Prologue

May 8th, 2014

Prologue

“Lā ʾilāha ʾil ʾāllāh, muḥammadun rasūlu-llāh” – There is no God but God, and Muhammad is his messenger. The familiar Muslim profession of faith, the shahada, is one of the central tenants of Islam, and its recitation in public one of the five pillars of Islam. It is a profession of Unity, both in the sense of the explicit assertion of the unity of God, and in the sense of the unity of Muslims in this fundamental belief. Yet one of the most striking aspects of the Islamic tradition today is the remarkable diversity of practices associated with it. Islam cannot be reduced to the often-cited five pillars of Islam, nor is it entirely captured in the sacred script of the Qur’an. Islam is a religion practiced by Muslims, literally “those who submit to the will of God, or Allah. But with the myriad of choices faced by believers every day, the issue of discovering God’s will becomes far more complex. One might turn to the Qur’an for guidance, and indeed, this is often the first course of action for many Muslims. But how can such a compact book, comprising of 114 relatively short surahs (chapters), hope to explicitly describe the appropriate behavior for the uncountable set of situations life presents? To address life’s more subtle concerns one may turn to personal intellect, to tradition, or even to external sources of wisdom. Regardless, each believer must inform his lifestyle, and by extension his religious practice by his individual circumstances. In short, there is no unified religion of Islam. Islam may be a monotheistic religion, but it is certainly not a monolith.

The diversity within Islam runs so deep that it even affects the expression of an explicit command from the Qur’an: to revere the prophet of God, Muhammad. An almost universal, ever-present element in the life of Muslims, the “seal of the prophets,” Muhammad, finds his way into the hearts of his followers in various ways. For example, many Muslims connect to the prophet by imitating his recorded behavior and practices, which are collectively known as Sunnah. Others, like many of the Sindhi people, express their connection by writing poetry with the prophet as a subject or theme (Asani, 159). However one of the most striking differences is the appreciation of the fundamental ontological nature of the figure of the prophet Muhammad. In some circles, the prophet Muhammad’s role is strictly limited to that of the human receptacle for the revelation of the Qur’an. As such, he is deserving of great respect, but not to be elevated to any higher station. To others, the prophet takes on another metaphysical dimension as the ideal man: man’s perfect state and his origin in the sense that a platonic ideal is a source. This second view is captured by the piece on the so-called “Primordial Muhammad” from which the rest of humanity was derived. In this piece, one sees the name, Muhammad, in the center of a circle, and touching one of the encircling dots. This is meant to represent that Muhammad is the origin of humanity, not in the sense of its beginning, but rather in the sense that a circle’s center comprises its origin. Further, Muhammad has a dual expressed nature as “seal of the prophets” and thus, in the circle of time, dotted by the various prophets, he holds a distinguished position, indicated by the light emitted from his dot. And of course, there are even more debates about the appreciation of the prophet Muhammad in Islam. The one most relevant to this blog is the divide over a particular hadith (saying of the prophet) that is frequently cited to justify the ban on images of the prophet and other beings, in which some see this ban as a means of showing respect, while others see their images as a means of expressing their love for him.

This ban on images would seem to pose a daunting barrier to the progression of Islamic art, and in fact there are many other challenges to the aesthetic dimension of Islam, not the least of which is the debate over the place of music and Qur’anic recitation. Still, one cannot help but be amazed at the staggering quantity and quality of work produced by the Islamic community. But, can one be sure that all of the art is truly “Islamic” in nature? It seems a little presumptuous to claim that all art created by Muslims is “Islamic” in nature. In fact, scholars are still split on the definition of Islamic art, or whether it truly should be a category of art at all. However, one notable scholar, Professor Seyyed Hossein Nasr, does believe in the deep unity and profundity of Islamic art. He expresses his view in his book Islamic Art and Spirituality, saying, “Whether in the great courtyard of the Delhi Mosque of the Qarawiyyin in Fez, one feels oneself within the same artistic and spiritual universe despite all the local variations in material, structural techniques, and the like”(Nasr, 3). Inherent in this view is the belief that Islamic art cannot be reduced to a set of materials or their means of construction; there is something symbolic or hidden in Islamic art that transcends its physical manifestation. It is not something that one can decompose entirely, but something that one must “feel.” In fact, according to Nasr, Islamic art is not concerned with the “outward appearance of things, but with their inner reality”(Nasr, 8). Thus, to Nasr, at least, Islamic art is highly symbolic, where every detail may be a reminder of nature’s inner reality, the innermost of which is God. This maximalist approach to Islamic art is explored in the crude piece presented in the post on the “Seven Spheres of Heaven.” In this post, a multitude of meaning is drawn from a relatively simple clay tablet to show how every minute detail of this piece of art could be viewed as symbolic of the Mi’raj, Muhammad’s ascent through the levels of heaven to meet God. Such an interpretation requires a bit more that the explicit expression of the artwork. To extend this principle, as Nasr would put it, “It is therefore to the inner dimension of Islam, to the batin…that one must turn for the origin of Islamic art”(Nasr, 5). And thus, art is the necessary companion of those who thirst after any inner meaning, or batin, in Islam.

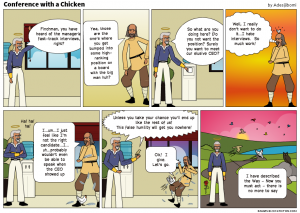

The prime example of a Muslim concerned with Islam’s hidden dimensions is one who follows the branch of Islam called Sufism. Sufism is a term that is quite difficult to define, however, broadly speaking, Sufis are those who believe in a God that is more immanent than the more distant deity of less esoteric interpretations of Islam. Central to the belief is the view that, since the appearance of creation in “pre-eternity” on the day of alast, all of reality has been bent towards a return to union with God. To the Sufis, this is accomplished by an arduous process of cleansing of the self, and a humbling of the ego, or nefs. A particularly meaningful ayat (verse of the Qur’an) to Sufi’s is “To God belongs the East and the West; wherever you turn, you will perceive the face of God.” (2:115). From this, many argue that all things in nature have a symbolism and a hidden lesson to be learned about the true nature of God. In fact, the overwhelming desire for knowledge of and union with God is the source of the multitude of Sufi pieces of art, nearly all of which are laden with layers of symbolism and references to nature. One of the great Sufi poets, Farid al-Din Attar, is best known for his epic poem, Mantiq al-tayr, or “the Conference of the Birds.” In it the poet beautifully describes the souls path to union with God symbolized by the story of a host of birds searching for their king, the Simorgh. Each of the birds in the story takes of the characteristics of a particular human personality, and is taught and led according to their character. Thus, the story provides a guide to the Sufi path for all different types of dispositions. In the post, “Conference with a Chicken,” the lessons from the stories centering about the finch are compressed and re-expressed in comic form to show that the story has not lost any relevance since its medieval creation. Like many great poems, “the Conference of the Birds” has proven to be quite timeless.

Poetry has long been a revered method of expressing devotion for Sufis, however, in a wider Islamic context, it is far more divisive. The history of poetry in Islam is one of misunderstanding and conflict. Before the official advent of Islam with the prophet Muhammad’s original recitation of the Qur’an, pre-Islamic Arabia had been home to a large number of poets whose poems were most often employed in the polytheistic faith of the region. At the conception of Islam, the prophet went to great lengths to distinguish himself from the poets of the time and establish the Divine nature of his revelation (Renard, 109). He condemned many poets and waning his believers to be mindful of them Yet as his position solidified, one of the great poets of the time and formerly one of Muhammad’s greatest opponents, Ibn Zuhayr, presented the prophet with an original composition in his honor. The positive reception of this gift has caused debate over the position of poetry in Islam, an issue that was, and is still, largely left to be answered by cultural contexts. For example, poems may be composed in honor of the prophet, like the Sindhi poems mentioned above. They may also be means of expressing a heartfelt love for God, as many Sufi poets, like Attar, were wont to do. The post on “Divine Love” explores how poetry found expression in the context of Medieval Islamic Persia. The theme of love and the images used to express it are particularly compelling in these renderings, yet at surface level, they have nothing to do with the exoteric practice of Islam. Nevertheless, there are still parts of the Islamic world that shrink from poetry of any form, while other parts embrace poetry to such a degree that it is seen as having a mystical power. For example, the Egyptian poet, Al-Busiri, wrote a poem, the Burda, which is purported to have been received by the prophet in a dream and lead to the poet’s miraculous recovery from a terminal illness. Today, many still hold that the poem has special healing powers, and it is one of the most widely memorized poems in the Islamic world. Poetry does holds a tenuous position in Islam, but its potency is undeniable.

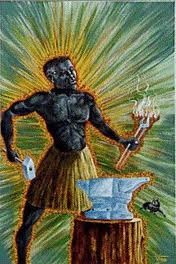

Though it is extremely popular, the reception of the Burda, and most poems vary widely across different cultures. In similar fashion to the imposition of pre-Islamic poetry on Islam, many cultural traditions survive, and find new life with the arrival of Islam. For example, the Berti people of Sudan find that there is a certain spiritual potency to drinking erasures of verses from the Qur’an and lists of the names of Allah (El-Tom 415). This practice is widely employed as a form of medication by faqis, which are better known in the traditional Islamic sense as hafiz, those who have memorized the entire Qur’an (415). This is likely the by-product of a pre-existent traditional conception of the process of spiritual healing blended with the sacred place of the Qur’an in Islam. Novel ritual practices such as this are, in fact, quite common in Islamic Africa, whether it be through devotion to certain marabouts whose practice resembles that of priests of traditional religions, or from the belief in the baraka (spiritual blessing) received from the creation and display of a certain Cheick Amadou Bamba by the Muridiyya Sufi order in Senegal. The intersection of cultural norms in Islam is discussed in the post “Ogun’s return,” in which element from a traditional Nigerian mythology (Ifá) are embedded within a traditionally Persian, Arabic, or Urdu love poem. The traditional Sufi imagery and Yoruba (Nigerian tribe) insertions serve to express the same sentiment, a desire for return to God. This piece shows that one cannot hope to understand Islam without first specifying the cultural context under which particular practices emerged.

The need for contextual understanding, of course, is not limited to the realm of cultural differences. The interpretation of Islam is just as temporal as the beings who practice it. Islam is a dynamic religion, and while it is evident that certain elements of the tradition persist throughout the ages, the words of modern day scholars cannot be equated with an ancient master such as Al-Ghazali. Oftentimes, there will even be a lack of consistency between the two time periods under investigation. Time has presented Muslims with different struggles over the ages, and the writings of the thinkers have mirrored the issues of their day. For example, in the Complaint and the Answer, Muhammad Iqbal employs the poetic form of conversation with the Divine to examine the place of Muslims in the modern world. In the Complaint, he poses as a believer who charges God with having forgotten His people and left them to their present decline (Iqbal, 3-33). Yet, in the Answer, the poet responds in the voice of God saying that His people have forgotten the ways of their forefathers (namely Ali, Uthman, Ghazali, ect.) and instead, “education and refinement” have lead them to idolatry (Iqbal 59). Iqbal employs this traditional method of expressing devotion to express his view about the state of Muslims in the wake of the expansion of the West and Modernism. Many similar figures followed suit, choosing to express their ideas by drawing on the traditions of the past, and in some cases prescribing a return to said traditions. In like fashion, the post, “Nasrudin and the Christian” employs the use of a traditional Islamic folk-tale to comment on the ideas of some of the reformist thinkers. The simple stories of this character, Nasrudin, are typically used to present compact truths or bits of wisdom, and so they provided an ideal means for a concise critique of some reformist stances. Through the story presented, one is able to perceive the power of using old mediums for modern reflections. Without a doubt, the ideas in Islam are not exactly those conceived of at its inception, but there does seem to be some continuity, which is quite evident by the efficacy derived from the past tradition.

Islam may, in fact, comprise a continuous tradition, however, the price of this dynamism is the unity of a clear definition. And yet, there remains some conception of Islam as one distinct religion. As the Sufis might say when speaking of the nature of God, Islam participates in both unity and multiplicity. It is multiple and yet one. To ignore either of these aspects would be to miss the true character of the religion. As we have seen, sect, culture, and time each play their role in contextualizing Islam. And yet, according to many scholars like Prof. Nasr, there is a distinct “universe” from which all of Islamic art springs. This, however, requires a very nuanced understanding of the batin, or inner meaning of the tradition. For those lacking the exposure necessary, it is far simpler to refine one’s understanding of the multiplicity of Islam and its artwork. One would hope this could combat sentiments of the Muslim as “the other.” If nothing else, this blog attempted to present the necessity and, indeed, beauty of context in Islam. That being said, what is presented here is but a drop in the sea of Islamic art, and only provides a fleeting glimpse at its diversity and profound beauty.

Works Cited

Asani, Ali. “In Praise of Muhammad: Sindhi and Urdu Poems.” Religions of India in Practice. Ed. Donald S. Lopez. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1995. 159-86. Print.

El-Tom, Abdullahi Osman. “Drinking the Koran: The Meaning of Koranic Verses in Berti Erasure.” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 55.4 (1985): 414. Print.

Iqbal, Muhammad. Complaint and Answer: Shikwa and Jawab-i-shikwa. Trans. A. J. Arberry. Lahore: Sh. Muhammad Ashraf, 1955. Print.

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. Islamic art and spirituality. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987. Print.

Renard, John. Seven doors to Islam spirituality and the religious life of Muslims. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. Print.

Ogun’s return. (Weeks 8/9)

May 8th, 2014

The ghazal is a form of Persian poetry, traditionally in the form of love poetry. It has become especially popular in the Persian, Arabic, and Urdu languages. Structurally, it is composed of couplets or verses, called baits. These are meant to both blend into the overall theme of the poem, and stand alone as a virtual poem in themselves. These poems are ment to have a very distinct rhyme structure. The bothlines of the poem’s first bait, and the second line of all preceding baits are to have a refrain, or radif. Before each radif, one usually finds a qafiyah or a word which rhymes with the others preceding the refrain. Finally, it is often customary for the poet to refer to themselves in the final verse of the poem, though through some pen-name, or takhalus, which reveals something of the character of the poet.

I found my inspiration in the 6th Ghazal by Hafiz in the book, Green Sea of Heaven, recreated, translated in English below:

O dawn wind, where is my love’s resting place?

Where is the moon’s house, that rogue, killer of lovers?

The night is dark, the road to the valley of safety lies ahead.

Where is the fire of Sinai? Where is the moment of meeting?

All who come into this world bear the mark of ruin.

In the tavern ask, “Where is the sober one?”

He who understands signs lives with glad tidings.

There are many subtleties. Where is an intimate of the secrets?

Every tip of our hair has a thousand ties to you.

Where are we? And where is the accuser idle?

Reason went mad. Where are those musk-scented chains?

Our heart withdrew from us from us. Where is the arch of her brow?

Wine, minstrel, and rose are all ready

but there is no pleasure in celebrating with her. Where is she?

Hafiz, don’t take offence at autumn’s wind over the field of the world.

Think rationally: where is the thornless rose?

I attempted to create an English version of a Ghazal, with the same structural elements. My refrain is also an indicator of the subject of the poem, “to return,” and before each refrain a word is rhymed with the first qafiyah, “deign.” My pen name is a reference to the Yoruba deity of Iron and warfare, who is quite fond of solitude. This is both a reference to my heritage and personality. The message of this last verse is meant as an exhortation to those with such a disposition. Finally, each couplet is designed to be a story unto itself, with a particular symbolism.

Ogun’s Return

Where is my love this day? When will he deign to return?

Where is the path to the Magi’s house? There I go, in pain, to return.

Bewildered, I am content to wait in the woods alone

Finally, I am convinced by the goddess of rain, to return.

If you should ever be driven away, and the sweet scent of your hair disappear,

The fires of my passion would burn till your palm wine lead me, insane, to return.

Last night, hanging from chain of Orisanla I lay sleeping,

Till your servant awoke his brother, to strive, to strain, to return.

Oh, Ogun, forget your exile, abandon your nature. Remember,

To examine the rosy cup of truth to see all else is vain, to return.

The traditional Persian ghazal is quite remarkable for the Sufi symbols that give it such depth and meaning. There are a few symbols that are typically employed, which have multiple layers of meaning but all center about love. They frequently appear in varied form to produce nuanced effects in the reader. However, different sufi traditions appreciate artistic expression in different ways. From the Mourides of Senegal with their images of Cheick Amadou Bamba, to the Dervishes from Konya, to the Qawwali musicof South Asia, practices arise within particular cultural contexts. Thus, to present this intertwining of culture and religion, I attempted to tie in symbols from a traditional Yoruba Mythology (Ifá), and match it with the symbols of a traditional Ghazal. A brief explanation of the various symbols and references may be found below:

- “Magi” – Jewish authority who is seen selling wine to the distraught subject of the poem.

- “wait in the woods alone…goddess of rain, to return” – this is a reference to a story where the deity Ogun (see above) hid himself in the solitude of the woods and would not return until the goddess of the seas and water, Osun, used her feminine charms to convince him to return to the other gods.

- “scent of hair” – a symbol for the beguiling beauty and charms of the beloved (which is often God)

- “palm wine” – wine is a frequent symbol in ghazals for the intoxication of love. Palm wine is the subject of many stories in Yoruba mythology. In this context, it refers to a time when Ogun was deprived of his palm wine and threw a devastating fit.

- “Last night” – this can often refer to the time of pre-creation, or “pre-eternity”

- “chain of Orisanla…his brother” – this refers to one of the creation myths of the Yoruba in which the older of two brothers was tasked with the spreading of sand (land) on the earth. But when he climbed down from heaven on a chain, he was tricked by one oth the gods into drinking too much palm wine, and promptly fell asleep. When his younger brother saw this, he came down, accomplished his brothers task for him, and founded the human race, then Orisanla awoke and followed his younger brother back to heaven.

- “your servant” –an implicit reference to the prophet Muhammad, who is ment to take the place of the younger brother in the above story as the founder of the human race (in an esoteric sense).

- “rosy cup of truth”—this is a reference to the cup of Jamshid, a mystical cup wich allowed one to see events far away. It also references roses, which is yet another symbol of love, and often the beloved to another familiar symbol, the nightingale.

Conference with a chicken (Week 10)

May 6th, 2014

The Conference of the Birds, is an epic poem by the master poet Farid ud-Din Attar in the 12th century. The rough outline of the begining of the story is that a group of birds, each of whom represents a particular human characteristic or flaw. They are all lead by the mystical Hoopoe, a bird associated with the wisdom of Solomon, in search of the legendary Simorgh, their king. Before setting off, however, each of the birds forwards an individual complaint to explain why he cannot undertake the arduous journey to find the Simorgh. The rest is such a wonderful tale, which becomes an allegory for the souls journey to find God, that I will leave the rest for the interested reader. For more, see the video animation below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5n9RgkM-sZQ

Conference with a Chicken

…Next time: “Owly Conferences”

This comic is meant to bring new life to this old classic. It puts a modern setting to the complaint of the Finch and the Hoopoe’s response. The finch is symbolic of cowardice, and, in the story, moans that he would never be capable of Simorgh, and would surely “turn to ashes” in the presence of the Simorgh. Instead, the Finch hopes to find peace without the struggle of the path. In characteristic fashion, the Hoopoe brings the hypocrisy of the finch to light, warning him that his negligence will not save him from his fate without the Simorgh.

This particular strip shows one office worker hailing his co-worker, Finchman. Like his namesake, Finchman is too tied up in his own cowardice to face the opportunity facing him. Instead, he comes up with multiple excuses to avoid such trials. In the end, his wise friend, has to jolt him into action. Many different symbols are employed in this strip to attach it to the original story.

The unnamed, wise worker is seen with a bird perched on his shoulder, has a halo hovering above his head, and has distinct white hair, and even eyes. Beyond making him a striking figure, these all associate him with the prophet Solomon, a sufi favorite, who was supposedly capable of conversing in the language of birds. In this piece, he acts the part of the Hoopoe, his alleged companion, and even quotes the last lines of the poem (in Darbandi and Davis’ translation) to provoke the sympathetic reader int action.

Finchman’s association with his counterpart primarily comes from his name and the color of his shirt, yellow. Though he does have a sort of unkempt air, that suggests a certain lack of ambition. In this strip, we see his modern-day bird counterpart emerge when he reveals his true character. This avian companion becomes more and more prominent, until we see the character giving in to the advice he was given. In the end, we see both representative birds speaking along with their counterparts, then leaving on their journey, likely to the Conference or to the Simorgh himself.

(Nasrudin and the Christian) Week 11

May 4th, 2014

Beyond their value in entertainment, stories provide wonderfully comprehensible perspectives at the most confounding aspects of human behavior. In factthey are even mentioned in the Qur’an: “So relate the Stories; Perchance they may reflect”(6: 176)(Tales of Nasrudin, Ali Jamnia, p.4). Although his stories were never related by any great sufi masters, Nasrudin and his stories have resonated throughout the world, and particularly in Turkey and throughout the Middle East (Jamnia, p.4). Mulla Nasrudin is an extremely simple character (though the title implies he was a religious scholar) who often appears in humorous situations that, through their oddity, often bring out some wisdom that is difficult to explicitly state. Nasrudin stories have become very popular among the common man. They are typically composed of a short, pithy, often humorous story, and a key to the story, composed of a moral and a little extra nugget of wisdom. As such a popular media based in an old tradition, I saw these stories as a means of expressing views on society, much like Muhammad Iqbal’s famous poems, “The Complaint” and “The Answer.” I sought to embody a personal sentiment about many of the reform movements in Islamic states. I found my inspiration in the following two stories:

Story 1 : Take Refuge in God

One of the rulers asked Mulla Nasrudin ,”At the time of the Abbasid Caliphs, it was customary for rulers to be given titles which ended with the suffix –God. For example, there were titles like ‘who was successful by God,’ of ‘trusted in God,’ or ‘took help from God.’ What title should people say when they see me?”

“The best thing to say,” expounded Mulla, is “ ‘I take refuge in God’.”

KEY

Polititians are like this. They occationally need to be reminded that their actions do in fact impact real people in real situations. Nasrudin seems to be saying that it is best that people avoid contact with officials… a wisdom that still offers much today.

It is the true mark of the tyrant that other people are not real to him: he is ‘the only game in town.’ In this case the tyrant is the lower self. When the self is challenged by the presence of God, its last trick may be for it to claim to be God. To say “I take refuge in God” is to deny the lower self this refuge. ( Jamnia, p.107)

Story 2 : A Conversation with a Christion

A Christian man was eating meat during the period of lent which was an illicit act according to his creed. Nasrudin saw what he was doing and went over to share some of the food. The Christian rebuffed him by saying, “What do you mean Mulla?” Christian meat is illicit for you Muslims!”

Nasrudin instantly replied, “I am among the Muslims as you are among Christians.”

KEY

There is an old folklore saying, “Drop a dog in rose water and it’s still a dog.” So too, a hypocrite is what he (or she) is regardless of their confessed beliefs. And how often do we find ourselves worrying about someone else’s impurity of heart so as to avoid looking at our own? On the other hand, those who understand the ‘meat’ of religion will not be separated by rite and creed, however important and necessary these may be on their own level. ( Jamnia, p.64)

In my own, I attempt to address a particular type of the “back to fundamentals” reform movement, by having Nasrudin direcly reflects the Egyptian thinker Tahtawi and his famous quote “When I was in Europe, I saw much Islam everywhere but I saw very few Muslims; now I am back in Egypt, I see many Muslims but little Islam.” It also addresses the idea of “Islam as progress,” as pioneered by Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan. Both of these thinkers took the radical stance that there was nothing in conflict between the Western thought and Islamic thought. Though I tried to bring to light a more subtle understanding of progress:

Nasrudin and the devout Christian

One day, one of Nasrudin’s friends brought him to a city saying, “This is the most devout Islamic city in all the land. All the men are bearded and have memorized the Qur’an back to front, and all the women are covered head to toe.” While they were going, Nasrudin fell asleep, as his friend had been very longwinded in his praise of the city and it’s people. When they finally arrived, they promptly woke Nasrudin, but he refused to dismount, saying, “I see all of the muslims, but where is the Islam in the city? My friend told me that our destination was the most devout Islamic city, yet I see no devout Islam, thus I must still be dreaming. Let me continue on our journey, so that I may wake up.”

When his friends saw they could not convince him, they journeyed on, hoping he would soon come to his senses. When they stopped in the western part of town, where people were less concerned with religion, Nasrudin once more awoke, and this time he said, “now I see no muslims, but more Islam. But the people are not the most devout, so I am still dreaming. Let us continue.”

Finally, while they were traveling on, they passed the poorest part of town. There, they saw an old, bent Christian clothe and feed a beggar. At this, Nasrudin immediately woke up and jumped down saying “We have arrived!” His companions said, “surely you are sleepwalking!” To which he responded, “I cannot know, but this man has woken my heart, so I trust in God that I am truly awake.”

KEY

We often forget that outward rituals and practice are no substitute for inner practice of Islam. No matter how much one resembles the prophet, or how much one heaps on “modest” clothing, the truly important is one’s inner submission. The hypocracy can be a barrier to true progress.

However, without this external practice, we can often lose our way, or never start on our path at all. It may allow for worldly progress, but internal progress may be left by the wayside. In his immediate recognition of this characteristic in this man outside of Islam, Nasrudin seems to be saying that a state of Internal well-being and its progress is more important than both external devotion and outward progress, and is the sign of true devotion.

The final exchange is more subtle. In this Nasrudin seems to be implyingthat he does not know the difference between sleeping and waking, symbols used frequently to denote life and death. But as his “heart” has been awoken, he can see with his “eye of the heart” and perceives clearly the truth of the situation, a power that is only possible through God.

While the actual historical figure of Nasrudin is still a subject of heated debate, scholars do seem to agree that a similar figure existed in 13th century Aksehir in Turkey. A celebration in honor of his life is celebrated every year near his supposed tomb: the “International Nasreddin Hodja Festival.” For more information on the historical Nasrudin, see any of the works of Professor Mikail Bayram, who has made his life’s work the uncovering of this character’s hidden past.