Introductory Essay

May 9th, 2014 by mbprasad

While taking this course, I thought critically about the ways in which Islam and identity are interwoven into a complex tapestry of location and culture. Overall, my blog posts explore issues of identity and the complex struggle within Islam and all religions of finding identity and defining our identity. I worked with five different mediums: painting, poetry, photography, film, and letters. My examination of identity is strongly tied to the cultural studies approach and the fact that it is hard to assert what something is when we have a broad definition of the category. For example, it is hard to say what Muslims think because it is such a diverse group. What Muslims are we talking about? Whose Islam are we referring too? Instead it might be easier to tell you more about general beliefs held Twelver Shii for example.

Many people have an ignorant view of Islam, especially given the events of 9/11 and the War on Terror. Growing up in Oklahoma, I was exposed to the ignorance and misconceptions that people had about other religions. When I say “other” religions, I mean any religion outside of Christianity. It wasn’t that the people I was around were hateful; it was just that they had never been exposed to other cultures. When you live in a very homogenous society, it is easy to have a world-view centered on the way of life that you know and it is easy to believe that you are right when everyone else around you believes the same thing. I always thought that it was so important to push past the majority opinion and learn about what else was out there.

I celebrated Ramadan with one of my friends, and I traveled to the local mosque. In hindsight I see what a limited view I had of such a complex religion. This realization is what prompted me to write the blog posts that I did. This class helped me understand the many facets of Islam and the impossibility of stereotyping the religion down to a few statements. If you asked me what defines a Muslim before I took this class, I would have told you that every Muslim follows the 5 Pillars of Islam. Now I would tell you that I have no real answer. A Muslim can be someone who emphasizes the importance of the Prophet’s family or someone who desecrates legacies of the Prophet’s family. Both would likely assert that they are following the true form of Islam. I wanted to explore the complexity of Muslim identity and identity in general in my blog posts.

In my first blog post I did this by examining the idea of what it means to be an infidel. I wrote a poem about the dangers of declaring that someone is an infidel because they don’t believe the same thing as you. If we do that, then in the end we will all be worse off than we would be by cooperating. I was not only inspired by Professor Asani’s reading, but also by the statement by Martin Niemoller.

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out– Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out– Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out– Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me–and there was no one left to speak for me.

This statement epitomizes why it is dangerous to tell ourselves that we are different than other people and why we should strive to understand them. This is incredibly relevant to the class because if we saw that one version of Islam is the true Islam, then how can we understand the complexity of Islam? This creates a complicated discussion of how people can balance having faith and still being accepting of other beliefs. Of course every believer will think that his or her ideas are correct—that is the reason that religion and faith exist. People feel that their ideas are correct, which is why they believe in them. However, it is possible to believe and to still accept others’ beliefs as equally valid. This is where the cultural studies approach is so significant. Take for example the conflict between Iraq and Iran. Much of the conflict was rooted in differences between the beliefs of Sunni Muslims and Shii Muslims. If instead we all attempted to take a cultural studies approach of it, we would likely see less conflict and more tolerance.

This is probably an overly optimistic view of the world, but this class has helped me believe that it is necessary. As my poem, “The Garden,” notes, lack of tolerance will only lead to our destruction. Even if this destruction is not a war or invasion, it will manifest in less than optimal outcomes and wasted emotions and resources. I can sit here all day and think about how other people’s beliefs are those of infidels, or I can engage in discussions with those individuals. Believing that I am inherently better or that what they believe is wrong won’t benefit me in any way. Meeting and engaging with people who are different than me will hopefully shape my own identity and allow me to grow and become more knowledgeable.

In the second blog, I looked at the Al Ghazali reading on the rules of religion and asked people about their faith for a short documentary and the value that they see in rules. I asked people of multiple faiths because I wanted to explore the overlap between religions. For me, this was really an attempt to explore how our identities are shaped so greatly by religion or our beliefs on whether or not religion is a real thing. Rules are an interesting part about religion because if we say that there are specific rules everyone must follow, then we are fail to allow a dynamic view of religion that incorporates a cultural studies approach. In my film, Mohit said that they don’t mind if there are rules as long as no one imposes the rules on him. I thought this was interesting because if rules are not imposed, then are they really rules? This goes into a discussion on how choices versus freedom affect one’s identity, which I discuss more fully in my blog about the hijab.

My third blog post focused on the readings of Islamic art and architecture. I traveled to Israel and Palestine during Spring Break and had the chance to see numerous examples of what may or may not be considered Islamic architecture like the Dome of the Rock. Set amidst the complex geo-political environment of Israel and Palestine, the identity of the architecture is even more relevant. I chose to create a series of photographs that show the Dome of the Rock in different filters. This was an attempt to see how creating physical differences in the same building The readings on art and architecture talked about incorporating politics into our interpretations of art (Necipoglu) versus incorporating ideology into a discussion (Nasr). Depending on which view we choose changes how we view the identity of art and architecture—namely its identity as Islamic or not.

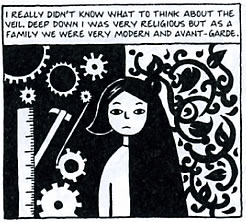

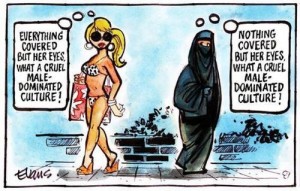

For my fourth blog post, I once again used the medium of photography and responded to Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi. Persepolis is about the Iranian Revolution, a subject about which I am fascinated. I have studied the Iranian Revolution in history classes, so looking at it from a religious-studies course was a fascinating new direction. In my response to Satrapi’s book, I chose to mirror the image that she has of herself with one side representing her religious side and the other representing her modern side. As I said in my blog post, Satrapi presents an interesting image of the hijab. She discusses the hijab as something that is very traditional and conservative, which I disagree with. However, this made me think critically about how the hijab can be a tool to assert political control over individuals. The discussion of the hijab is a critical component of the discussion on female identity in Islam. Many people argue that the hijab is repressive and forced on women. They then use the hijab as evidence that Islam is a religion against women. I think this is where events like the Iranian Revolution come into play. The Iranian Revolution forced the hijab on many women against their will. Satrapi was forced to wear the veil because society forced her. Because she didn’t make this choice on her own, she didn’t have the chance to think about what wearing the veil means. The factor of choice completed changed how Satrapi

My photograph attempted to recreate Satrapi’s image in the book but with a real image rather than a drawn image. If you look at my picture and I tell you that I was forced to wear a veil, how would it change the way that you see me? I am smiling in the photo slightly, so I wonder if it gives the impression that I chose to wear the veil. Let’s say that I instead had chosen to frown in the photo. How would that alter your impression of the hijab? How would it alter your perception of me? As I said in the blog, I am still the same person in both photos, but maybe this is because I wore the hijab for a photo and not because I was forced to.

I hope that this blog post conveys the complexities of the hijab and why we cannot make general assumptions about whether the hijab is repressive or liberating. It depends on so many factors like location, choice, and the geo-political climate. As we saw in class from the videos, women’s views on the hijab differ dramatically and completely depend on the context. Some women said it was liberating while others said that it was a configuration of men to repress women. The Mipsterz videos we watch also portray the hijab in a different light, which we have to consider in our interpretation.

In my fifth blog, I painted a canvas to show the struggle of identity that is presented in The Reluctant Fundamentalist. My canvas combines the flags of the United States and Pakistan over a silhouette of a contemplative man. This man is supposed to represent the narrator Changez who struggles with his identity as a Pakistani living in the US. I didn’t want to offend anyone by combining two flags, but flags are the best symbols of a country’s identity. Changez has a complete change in his identity because of 9/11. Both American and Pakistan shape Changez’s identity even if he is anti-American in a sense by the end of the story. The discrimination that Changez faced also stemmed from a lack of understanding about Islam or the Middle East. If people had a cultural studies approach, then Changez might not have felt like an outsider in America or subconsciously felt like he had to hide parts of his identity.

I continued the theme of how someone can struggle with identity in a post-9/11 world with my sixth blog. I decided to do the option where I chose a concept from the class and explained it in a creative way. I chose the cultural studies approach, despite that fact that it seemed like an obvious choice. As I have noted in all of my blogs, I think that a cultural studies approach allows us to be more tolerant and understanding of religions because we understand that there is not just one definition of religion. I wrote a letter to a former classmate of mine and implored him to consider the cultural studies approach because it would enlighten him on the dangers of calling someone a terrorist due to physical characteristics or labels. The experience of being called a terrorist at such a young age made me more aware of why it is so important to attempt to understand people’s beliefs before judging them or assuming anything about them.

My blogs attempted to creatively portray the fact that we cannot assume or judge others. Islam is a complex religion and is shaped my cultural and political factors that make it different anywhere you go. While a belief in Allah holds across all Muslims, most other beliefs vary. In order to build unity and relationships among not only Muslims but also all people, we have to understand how the religion, like any religion, varies from person to person because of their complex and unique identity. The importance of this ties into international relations, economic welfare, and overall happiness and well-being. This is what I really took away from the class and I hope that the same message comes out through my blogs.