Reflections

ø

This semester has been a long and incredibly enriching experience for me. I originally signed up for this class, I intended to fulfill a general education requirement that also happened to fall in my concentration. Within a few days, though, I realized that I was enjoying the course because of the course’s unique approach to the material. Most classes approach material through lectures and readings of facts and dates, leaving the student with only a two-dimensional understanding of Islam. However, in this course we covered facts while also engaging material in tangible ways that left me with a fuller understanding of the nuances of the many different communities of interpretation in Islam. In fact, I learned more about Iranian culture from just a brief unit in this course about Islamic forms that originated in Iran than I did from an entire semester in a class purportedly about Iranian culture and society.

I have not engaged with material in such a hands-on way since my senior year of high school, when in an effort to experience another culture I decided to observe Ramadan. Rather than just read about it and learn the associated rules, I found myself in the midst of a transformative experience where I learned more from having to consider many little things than from the actual discipline itself. I had thought originally that it involved simply not eating, but the entire mental experience is completely different; I was always thinking about food and how hungry I was, how to avoid feeling isolated from my peers, and realizing the incredible amount of discipline it took. I learned from that experience that being a Muslim in a majority non-Muslim country is can be a challenging experience. I found that fasting at mealtimes with my classmates often drew questions in an accusatory tone from some of my peers like “You’re a Muslim?” and ended up choosing to isolate myself to avoid some of the biases. One of the reasons for Ramadan is to remind one’s self what it is like to be poor and unable to eat through experiencing the same hunger. Reading that sentence and feeling the hunger itself are two very different experiences. Reconciling and respecting the different cultural contexts in which Islam is manifest while trying to experience aspects of it myself has since become a key lens through which I approach Islam.

Over the course of this semester, much of my work has been inspired by the many different cultural contexts that have been influenced by Islam. My experience with Ramadan showed me that people respond to Islam differently in many different cultural contexts. From what I could tell on other students’ blogs, this was a common thought. I was especially moved by Margot’s hijab and Shaomin’s commitment to spending a week wearing various forms of hijab. It seemed like the three of us responded in a similar way, namely, that many Muslims in the West are “othered” because of inherent bias, and this is a critically shapes the Muslim experience, but also that we would not have gained those critical insights without having put ourselves in the shoes of a Muslim.

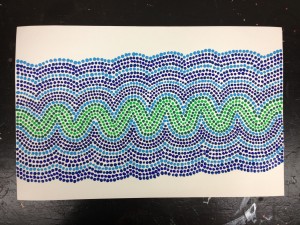

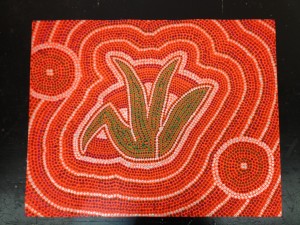

My art this semester was influenced both by ability and by this theme of intercultural understanding of Islam. My first piece of the semester was an Aboriginal Australian dot painting representing the calligraphy for the word “Allah.” The project arose out of the fact that dot painting is the only style of painting that I feel I can produce beautiful work in, and because it was a way to think about how Islam might be interpreted had it expanded that far into Oceania. A critical theme this year was the way in which Islam spread across the world and in every locale adopted unique characteristics from that area and created a unique regional culture. While Islam never spread to Australia, it is likely that dot painting might have been adopted both because of the Aboriginal aversion to depiction of humans but also because of the art form’s uniqueness.

The piece was interesting to my friends, whose responses were divided along religious lines. Those who were Muslim, in the class, or could read the Arabic and Persian script immediately saw “Allah” in the context of a piece about life, while those who were not familiar with it saw a stylized paper crane. It was especially interesting because both groups came from completely opposite ends, but still saw the same representations in it despite interpreting the symbols through their own unique cultural lens. I did not intend for the artwork to have this effect, but it was a strong reminder of how universal artwork and certain ideas can be—a piece need not be defined as “Islamic,” “Christian,” “Western,” “Dutch” or anything else specific to appeal to a person’s sense of beauty and humanity.

My first creative piece was perhaps the most disconnected from the rest. I was surprised that it ended up as my only piece of written work because of my love for creative writing and poetry, and is my only piece that I didn’t approach thinking about this issue of intercultural interface. Despite that, it ended up, like my other pieces, being a piece with an air of universality. Just as Rumi’s poems are revered across the West for being love poems, while in much of the Muslim world they are seen as devotional, this poem, while nowhere near the caliber of Rumi’s work, can be seen through both lenses.

While my second piece can be seen as part of the progression of understanding Islam through multiple lenses, the inspiration was actually drawn more from the sense of misunderstanding than understanding. One of the biggest problems today is that people have an idea of Islam as a single cultural monolith; they see a representation of a religion instead of individual human beings. The piece serves as a commentary on the ways in which institutions like organizations of religion (such as the Saudi or Iranian government or a manipulative press) can interfere with understanding of the religion and its nuances. In that sense, the piece is a counterbalance to the other pieces by stating why we don’t necessarily see more efforts at cross-cultural understanding.

My third and fourth pieces are in a sense the crown jewels of my collection. I knew immediately when I considered taking this class that I wanted to see if I could somehow incorporate my skating and my choreography into my responses, and when I had the chance after spring break, I spent a morning in the rink experimenting and playing around with music and the choreography. I would put the music on, reflect on the themes of the two readings I was trying to engage, then see how the ideas translated to movement. While initially as I began choreographing I thought to myself that these pieces were going to be so obtusely linked that it could be laughable, I found that the two lenses of the West and of Islam both merged to form a piece of choreography that has deep roots in both Western choreographic tradition and Islamic inspiration.

The pieces were interesting because on their own, people saw them as interesting and moving, even without knowing the motivations behind the choreography. Just as in the real world of skating, often one won’t understand what is behind the choreography unless one sees an interview with a skater or hears it mentioned by television commentators. This was a continuation of this idea of pieces that can be seen from two different perspectives. Because the pieces were both performed to decidedly Christian pieces of music – one is based on a Russian Orthodox legend and the other is a funeral march – they also engage to a certain extent with the idea of interpreting some of the traditions through the lens of a different culture, this being a Christian or figure skating lens. More than any other pieces I did this semester, I feel as though these two, especially my taziyeh piece, ended up requiring the least amount of explication of anything I created this semester.

Following the skating pieces I stepped back from creative reading responses and moved on to the mosque design project. I was especially proud to have come up with most of our mosque’s concept and design after our group agreed that it would be an interesting and unique challenge to build it in my home state of Alaska. This project was an especially interesting example of trying to meld together different traditions and locations, both between the US and Islam but also between a unique community of Muslims from many different backgrounds. It was a challenge to find a way to nod to the communities’ origins while still remaining respectful, and we were proud to also come up with a building that can be seen by Muslims as a safe space for prayer and contemplation, but also by non-Muslims as non-offensive, beautiful, and belonging in the landscape.

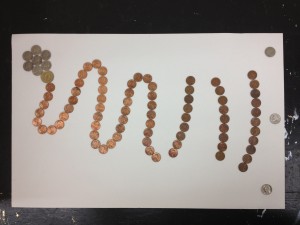

I came up with the concept for my fifth creative project early on in the semester, but it wasn’t until I sat down in the Pfoho Art Room with all of my books that I came up with the concept of using the pennies and their level of tarnish to represent the physical and emotional journey of Michael Muhammad Knight both across the United States and through his beliefs in Islam. The piece is one of my more literal interpretations of showing the intersection of different cultures because of the use of American money to create the design, but I also intended for it to represent the different directions from which one approaches God. In the piece, the path followed spells out Allah, but as I represented it, the path goes from left to right instead of from right to left. This piece, too, is one that would be approached differently by different people because of these two directions and because some might believe that the tarnish level of the pennies represents something other than his beliefs. As with any art, it is open to interpretation, and I am curious to hear from others what this piece says to them. The initial response from my peers has found it cryptic until they have read the explanation.

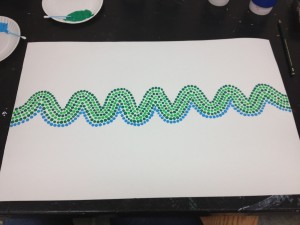

My final piece was, to some degree, an attempt to come full circle on the class. I had known all semester that I wanted to do another dot painting, but it wasn’t until the last week of class that the concept finally came to me. I thought of interpreting The Conference of the Birds without using birds, but instead using a path 30 dots wide that dips seven times over its length to represent the birds and the valleys of the story. As the most abstract of my interpretations, I doubt that most anyone from any context will recognize the inspiration, but they will be able to see the theme of a path that I also applied to my taziyeh skating piece and my coin piece. It also continues the intercultural theme that I began with the first dot painting, showing a Persian poem through the interpretation of an Australian. Like the coin piece, I am curious to hear what the general response to this piece is. While it is less ambitious than my calligraphy project in terms of size and scope, I still was very proud of the concept and the overall look; it is a piece that, while representing something Islamic, can be seen by anyone as beautiful.

This class has been an enormous journey for me. I created more visual art for this class than I have created since the seventh grade, and it has pushed me to think about putting meaning into every detail. In the dot painting, the meaning literally went down to every single point on the page. Never before had I so engaged with the human side of Islam, the side that shapes the identity and lives of Muslims more than any other force. From music to recitation to poetry, the variety of ways that Muslims engage with their religions, their identities, and each other is truly amazing.

It is my hope for the future that more people will choose to approach Islam from this side. As we experienced at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the experience of seeing the art and seeing the diversity of practice and belief across the Muslim world can truly change the thought processes of many who have misunderstood or misappropriated Islam. One rarely approaches the dominant American culture by studying sentences like “on Sundays, Christians go to Church.” People learn about these things by listening to music, by visiting churches and museums, and by interacting with other people. In the same vein, it would bode well for the world to understand who makes up the community of Muslims, and not what defines Islam as a religion.