The fate of fanaticism

Jan 14th, 2008 by MESH

From Walter Laqueur

|

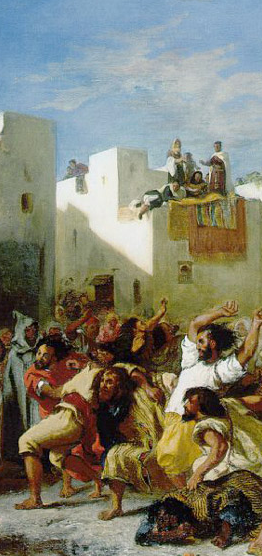

| Detail from Eugène Delacroix, The Fanatics of Tangier, 1837-38. |

It is not “the West against the rest.” Throughout human history, civilizations have coexisted and competed, and there is no good reason to assume that this will change in the foreseeable future. True, there is still considerable resistance to accepting such obvious facts as, for instance, the shrinking importance of Europe—demographically, economically, politically—even though the rise and decline of civilizations is a phenomenon as old as the hills. The position of America in the world without a strong Europe will certainly be weakened.

But looking ahead, the present threat is not really a “clash of civilizations,” but fanaticism and aggression, which are of particular importance in an age of weapons of mass destruction. There is no need to spell out where fanaticism is most rampant and dangerous at the present time. But it is less clear how durable fanaticism is, how long its intensity will last.

History seems to show that it is largely (albeit not entirely) a generational phenomenon. It seldom lasts longer than two or three generations, if that. How little time passed from the desert austerity of early Islam to the luxury of the Abbasid court in Baghdad! The impetus which led to the the Crusades petered out in several decades. More recently, in the age of secular religions such as Communism, fanaticism (even enthusiasm) evaporated even more quickly. The pulse of history is quickening in our time, everywhere on the globe.

All of which leads to the question: what undermines and weakens fanaticism, aggression and expansion—and what follows it? (In some respects this resembles the debate prompted by Leon Festinger a few decades ago: what follows if and when prophecy fails?) The importance of economic factors in this context has been exaggerated (with certain exceptions); the impact of culture (in the widest sense) has been underrated.

It is a phenomenon that can perhaps best be observed among the Muslim communities in Europe. On one hand, there has been palpable radicalization with the emergence of a new underclass, the failure in the educational process, the sense of discrimination, the search for identity and pride. There seems to have been the emergence of what was called in nineteenth-century France les classes dangereuses. But even in these social strata, it is becoming more difficult to keep the fold in line. As a leading Berlin imam put it, the road to the (fundamentalist) mosque is long, the temptations are many and “we are likely to lose about half of the young on the way.” It is a process which virtually all religions have experienced, and Islam seems to be no exception. The importance of the street gang (as yet insufficiently studied) could be as great as that of religion or ideology.

There is the contempt for Western decadence as expressed for instance in the growth of pornography denounced by Muslim preachers. Pornography has a very long history. It is a term often used loosely and arbitrarily; views and attitudes have radically changed in time and not only in Western culture. Kleist’s Marquise of ‘O, a novella published two hundred years ago, was dismissed as pornography at the time. Today it is deemed a jewel of world literature and no one would consider it particularly erotic. For centuries, there has been an erotic strain in Islamic literature, and greater experts than I have written about it. Salafis now regard it as pornography, which is haram because it is fahsha (obscenity, abomination, fornication) as stated in the Quran.

But the preachers seem not to have been too successful. The list of the countries with the most frequent surfers on the Internet looking for “sex” is headed by Pakistan, followed by India, Egypt, Turkey, Algeria, Morocco, Indonesia and even Iran. As Oscar Wilde sagely noted, he could resist anything but temptation—or as the New Testament puts it, the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak.

In brief, there is a tremendous difference between the holy writs and their exegesis and the reality in matters sexual. And this is true for many aspects of modern mass culture. After the Iron Curtain had come down and the cold war had ended, some astute Soviet observers noted that the Beatles had played a role in the breakdown of the Soviet empire. I’m in Love and Good Day, Sunshine probably did not play a decisive political role in the fall of the Soviet Union, but they were part of an underground culture which spread and contributed to the gradual subversion of the official secular religion to which everyone paid lip service.

Sexual issues and mass culture have been mentioned as a mere examples; many other factors contribute to the dissolution and breakdown of fanaticism. The point is that the fanatical impulse does not last forever, and it may peter out more quickly than we tend to think today.

But this should not lead to a feeling of great relief—the assumption that the danger has passed and that all we have to do is to sit patiently and wait. It could still be a process of a few generations, and the question arises whether that much time is left to humankind to avert a disaster (or disasters). For the first time in history, small groups of people will have the potential to cause millions of deaths and unimaginable damage; no great armies will be needed for this purpose. It is a race against time.

Comments are limited to MESH members.

2 Responses to “The fate of fanaticism”

Posts+Comments

Posts+Comments Posts+Comments

Posts+Comments Posts+Comments

Posts+Comments Posts+Comments

Posts+Comments

As always Walter Laqueur brings a long-term wisdom—a commodity in rare supply today—to current issues. Let it be noted that Walter originated the idea and practice of contemporary history which was the forerunner of the methodology and mindset of research centers today.

There are several important points worth underlining in his post:

1. Competition between ideologies and worldviews is a constant fact of history. The current one is less a clash between civilizations than a struggle against extremism that seeks to expand itself. It is roughly comparable with the previous rounds with Communism and fascism. Both of those phenomenon drew on the host country’s “civilization” (Russia; Germany, Italy, Hungary) but were not pure products of it.

Obviously, Islamist radicalism is closer to the root of the places where it flourishes, but the sum total of its history is far more than just Islam and certainly than this particular version of Islam. Indeed, the current struggle also draws heavily on combating its immediate rival, Arab nationalism, which is also a product of the local civilization.

These ideas and struggles are long-term but not permanent phenomena. They arise in considerable part due to the failure of other ideas and systems but when they fail themselves—or do not win quick success—they bring forward new ideas and competing movements. Public opinion in Iran is a good indicator of how Islamist rule breeds rejection of that system.

2. On the Western side can basically be found Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and much of Asia, too, so that “Western civilization” has been transmuted into modernism which transcends its original geographic region.

3. Walter is very correct in pointing out that the factor of assimilation or cultural influence has been widely underestimated in the West (though not among the Islamists themselves).

Despite the undermining of assimilationism and acculturation due to misguided multiculturalism (pluralism is the proper approach but that is the subject for a different essay), they remain powerful. Won’t the majority of Muslim immigrants become largely like their neighbors eventually, though it might take until the third generation? How much are the Muslim-majority societies changing despite the Islamists’ efforts?

The Islamists feel themselves on the defensive and might well be fighting a rearguard action, as was true of reactionary forces in Europe. That does not mean, though that they cannot inflict tremendous damage as European history shows. Incidentally, it should never be forgotten that Islamist forces are pretty much everywhere—except in Iran, Sudan, the Gaza Strip, and Malaysia—the opposition. In the Arabic-speaking world, Arab nationalism still governs in most places. Islamism may be a rising tide but it is far from hegemonic and has a long way to go to achieve such a victory.

4. Finally, Walter is also the parent of terrorism studies and correctly notes the tremendous danger that this strategy’s leverage brings during the interim period.

This is an important contribution that points the way for several new and different perspectives on our era’s most important, and misunderstood, issues.

Walter Laqueur’s contribution is synoptic in its learning and illuminating in showing us, incisively, the big picture. But in pointing out that there’s also a small picture, his analysis, while in many ways reassuring, is ultimately troubling.

The big picture Walter offers is that the problem we face in the Muslim world is one of fanaticism more than it is one of ideology or religion, and that the current episode of Muslim fanaticism, which threatens the world with terror, will eventually recede, much as other world-threatening episodes of fanaticism have receded in history.

The small picture Walter offers is that such recessions tend to take generations. And this is troubling because, as he points out, horrendous damage can be wreaked in so short a span of time.

Walter is quite specific. “For the first time in history,” he points out, “small groups of people will have the potential to cause millions of deaths and unimaginable damage.” In saying this he’s reminding us, of course, that Islamist terrorist groups could use weapons of mass destruction against their targets—and that they could do that very soon, well before Islamism recedes as a fanatic force.

And there are numerous ways in which they could do that. They could produce chemical weapons themselves. They could probably also produce biological weapons themselves, or get them from state sponsors or other sources. And, from one source or another, and in one way or another, nuclear materials that could cause mass casualties may well become available to them. These could be obtained as “loose nukes” (or, more likely, loose fissile materials) they might be able to buy from purloined, poorly-controlled Russian stockpiles; finished nuclear weapons they might be able to get from sympathetic or criminal sources in a destabilized Pakistan; or nuclear materials they might be able to get from still other sources, such as North Korea or, in a few years, Iran. They could also obtain, through illicit sources, fissile materials used in research and power reactors. Al Qaeda has long expressed an interest in obtaining such materials and in using them—and it, or another Islamist group, may well do so long before Islamist fanaticism recedes.

So is there is a silver lining in Walter’s analysis? There isn’t, but there is a wise warning. Walter makes clear that the targets of today’s most dangerous fanaticism can’t just “sit patiently and wait.” He’s a fine historian but also a fine analyst of the current moment. And the current moment, with its possibilities of mass casualties, requires that we defend ourselves, even as we recognize that the world isn’t necessarily fated to contend with Islamist fanaticism forever.

In the West we’ve only begun to do so; we’ve made damaging mistakes, we’ve left open large holes of vulnerability, and we have yet to learn how to balance civil liberties against actions we take in our “war on terror.” But we seem to be finding our way. No doubt, as time passes following 9/11, the tendency to grow lax will increase. Alas, it may take another 9/11—or multiple attacks that are smaller, or one or more attacks that are bigger—to mobilize us in this multigenerational, and potentially very lethal, struggle.