Post Four

Same Mosque, Different View

(Week 6)

The mosque is one of the most widely recognized and prominent symbols of Islam and of the devotional lives of Muslims. Throughout the centuries, central features of the mosque have remained constant (such as the Qiblah, mihrab, and minarets). However, the décor and aesthetic aspect of mosque design and of “Islamic art” in general, as well as its interpretation by artists, historians, and laymen, have varied across time and space. One of these debates centers around the definition of Islamic art – what makes art Islamic? Is the category of “Islamic art” a real, unified phenomenon, or a reification of several abstract concepts that vary by context? Nasr argues that art is indeed a real, unified manifestation of religion. He claims that Islamic art is unified by pieces all tracing back to an origin of inner realities (haqa’iq) of the Qur’an, and therefore static in meaning across time and context. As such, a work can only be considered Islamic if it was inspired and given by God directly to the artist, or relayed to the artist from a person to which God revealed an artistic inspiration. Nasr offers, as one piece of evidence for the inner origin of Islamic art, the way the rites connected with it “mould the minds and souls of Muslims,” which nods to the Sufi emphasis on the esoteric rather than exoteric meanings of the Qur’an and the Islamic faith in general.

On the other hand, Necipoglu believes that the definition of art as “Islamic” is dependent on context and not universally interpreted in one way. Instead, art is defined by politics and therefore open to more people than just Muslims with esoteric knowledge (e.g. Western scholars and historians). She maintains that when it comes to Islamic art, it is better to assign contradictory meanings to the same piece than for it to have no meaning at all, and that the meaning as “Islamic” is dynamic across time and space. She directly pushes back against Nasr’s opinion when she says, “The implication that Muslim believers are better equipped to penetrate the inner meanings of their own visual cultures assumes that the past is more transparent to them. Since all interpretations are bound up with one’s own historicity, however, it is difficult to believe that any interpreter, from whatever background, is more privileged with objectivity” (p. 79).

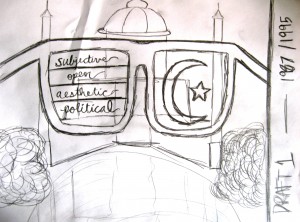

This pencil sketch incorporates both sides of this art debate represented by the arguments of Nasr and Necipoglu. The sketch is meant to be a draft sketch of what the artist will later turn into a work of art (as noted on the right by “Draft” and label number 1987/1995, which are the years that Nasr and Necipoglu, respectively, published their art commentaries to which I refer), since much of the debate on whether a piece is “Islamic” is in the artist’s intentions and background/context. A mosque, one of the most prominent and recognizable symbols of Islam, is depicted in the background. The viewer, however, can view the same mosque (the same reality, the same creative work) through two different lenses. In staying with Nasr’s viewpoint, the lens on the right overlays the star and crescent, a symbol of Islam, onto the whole scene of the mosque, which represents the connection to the faith and Qur’an that must underlie art to make it Islamic according to Nasr. As for Necipoglu’s viewpoint, the lens on the left is layered with different adjectives – “subjective, aesthetic, open, political” – to represent that the same piece can have many different layers of meaning and many different interpretations, depending on context.

Recent Comments