Final Project – Introductory Essay

ø

The Power of Religion

At the outset of the course, I must admit that I knew very little about Islam or South Asia, let alone the relationship between the two. As I have mentioned, growing up in a mainly Catholic suburb of Boston, I figured other major religions, such as Islam, operated in the exact same way: You’ve got one book, one creed, one Church, and one Pope at the head of it, with all his cardinals and other administrators to keep it all organized and uniform. Everything works out such that a Mass in Boston is just about the same as a Mass in Puerto Rico, and likewise the fundamental beliefs between both Parishes are more or less identical. However, after having taken this course, and truly growing to understand what Islam is and how culture affects it so dramatically, I now see that I could not have been more mistaken.

For my project, I chose six of the readings spanning throughout the course that piqued my interest and, in my mind, taught me the most about Islam in South Asia. These readings can be broken down into a few main categories: The influence of culture on Islam and religion in general, in particular the integration of certain aspects of Indic culture to the Turko-Persian Islamic culture and vice versa; organization of Islam within the Muslim community, including different reform movements and disagreements on how the religion should be practiced; and finally, the increasing politicization of religion in today’s world and the use of religion as a political tool and identity marker, especially in the case of Islam and Hinduism in today’s South Asia.

To begin, I was fascinated to learn how Persian and Hindu culture – which I assumed to be two completely different worlds – were actually very similar and in fact had profound effects upon one another historically. I first looked at “The Two-and-a-Half-Day Mosque” by Michael Meister, in which Meister goes into detail about some of the first South Asian mosques built by Hindu workers just as Muslims rose to power in present-day India. The thing that marveled me the most was how flawlessly some of the techniques and artistic ideas could be integrated between both cultures to create something new and beautiful, which inspired me to make my own clay creation of a mosque covered in different Hindu symbols, such as the lotus flower, the symbol for “Om,” and the Hamsa, the open palm with an evil eye that wards away evil.

I find that this article and the idea of cultural integration in the medium of architecture and aesthetics aptly encapsulates the general theme of cultural mixing in Muslim-ruled South Asia that we have discussed throughout the course. Notions such as the Prophet Muhammad becoming an avatara of the Hindu god Vishnu, all the Hindu gods being viewed as prophets that came before the time of Muhammad, and even the mystical view of Akbar that Islam and Hinduism – and perhaps all religions for that matter – come from the same basic faith, but are just different pieces and manifestations of it, all reflect this idea that Muslim and Hindu cultures need not be separate, but instead can come together to create something new and perhaps better.

Another perfect example of the confluence of local Indic culture and that of the Turko-Persian world lies in the Asani article, “The Bridegroom Prophet in Medieval Sindhi Poetry.” The article describes how the local Sindhi tradition of the story of a virahini, or “a loving and yearning young woman” (Asani 214) was combined with stories of the Prophet Muhammad and one’s relationship to God to create poetry that reflects one’s soul as a woman longing to be reunited and wedded to her bridegroom, Muhammad, such that she may grow closer to God. I felt it quite fitting, in the theme of the mixing of cultures to create a common ground, to reflect a verse of this poetry by singing it to the tune of “Silent Night,” which of course discusses the story of Christ’s birth and God’s descent to Earth to atone for our sins and open the gates of Heaven to just believers. As I had mentioned in my initial response to this reading earlier in the course, I find an interesting parallel between Jesus and Muhammad as being the sort of bridges between one’s soul and God, though they operate on different kinds of love to do so: in the case of Christianity, a Father-child relationship, while in the case of Islam, such as with the bridegroom, it is a more romantic love and longing for God. Nonetheless, I think this exercise made me truly realize just how much each religion and culture can learn from one another, as the combination of seemingly different ideas sometimes makes all the sense in the world.

However, of course, as we have seen time and time again, things do not always mold together so nicely, as oftentimes people have disagreements on how to practice a religion or what the true nature of that religion is. This became abundantly apparent in all we learned throughout the semester concerning Muslim reformist and revival movements in South Asia, as well as the different sects and schools of thought within Islam in general. This was yet another new notion that had never occurred to me. For instance, growing up all my life, it made complete sense to me that my faith, Catholicism, was not the same as Lutheranism, or Methodism, or especially Baptism, even though they are all just different forms of Christianity, but it never occurred to me that this could be the case for Islam – I suppose I just figured everyone followed the Qu’ran and lived happily ever after.

Naturally, I quickly found this not to be the case, first and foremost in “A Nineteenth Century Indian ‘Wahhabi’ Tract Against the Cult of Saints: Al-Balagh al-Mubin” by Mark Gaborieau. Here, through a book Al-Balagh al-Mubin, supposedly written by a Muslim ruler Shah Walliulah, the issue of saint worship came to the forefront of the debate within the South Asian Muslim world, as members of the “Wahhabi” movement advocated against the cult of saints, calling them heretical by praying to anyone who isn’t God. Furthermore, they suggested the practice was idolatry and polytheistic, likening saint-worshippers to Hindus, which is a further attempt to solidify the identity of what is truly “Muslim” as opposed to what is “non-Muslim.” In my response, a video involving a discussion on the matter between the Grinch, a Wahhabi, and his dog Max, a saint-worshipper, on the issue, I reach the conclusion that sometimes, just as is the case of the different religions within Christianity, people must agree to disagree, as people may choose to express their faith in a variety of ways that may or may not be exactly like those of others. Considering especially that Shah Walliulah likely did not write the text, but instead took the approach that as long as the saint-worshippers were praying through the saints rather than to them, I would hope this conclusion at the end of the video of tolerance between practices of one faith can eventually be reached.

Yet another example of divisive reform movements lies in Freeland Abbott’s article, “The Jihad of Sayyid Ahmad Shahid,” in which Abbott describes how the Sayyid, in response to growing British power in South Asia and thus the decreasing prominence of Muslims in the subcontinent, led an unsuccessful reform movement of jihad against the Sikhs. As power was generally believed to coincide with the grace of God, the gradual loss of Muslim power in South Asia to the British sparked a lot of debate about where and how Muslims had gone astray. The Sayyid wanted to revert back to the pure form of Islam that Muhammad had created, without all the modern changes of his day, and tried to unite South Asian Muslims through jihad to regain power. Thus, in a fashion very different to Wahhabism, which appears more ideological, Sayyid Ahmad Shahid took a more hands-on approach. In making my response, a poem in the voice of the Sayyid offering a call to arms to all Muslim, I realized that I now understand jihad far better than I had before taking this class, for what was once a word I associated with hatred and terrorism due to today’s media, I now realized was a call for reform, for a cause far greater than just promoting violence. So, given the Sayyid and the Shah Walliulah article, I now find that having taken this course I have a firmer grasp of the different views and opinions that have always persisted throughout the Muslim world, as opposed to just viewing Islam as one monolithic religion with lots of violent people, as it often seems in the media.

Finally, towards the end of the semester, we touched upon the relationship between religion and politics, particularly in the modern world, and how Islam and Hinduism fit in today’s South Asia with the advent of new media technology such as television and the Internet. One major area in the realm of Islam and politics about which I knew surprisingly little was the formation and founding of Pakistan, the ideological basis of which fascinated me, as I did not know it was supposed to be a secular government as opposed to a theocracy. What really piqued my interest, however, was the use of Islam in Pakistani politics once the country had already been formed. This came about in Esposito’s article, “Islam and Democracy, ” which discussed the changes of power in Pakistan’s history.

Pakistan offers a unique look at an attempt to form a nation on the basis of a common religion, which brought about all sorts of issues and questions – If it is an Islamic Republic, does that mean a country the laws of which are governed by the Qu’ran, or a country that merely operates justly and offers up a safe and secure place for Muslims to live? If Islam is to be part of the government, to what extent, and considering no one can agree on what exactly “Islam” is, whose opinion does the government follow? What seems like such a novel idea – taking all the Muslims out of India to make a Muslim homeland in a new country – is clearly muddled with a lot of questions, and even though the majority of people in the country practice the same religion, the debates between these religious and political issues proved divisive nonetheless. Islam became such a huge part of public discourse that by the time of Zia ul-Haq’s military rule in the 1970’s, Islam became a political tool of the state rather than merely a religion. As Esposito writes, “The politicization of Islam in Pakistan was evident in politics, law, economics, and social life. Islamic symbols and criteria were often invoked so successfully by the government that those who opposed Zia were forced to cast their arguments in an Islamic mold” (Esposito 109). In this way, the state was able to control the people of Pakistan by somewhat turning their own religion against them, as evidenced in my response, a drawing of a huge mosque and the Pakistani flag looming over the shadows of citizens. Thus, Pakistan offers a prime example of how the state, especially one that is founded as a religious homeland, can use religion to gain and retain political power, a notion that I find frightening as an American who believes church and state should not intertwine.

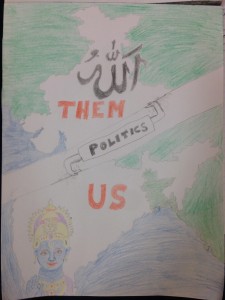

However, the politicization of religion does not just occur at the hands of the state, but also at the hands of the media to influence the masses. Such is the case in India, as exposed in the article “Modern Hate,” by Susan and Lloyd Rudolph. The discussion in this article, which describes how the modern tensions between Hindus and Muslims in India does not necessarily stem from issues in the past, but rather issues in the present, truly opened my eyes to the issues of identity in the modern world. Due to modern forms of mass media, so many people can be connected at once – and indeed, the world feels like a much smaller place because of it. So what do people do? They see others that are similar to them, and others that are not, and everybody likes to be part of a team; thus, as evidenced quite literally in my response, a drawing of a divided India, identities form in the style of “us” vs. “them” in order to categorize one another. Suddenly, whereas Muslims and Hindus largely lived in peace for long periods of time in South Asia, huge rifts are created that result in riots, deaths, the tearing down of mosques in the name of Lord Ram, retaliation and cross-retaliation, the cycle goes on and on. As the Rudolph’s suggest, it appears that a general trend is ensuing in modern times where politics is less about ideology and more about identity, as they write, “Directly and indirectly, religion, ethnicity and gender increasingly define what politics is about, from the standing of Muslim personal law and monuments in India to Muslim and Christian Serbs and Croats sharing sovereignty in Bosnia…” (Rudolph 29). Therefore it would appear that, contrary to popular belief, even as the world is growing more “tolerant” of itself in this day and age, and may feel like a smaller place, it seems as though it has never been so divided.

In the end, if anything, I feel that this course has taught me how to be a good citizen of the world, as I feel that I now grasp how important it is to understand the religion and religious history of a country to understand it in the present day, whether it is India, Pakistan, or even America. This course has shown me how diverse Islam truly is, how much debate has gone on concerning the practice of the religion throughout history and which continues to this day, and just how much religion influences our identities and the world in which we live. Just a few more things to consider when going to Mass (usually) every Sunday.