Is the pot calling the kettle black?

February 25th, 2012

|

| “…the interpersonal processes that a student goes through…” Harvard students (2008) by E>mar via flickr. Used by permission (CC by-nc-nd) |

Is the pot calling the kettle black? Oh sure, journal prices are going up, but so is tuition. How can universities complain about journal price hyperinflation if tuition is hyperinflating too? Why can’t universities use that income stream to pay for the rising journal costs?

There are several problems with this argument, above and beyond the obvious one that two wrongs don’t make a right.

First, tuition fees aren’t the bulk of a university’s revenue stream. So even if it were true that tuition is hyperinflating at the pace of journal prices, that wouldn’t mean that university revenues were keeping pace with journal prices.

Second, a journal is a monopolistic good. If its price hyperinflates, buyers can’t go elsewhere for a substitute; it’s pay or do without. But a college education can be arranged for at thousands of institutions. Students and their families can and do shop around for the best bang for the buck. (Just do a search for “best college values” for the evidence.) In economists’ parlance, colleges are economic substitutes. So even if it were true that tuition at a given college is hyperinflating at the pace of journal prices, individual students can adjust accordingly. As the College Board says in their report on “Trends in College Pricing 2011”:

Neither changes in average published prices nor changes in average net prices necessarily describe the circumstances facing individual students. There is considerable variation in prices across sectors and across states and regions as well as among institutions within these categories. College students in the United States have a wide variety of educational institutions from which to choose, and these come with many different price tags.

Third, a journal article is a pure information good. What you buy is the content. Pure information goods include things like novels and music CDs. They tend to have high fixed costs and low marginal costs, leading to large economies of scale. But a college education is not a pure information good. Sure, you are paying in part to acquire some particular knowledge, say, by listening to a lecture. But far more important are the interpersonal processes that a student participates in: interacting with faculty, other instructional staff, librarians, other students, in their dormitories, labs, libraries, and classrooms, and so forth. It is through the person-to-person hands-on interactions that a college education develops knowledge, skills, and character.

This aspect of college education has high marginal costs. One would not expect it to exhibit the economies of scale of a pure information good. So even if it were true that tuition is hyperinflating at the pace of journal prices, that would not take the journals off the hook; they should be able to operate with much higher economies of scale than a college by virtue of the type of good they are.[1]

Which makes it all the more surprising that the claims about college tuition hyperinflating at the rate of journals are, as it turns out, just plain false.

Let’s look at what the average Harvard College student pays for his or her education. When we talk about journal prices hyperinflating, we’re not just talking about list prices but about the net prices that libraries actually pay for the journals. If list prices hyperinflate but publishers provide discounts that moderate the inflation, you can’t hold the list prices against them. But the hyperinflation in serials prices has been in net costs—for instance, as recorded by the annual ARL serials price surveys.

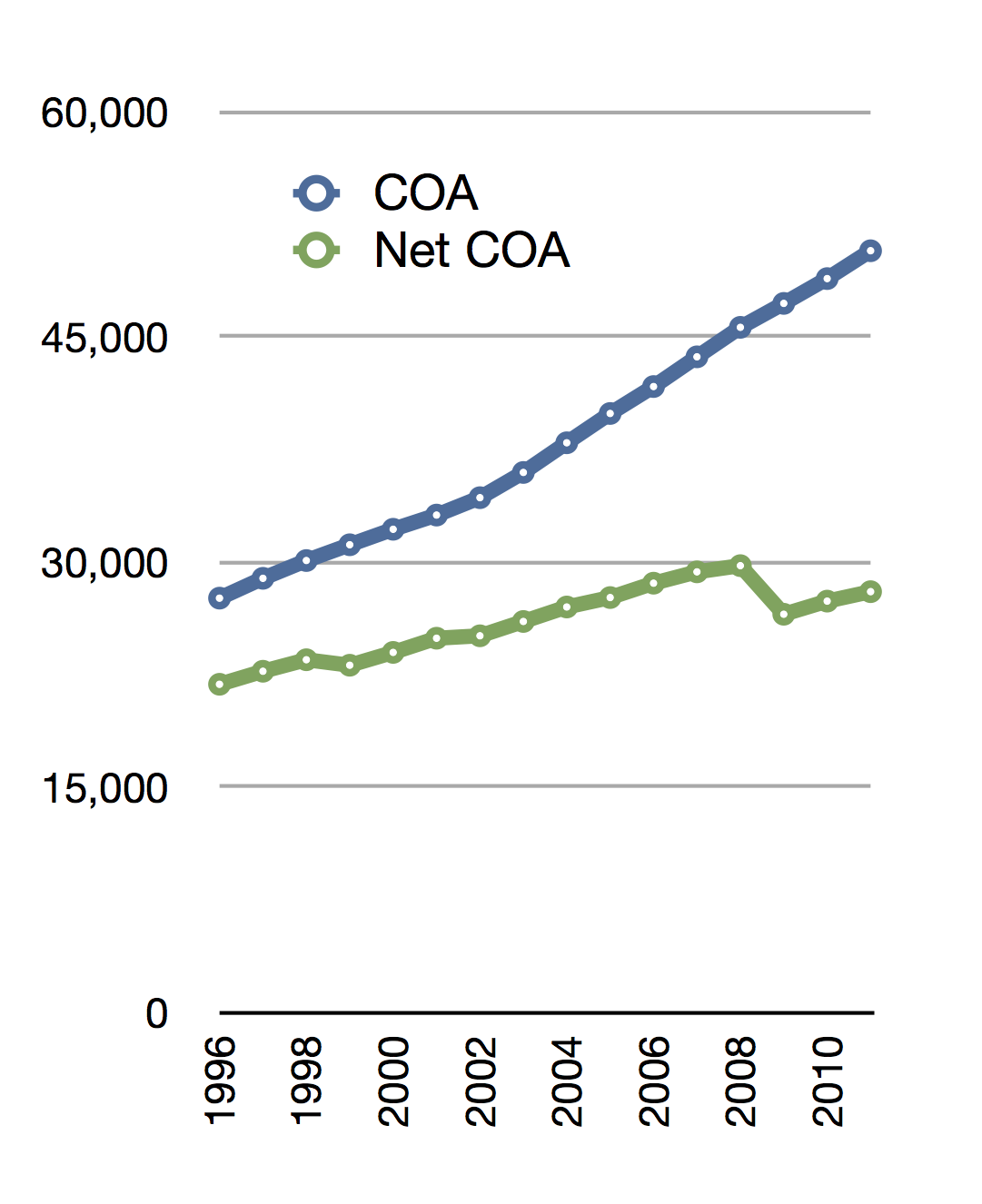

Similarly for colleges we need to look at net prices, not list prices. The list price of a college education, the cost of attendance (COA) is the published tuition and fees, room and board; the net price subtracts whatever financial aid the college provides. There is a substantial difference between the two, as this chart shows:

The green line, the average net COA (in green) has increased, surely, but not nearly as quickly as the list COA (in blue). And it is the net COA that we are concerned with.

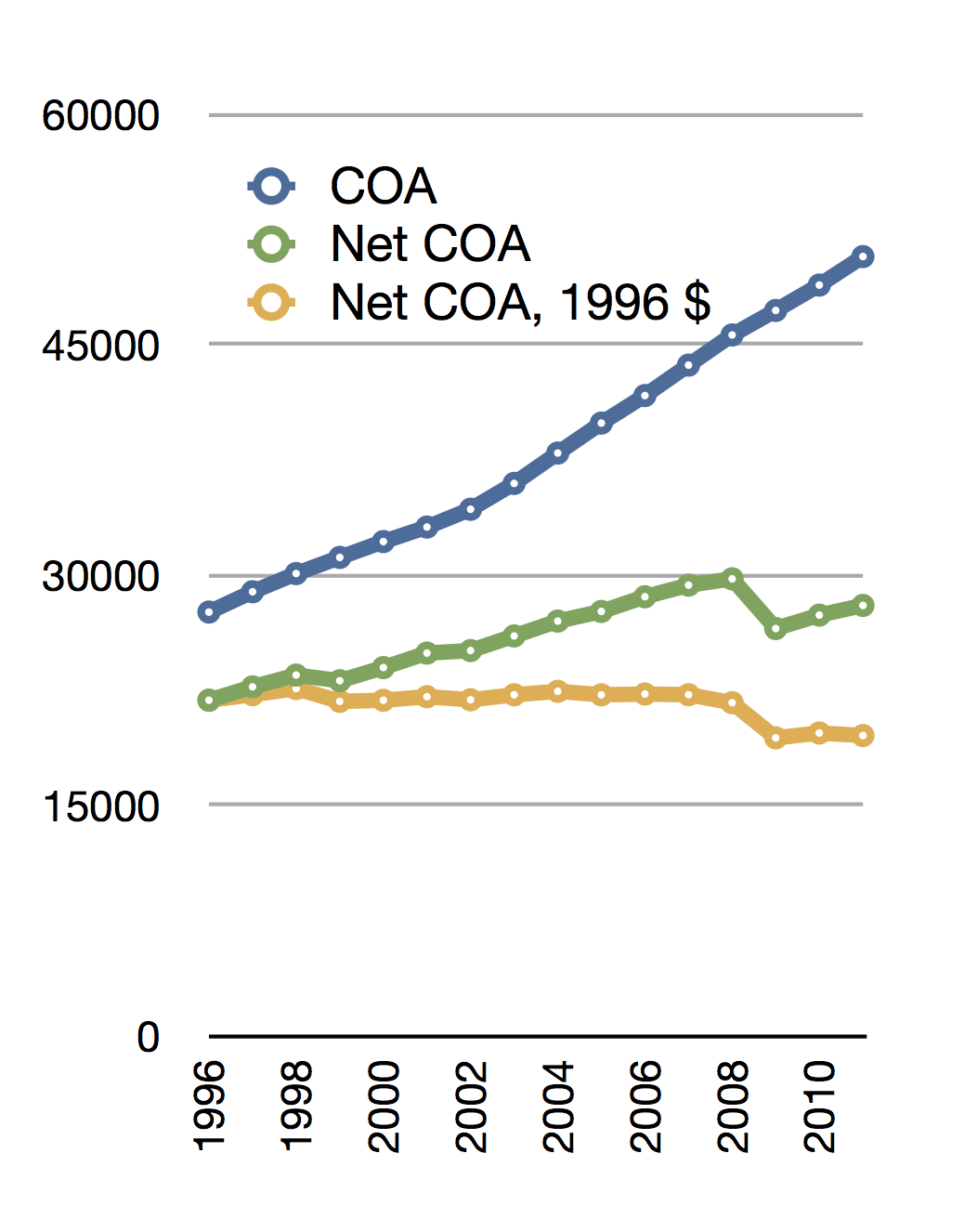

We also need to make sure that we are comparing costs appropriately over time. We should compare in inflation-adjusted dollars. Looking at the net COA normalized against the consumer price index (CPI-U, in 1996 dollars), things look quite different:

Net Harvard COA has been basically flat for the last 15 years or so, with, in fact, a dip in the last few years.

Now, we can place the inflation-adjusted net COA on the same chart as inflation-adjusted net serials expenditures to gauge the comparison between the two. (I normalize them to 1996 = 1 so that the changes over time can be compared.)

Is this unique to Harvard? Certainly there is a lot of variation in net COA among different groups of colleges. Public universities have been losing large amounts of their state subsidies over the last few years, leading to real net COA increases. But those tuition increases result from a subsidy being reduced; they aren’t generating windfall revenue increases to pay for journal price increases. Private four-year colleges and universities have not had huge increases in revenues from students. The College Board’s study shows that over the time period they looked at

Average published tuition and fees at private nonprofit four-year colleges and universities are about $3,730 higher (in 2011 dollars) in 2011-12 than they were in 2006-07, but the average net tuition paid by full-time students in this sector declined by $550 in inflation-adjusted dollars over this five-year period. (College Board, “Trends in College Pricing 2011”. Emphasis added.)

You can be the judge as to whether a tuition decrease of $100 per year in real dollars constitutes hyperinflation at journal-price levels.

The hyperinflation in journal prices looks especially bad when we compare it against other pure information goods, say, music CDs. The information technology revolution has led to tremendous efficiencies in generating and distributing information goods. In the presence of competition, this leads in general to great efficiencies and price reductions, a phenomenon we see clearly in CD price history. Why hasn’t the journal publishing industry been able to generate similar efficiency gains over time? Shouldn’t journal prices be going down, not up?

[Update May 15, 2012: NPR’s Planet Money podcast for May 11, 2012 featured a story (“The Real Price of College“) on the divergence of list and net college prices stating the same conclusion of stable net COA over the last decade. They go into great detail about why list prices are increasing while net prices remain roughly constant.]

Data sources:

Serials expenditure data are from the ARL Annual Surveys.

Harvard COA and net COA data are courtesy of Harvard’s Office of Institutional Research.

CD prices are from the RIAA report “CDs are a better value than ever!“.

Consumer price index data are from the US Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[1]You may say that this aspect of college education is a waste of money. The Khan Academy is able to teach algebra at essentially zero marginal cost. This is true, and its tuition is not hyperinflating either. If students want that kind of education, that’s fine, but for better or worse that is not the type of education provided by institutions that have libraries that subscribe to journals, so is irrelevant to this argument.