substantial amount of content from a Wikipedia article into his book, “Black Gold: The New Frontier in Oil for Investors.”

What complicated this matter was that the user who contributed a large portion of the text, Ydorb, had licensed his contributions into the public domain. Therefore, it would seem that this act of “plagiarism” was, in fact, lawful (albeit troubling coming from an experienced reporter). However, the nature of Wikipedia’s collaborative and cumulative editing meant that portions that had been contributed by other users, who unlike Ydorb had not released their contributions to the public domain, were still under their copyright. This is an issue present in all wikis — because content is not simply written by one user and left at that, the ownership of specific bits of text, rather than entire articles, becomes important.

While it may be easy for people (even reporters) to become complacent about Wikipedia copyright, the bottom line is that every contribution to Wikipedia is still covered by the same copyright that automatically covers any other creative work. A free license is not a license to do whatever you want; there are certain bounds, and users need to be educated about this.

Wikipedia and CC-BY-SA January 1, 2008

Posted by keito in : Wikipedia , comments closedIt’s been nearly a month since the Wikimedia Foundation announced compatibility of the CC-BY-SA license with the GFDL, but the details are still not clear.

Immediate reactions on the Wikimedia Foundation’s community mailing list, foundation-l, seemed positive overall but rather confused. Users wondered whether a license like CC-BY-SA and the GFDL (both of which have a “Share-Alike” clause, which essentially says that copies and derivatives must be made available under an identical license), could be made compatible, and whether a license switch would be legally enforceable. The latter is not an issue, as both the CC-BY-SA and GFDL contain clauses permitting the controlling bodies to upgrade the licenses without notifying licensors. There is precedent for this; for example, the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s now-defunct Open Audio License designates version 2 of itself as the CC-BY-SA license.

Members of the community were further confused by the inherent compatibility of the two licenses; the GFDL allows invariant sections, for example, which, they argued, is against the spirit of the CC-BY-SA license. This hasn’t yet been adequately discussed — even if it is legally possible to create a variant middle-ground of the two licenses that is compatible with older versions of both, that risks estranging content owners who published their content under a previous license. (Those using the invariant clause of the GFDL, for example, may not appreciate having even those sections licensed freely under a CC-BY-SA-like license.)

Since the actual process of conversion is taking place within the Free Software Foundation and Creative Commons, it’s not immediately clear to the average Wikimedian what is going where. My personal hope is that the two organizations will be able to come up with a new license that legally transitions existing GFDL (with no invariant sections) materials to CC-BY-SA in the not-so-far future. I also hope that people who have contributed content to Wikipedia in the past will be happy with the change; this should not be too much of a problem, since (1) most people do not really care about licenses and (2) the people who do care, or at least those who have voiced their opinion on foundation-l, appear to be in favor of a change.

There are some outstanding issues that have yet to be resolved though — those detailed above, and some issues to do with the Creative Commons organization itself. More than one longstanding Wikimedian has expressed his displeasure at the organization, calling it an organization whose purpose is for lawyer collaboration and self-promotion more than for the spread of free content. While I cannot tell if this is true, having no personal dealings with the organization, Creative Commons is rather successful with its public relations, so it’s not hard to imagine them worrying a lot about their public image. However, the overall effect of the Creative Commons movement, it seems, is overwhelmingly positive, and Wikipedia’s joining forces with them seems like a promising move (and as some members of the Wikimedia community mentioned, it also means that the Wikimedia Foundation will have a lot of leverage over the organization).

Wikipedia and the GFDL January 1, 2008

Posted by keito in : Wikipedia , comments closedWikipedia, since its very inception, has used the GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL, covered in an earlier post) to license its articles and many of its images. Compared to other, more traditional websites that offer their content under a less free, less open license, this is a big step — and it’s not an overstatement to say that Wikipedia exemplifies, if not leads, the whole gamut of user-contributed websites today. What does the GFDL mean for Wikipedia?

First, how exactly is Wikipedia content licensed? Here is the official license text from the Copyrights page:

Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts.

As you can see, Wikipedia does not use the controversial Invariant Sections clause that the GFDL permits — that means there are no pages on Wikipedia detailing its philosophy that must be kept in derivatives (such as other websites that reuse Wikipedia content).

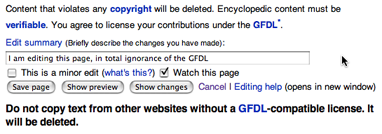

What does Wikipedia’s license mean for the average contributor? When you goto a Wikipedia page, hit “Edit this page”, make your changes, then finally hit “Save page”, you are licensing your contributions under the GFDL. This is because the edit page, similar in spirit to “clickwrap” licenses found on the Internet and in software, contains the text, “You agree to license your contributions under the GFDL” along with a footer with the text quoted above.

Now I expect that the average visitor to Wikipedia who makes a quick contribution (such as a spelling fix or changes some figures here or there) does not realize this fact. This might be a little problematic for Wikipedia, as there is no “I agree” button, or any other user interface element (such as a checkbox) that forces the user to agree to this license. In the past, the courts have found this to be a problem — in Specht v. Netscape Communications Corp. (2001), the court ruled that the Netscape license was not enforceable as there was no explicit “I agree” button for the user to click before downloading the software. The changes needed to ensure Wikipedia’s safety might be minimal — simply by preceding the text with ‘By clicking “save page” below, you…,’ for example. It would be interesting to see whether this is actually a problem legally.

What, then, does the GFDL mean for the established Wikipedian? Firstly, it means that there’s a slight learning curve — getting accustomed to the GFDL and the various restrictions and freedoms it poses is something that can only be learned through reading through the rather thorough documentation on Wikipedia itself. Second, it means that a lot of care must be taken to preserve edit histories.

Edit histories are the information you get when you click on the “History” tab of an article on Wikipedia; basic information about each revision to an article, such as the user name (or IP address, in case of anonymous contributors) and date and time of each revision, are presented. This list is necessary for copyright purposes; because Wikipedia articles are not copyrighted by the Wikimedia Foundation, or any other single entity, but by its contributors (due to standard Berne Convention rules), the list of contributors must be preserved throughout revisions in case somebody wishes to relicense an article (although this is unheard of as of yet) or more frequently, an article needs to be cited.

The preservation of edit histories is usually carried out automatically by the MediaWiki software; however, when merging two pages into one, for example, the origins of each portion of text must be noted on the attached discussion page of the resulting article.

Of course, this preservation of edit histories is not a burden associated exclusively with the GFDL; any Creative Commons license requiring attribution would also have the same burdens.

It turns out that the real restrictions of the GFDL (as used by Wikipedia, without the invariant sections clause) are only in the redistribution stage, the requirement to include the full text of the GNU Free Documentation License along with redistributed copies being the main one. Even if this is the only problem, it is a good enough reason to switch Wikipedia’s license — switching to a Creative Commons license will greatly increase the utility of Wikipedia content.