An Introduction to “Identity Juice”

Tuesday, December 9th, 2014** NOTE: The introduction written below can also be found by clicking the following link: Introductory Post

———————————————————————————————————————————

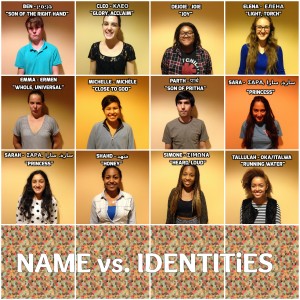

When looking back at the start of this course in retrospect, what I find stunning is how naïve I was. Over the course of the past twelve weeks, our class has discussed a variety of themes that all sort of fall underneath the same umbrella, albeit every single theme is individual and distinct in its own way. At the start of the course, I was familiar with these topics – the importance of identity, for example, and other topics that we’ve been exposed to for a while now, such as stereotypes and prejudice – but I realize now that I was naïve about the complexities of these issues. I knew, for example, that I identified as an Asian American, middle-class young adult. Coming in, this was my sole identity wrapped up in a package, presented to everyone I met in a straightforward way, and this was what I saw myself as. I knew these unique characteristics, these special qualities that made me different, but as far as the superficial world was concerned, my race, age, and socioeconomic status was what I was defined by. Now that we’ve approached the end of these past twelve weeks, my views on this topic have changed immensely; with every reading that we’ve done and every discussion we’ve had, my mind’s been opened in a way that’s allowed me to view myself not by the identity that society has put me into, but by the multifaceted dimensions that exist within myself and within every human being. This, among other things, has been one of the primary themes that have stuck out to me throughout this course and through the readings, and the importance of these different themes will be emphasized in each of the blog posts below.

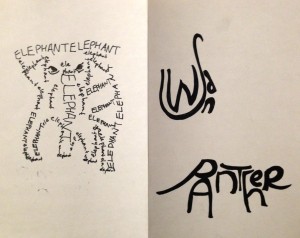

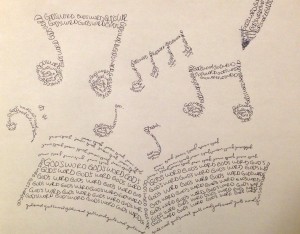

I’d like to start off by giving a general introduction to each of the ten works that I created in this blog. The ten works cover ten separate readings that we completed this past semester, and also involve a variety of different mediums; for example, in the fields of visual arts, I experimented with oil pastels, pen and paper, pencil sketches, digital photo shop, and photography, and in the fields of writing, I dabbled in poetry, creative writing, and even screenwriting. My oil pastel work was a parody of Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon” album cover; although it didn’t turn out the way I wanted it to, I thought it definitely exemplified the theme of many different entities having a single origin – in this case, the three religions of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism represented by the different spectrums of visible light that are reflected through the prism. My pen and paper work required a lot of creativity as well, although I definitely needed some practice before I could actually create what I wanted. In class, we had viewed several examples of calligrams, or visual designs or drawings done using intricate and beautiful Arabic calligraphy. I found out, however, that calligrams didn’t necessarily have to be in Arabic; as a result, I Google searched some images of calligrams done in the English language, and then created my own calligram that emphasized the beauty of God’s word in a visual form. My pencil sketch, similar to the oil pastel work, was also inspired by another “classic,” or great work – this time by Oscar de la Renta, a world-famous fashion designer who just recently passed a few months ago. I chose to relate the pencil sketch to “We Sinful Women,” an anthology of poems written by famed Muslim poets that included many works detailing the frustrated feelings of women who were oppressed and stifled based on the clothes they chose to wear or the shapes of their bodies. In this case, I chose to sketch out two fashion designs – something that I had never done before and actually found quite fun – and then used the sketches to reflect the criticisms and unjust name-calling that are often thrown at women for incredibly superficial things, such as their clothing.

What I really enjoyed, however, were the works of writing that I got to do. I feel like I’ve always been more of a creative writing type of person rather than someone who was more visual arts-oriented. In middle school (way back before my life had gotten consumed by schoolwork and extracurriculars and such) I would spend a lot of my free-time writing short stories, poetry, and fictional narratives; now that I had the opportunity to go back to that pastime, I found myself feeling incredibly apprehensive about sitting down and actually writing a story again. It seemed like such a hassle, a huge hurdle that I was making myself jump through. When I finally sat down at one of those metallic tables outside Memorial Church, however, and faced Widener Library in the midst of the autumn leaves floating down around me, the process of writing came as naturally as it had all those previous years. My first piece of writing was an untitled short story, something that was vaguely drawn from my own experiences as a growing adolescent who was conflicted by my own identity. More specifically, it involved an unnamed character and his final meeting with his high school guidance counselor, and the subsequent game of chess that reveals more about not only the relationship between the two characters, but the reasons as to why the student had been meeting with the counselor for so long in the first place. My other pieces of writing are a collection of five haikus, which I wrote in response to “The Swallows of Kabul” and which emphasize the theme of mob mentality and the power of fear, and a short screenplay of a one-scene, one-act production entitled “[Insert Title Here]”, which I hoped would represent the fluidity of identity and how society’s external standards and perceptions often affect how people perceive a certain individual, even without his or her consent (this theme I drew from “The Reluctant Fundamentalist”).

All of these creative responses seem to envelope themes that are encompassed within a certain “umbrella” of themes, if you will; while the themes discussed through the readings – the power of fear, the intersection between science and religion, and religious pluralism, just to name a few – are each distinct in their own ways, they can also be grouped together pretty clearly. Some readings, for example, are very strong in their themes of multifaceted identities. This type of identity, I have realized, is not strictly limited to human beings. Certainly, we can talk about every human having a identity of many different sides. In “We Sinful Women,” for example, one strong message that is delivered is that a woman – just like any other being – should have the ability to think for herself and be defined not by societal standards, but by how she chooses to define herself. In the same way, “The Reluctant Fundamentalist” also demonstrates the frustrations that may come from one’s inability to define his or her own identity in the world; rather, society and/or close-minded viewpoints define that person’s identity the way it wants to. Changez, for example, doesn’t want to be labeled as a “fundamentalist” or “radical” by any means. Instead, American media portrays him as some sort of extremist or ally of the terrorists simply because he actively chose to abandon Western ideals and live his life based on Pakistani traditions (most of which are unfamiliar to people here in the United States). What I also want to focus on, however, is identity not in terms of single human beings, but of collective societies as a whole. This can be seen in our readings of “Persepolis” by Marjane Satrapi and “Jasmine and the Stars”, for example. Both readings emphasize a different identity of Iran than one that we’re used to seeing, an Iran that is incredibly beautiful and full of artistic life and vibrant culture, only to be subjected to common stereotypes about Islamic fundamentalism and, most notably, the requirement of the veil. Both “Persepolis” and “Jasmine” show that while yes, Iran does face many obstacles and issues – ones that plague many different nations all over the world – it’s also the homeland of these two authors, and that in and of itself shows that it’s a cherished land, one that holds special meaning for many. In the same way that you and I have many dimensions to our full identity – whether it be our race, age, gender, sexual orientation, economic status, nationality, or our dreams and aspirations – other types of entities have different dimensions to their identities as well. Iran has its good and its bad, the United States has its good and its bad, and Christianity and Islam have their goods and bads, just as each person as his or her own.

The next “big theme” that I’d like to address is the power of religion, which further branches out into smaller, more specific themes such as religion as art, religious pluralism, and the intersection between science and religion. From the very beginning (when we read “An Egyptian Childhood”), our class discussed the power of religion as both a visual and aural art form; I know for me, at least, the idea of the Qur’an being seen as art was something that was quite foreign, especially since I grew up memorizing Bible verses at Sunday school almost aimlessly. I learned, however, that the acts of transcribing Quranic verses and drawing them as art, or even just memorizing verses from the Qur’an played the role of allowing the individual to transcend to another part of spirituality. It made the Qur’an – and any other holy book that you choose to follow – something more than just a book or a set of parables and instructions; it became ingrained in you, a part of your blood and soul. What we also discussed was the theme of religion pluralism, which we saw in works such as “Children of the Alley”. Mahfouz’s “Children of the Alley”, in my opinion, was really meant to show readers that conflict between world religions, specifically the three dominant world religions – Christianity, Islam, and Judaism – needn’t be necessary because when looking at the big picture, all of these religions stem from the same origin. The tales told in each one, for example, are also told in the other, and many of the leaders of each religion – individuals and prophets who played huge roles in spreading the word of God – are existent in all three. This is all centered around a broader message of peace, the idea that if we were all to come together and notice the similarities between us, the many conflicts and confrontations that we experience day by day as a result of our differences would just fade away. That last point ties into another more specific theme of religion that we discussed in this class – the intersection between science and religion, or faith and reason. We saw this in “Ambiguous Adventure,” for example, and what we took away from it from our class discussion was similar to what I just said above: although religion and science face many differences, and thus many criticisms from opposing sides, we must be able to look at the bigger picture and see that the two are both meant to explain our lives here on Earth, and may actually correspond with each other a lot more fittingly than what we had originally perceived. All of these themes and readings, I feel, can be tied together to form a single message, and it is this message that should be considered as our class’s “takeaway,” if you will. It is a message of tolerance and of love – a reminder, as we complete our first semester here at Harvard and simultaneously begin the rest of our journey here as a blossoming young adult and a college undergrad, to never stop loving and never let go of the drive to do good and serve the world in peace and compassion. I’m truly grateful for the experience I’ve received through this seminar and for the amazing stories that I got to share alongside my classmates.