Introductory Essay

ø

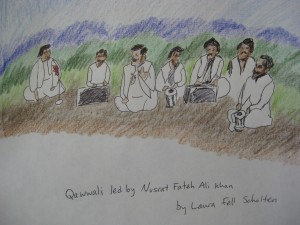

I created this artwork in the spring of 2014 to express themes studied in an Islam through the arts class taught by Professor Asani at Harvard University. I am not a professional artist, but enjoyed the opportunity to express myself academically through the arts for the first time in several years. The course was 13 weeks long, and each week’s readings, class lectures, and discussion sections contained several themes expressed through Islamic art, architecture, and culture. The structure of the class was non-linear, and the themes did not build off of one another like blocks, but rather functioned independently as part of a vast cultural web or landscape. The themes that I chose to illustrate through colored pencil drawing, collage, cartoons, poetry, personal essay, and photography were: Geometric design in Islamic architecture, Taziyeh: Iranian passion plays celebrating the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, Light: a trope in the Qur’an and Islamic art representing the divine, Qawwali: A form of dhikr (Sufi music and/or dance), Feminism in Islam, and the Experiences of Contemporary Muslim Immigrants in the United States.

The central point of the first few classes was the fact that there is no single “Islam” and that “Islam” does not say or do things. Similarly, “Islam” does not have singular opinions or universal rules. The only central belief common to all geographic expressions of Islam is the Shahadah: “There is no God but God, and Muhammad is his messenger” (plus an additional phrase about Ali if you are a Shia Muslim). We also learned that various forms of Islam have five or more “Pillars”. The most common five are reciting the Shahadah, performing the “salat” prayer five times a day, giving “zakat” alms to the poor, fasting called “sawm” during the month of Ramadan, and going on the “hajj” pilgrimage to Mecca.

The class was intentionally taught using a Cultural Studies approach. This means that we studied a variety of aspects of Islamic art, architecture, society, and culture through the lens that everything is interconnected, and culturally specific to the region in which it appears. A common critique of the Cultural Studies approach is that the course felt scattered and inconclusive. A common praise of the Cultural Studies method is that we were exposed to a wide variety of cultural expressions of Islam through readings, multimedia, and lecturers, in order to appreciate the vast diversity contained within the religion.

As a student studying Islam for the first time, I appreciated the Cultural Studies approach and felt it was a successful way to gain an introductory appreciation of the nuances of such a complex topic of global importance, without oversimplifying the religion into generalizations. As a student minister of a local Unitarian Universalist church, and a student at Harvard Divinity School studying to be a Unitarian Universalist minister, I appreciated the emphasis the course placed on multicultural experiences of similarity and difference, interfaith communities, and geographic variation in worship, art, and culture.

I believe that studying the Arts of a religion, country, or identity group is an effective way to learn about their history, culture, and beliefs. Arts are simultaneously local and universal. They are “local” in that they express the history and culture of the specific place and context for which they were created. On the other hand, the beauty of the Arts speaks a universal language, which transcends nationality, religion, race, gender, politics, etc. You do not have to be a Muslim to appreciate the beauty of Islamic art and architecture, including the beautiful song, dance, architecture, mosaics containing passages of the Qur’an, poetry, novels, or film. I am not a Muslim, yet I could experience spiritual transcendence while listening to Pakistani Sufi Qawwalis, which I discuss in a post on this blog. This class was a special opportunity for me to experience for the first time a wide variety of Islamic art, learn about its cultural context, and admire its beauty.

The central theme of the course which I touched upon in my last blog entry is the idea that Muslims believe there is only one God worshiped by all monotheistic religions (Judaism, Christianity, sometimes includes Hinduism), and as a result many Muslims are tolerant of other religions. This was a major theme of many of the multimedia sources we watched, read, and listened to in the class, such as the film New Muslim Cool, and stood out as a source of optimism and hope for the future of our politically-divided world. We kept returning to the idea that Islam has a long history of tolerant, moderate, and progressive relations with interfaith communities of friends and neighbors of other religions. Fundamentalism and Extremism were portrayed as fringe elements and anomalies in the class, products of recent Islamic politics in the Middle East and the rise of Saudi Arabian influence. (Such as in the film Koran by Heart, for example.)

As a student minister of an interfaith religion in which members can be atheists, agnostics, pagans, Buddhists, Hindus, Christians, Jews, Muslims, etc. I especially appreciated the attention given to the history of Muslim tolerance, liberalism, and progressivism. Respect for other religious traditions is one of our core Unitarian Universalist values, and I was happy to see that it shared by many Muslim communities worldwide. All to often Islam is given a bad reputation in the West by people (media, politicians, etc.) who overestimate the significance of Islamic fundamentalists, extremists, and the small group of Islamic terrorists compared to the vast array of different types of Islamic liberals and moderates. It is my hope that more people in the US come to see Islam for the various and diverse religion it is, and come to know Muslims as individuals within geographically and culturally distinct groups, as opposed to stereotypes and generalizations. In this way I hope the culture of blatant Islamophobia in the West, and in the United States in particular, can evolve into an atmosphere in which moderate and progressive Muslims and Muslim communities are accepted and welcomed.

The first blog post I did was one of the most meaningful for me. In it I wrote a poem to express my reaction to studying patterns (geometric, floral, etc.) in mosque art and architecture. In my poem I treat my house as a mosque, and analyze its patterns of design to see what meaning the art and architecture of my house conveys. I found that my house is covered floor to ceiling in patterns drawn from nature, essentially making it a temple for the worship of the unity of the pattern/design that pervades the natural world. This is especially appropriate because my fiancée and I are farmers and stewards of conservation land. We both value nature above all, and it was a profound realization that our house, which was not decorated or furnished by us, but by previous generations, matches our values and beliefs. Coincidence? Maybe. Or maybe this consciousness frozen in the art and architecture of the house is actively passed down through the generations through oral tradition, lifestyle, and local culture. Or maybe it is just an extension of the environment on which the house is situated, the values and beliefs a natural consequence of living on such a beautiful piece of land. Writing the blog post prompted me to see my surroundings in a whole new way, in light of the cultural studies approach. From now on I will consider what the specific art and architecture of a place says about the values and beliefs of the people who built it and/or live there. Often times the things we worship as a culture are reflected even in the design of our supposedly secular spaces.

Another theme of the course that struck me was Feminism in Islam. Unsurprisingly, Islamic feminism comes in many culturally distinct forms, such as were expressed in the graphic novel Persepolis, satirical story Sultana’s Dream, and poem “We Sinful Women.” I was surprised by the theme that women who wear hijabs can be feminists, and wear the hijab as a reclamation and statement of their identities as Muslim women. I was raised to understand that the hijab was a marker of patriarchy’s sexual suppression of women in conservative Islamic communities. As such, it took me a while to get used to the idea that Muslim women who wear the hijab could think of themselves the same way Muslim women who don’t wear the hijab think of themselves, and/or the same way non-Muslim women think of themselves. The hijab may have been a product of a male-dominated society and enforced by patriarchy, but it has become so much more. It has become a politically-charged signifier and tool for female religious and/or political expression. While I still believe it should be a woman’s choice whether or not to cover her head, and not a government’s mandate (for or against), I learned from the various multimedia in class, especially films and interviews, that women’s clothing means different things in different countries, and is a more complicated subject than I had originally thought. For this reason I made a character in one of my blog posts a woman who wears a chador, a conservative article of clothing for a Muslim woman, but who expresses feminist values in other ways, through her actions and speech.

I believe that one of the best ways to learn about Islam is to interact socially with Muslims in your local town or community. Meeting and getting to know Muslims from three or more countries and as many US states taught me how important regional differences in Muslim cultures are, and how diverse the religion of Islam is. My fear of people in Muslim clothing decreased dramatically after I made Muslim friends. This is the case with any ethnic, racial, religious, etc. minority in a city, state, or country. People naturally fear what they do not understand. I think that intelligent films and documentaries about Muslim cultures such as the ones we watched in this class can help non-Muslims understand and relate to their neighbors. Intercultural understanding is a first step towards acceptance and peace.

One could make the generalization that for hundreds of years, Catholics and Protestants feared, discriminated, and warred against each other, Jews were oppressed and attacked by Christians, etc. Now it seems like the problem of the decade is religious conflict in the Middle East, between such groups as Hindus and Muslims, Muslims and Jews, and between Muslim communities and the predominantly Protestant Christian United States. I wrote a blog post about learning from my Moroccan friends who are Muslims for this reason. They taught me to be more open-minded about cultural difference, and more importantly, to start to see cultural similarities between us. This class taught me to appreciate the geographic and cultural diversity of Islam, and to start to see the universality of its central faith in God. I was left feeling hopeful about the potential for reconciliation between the US and the many Muslim communities worldwide.