Open letter on the Access2Research White House petition

May 21st, 2012

I just sent the email below to my friends and family. Feel free to send a similar letter to yours.

You know me. I don’t send around chain letters, much less start them. So you know that if I’m sending you an email and asking you to tell your friends, it must be important.

This is important.

As taxpayers, we deserve access to the research that we fund. It’s in everyone’s interest: citizens, researchers, government, everyone. I’ve been working on this issue for years. I recently testified before a House committee about it.

Now we have an opportunity to tell the White House that they need to take action. There is a petition at the White House petition site calling for “President Obama to act now to implement open access policies for all federal agencies that fund scientific research.” If we get 25,000 signatures by June 19, 2012, the petition will be placed in the Executive Office of the President for a policy response.

Please sign the petition. I did. I was signatory number 442. Only 24,558 more to go.

Signing the petition is easy. You register at the White House web site verifying your email address, and then click a button. It’ll take five minutes tops. (If you’re already registered, you’re down to ten seconds.)

Please sign the petition, and then tell those of your friends and family who might be interested to do so as well. You can inform people by tweeting them this URL <http://bit.ly/MAbTHG> or posting on your Facebook page or sending them an email or forwarding them this one. If you want, you can point them to a copy of this email that I’ve put up on the web at <http://bit.ly/J8EmyD>.

Since I’ve just requested that you send other people this email (and that they do so as well), I want to make sure that there’s a chain letter disclaimer here: Do not merely spam every email address you can find. Please forward only to those people who you know well enough that it will be appreciated. Do not forward this email after June 19, 2012. The petition drive will be over by then. By all means before forwarding the email check the White House web link showing the petition at whitehouse.gov to verify that this isn’t a hoax. Feel free to modify this letter when you forward it, but please don’t drop the substance of this disclaimer paragraph.

You can find out more about the petition from the wonderful people at Access2Research who initiated it, and you can read more about my own views on open access to the scholarly literature at my blog, the Occasional Pamphlet.

Thank you for your help.

Stuart M. Shieber

Welch Professor of Computer Science

Director, Office for Scholarly Communication

Harvard University

The new Harvard Library open metadata policy

April 27th, 2012

|

| “Old Books” photo by flickr user Iguana Joe, used by permission (CC-by-nc) |

Earlier this week, the Harvard Library announced its new open metadata policy, which was approved by the Library Board earlier this year, along with an initial two metadata releases. The policy is straightforward:

The Harvard Library provides open access to library metadata, subject to legal and privacy factors. In particular, the Library makes available its own catalog metadata under appropriate broad use licenses. The Library Board is responsible for interpreting this policy, resolving disputes concerning its interpretation and application, and modifying it as necessary.

The first releases under the policy include the metadata in the DASH repository. Though this metadata has been available through open APIs since early in the repository’s history, the open metadata policy makes clear the open licensing terms that the data is provided under.

The release of a huge percentage of the Harvard Library’s bibliographic metadata for its holdings is likely to have much bigger impact. We’ve provided 12 million records — the vast majority of Harvard’s bibliographic data — describing Harvard’s library holdings in MARC format under a CC0 license that requests adherence to a set of community norms that I think are quite reasonable, primarily calling for attribution to Harvard and our major partners in the release, OCLC and the Library of Congress.

OCLC in particular has praised the effort, saying it “furthers [Harvard’s] mandate from their Library Board and Faculty to make as much of their metadata as possible available through open access in order to support learning and research, to disseminate knowledge and to foster innovation and aligns with the very public and established commitment that Harvard has made to open access for scholarly communication. I’m pleased to say that they worked with OCLC as they thought about the terms under which the release would be made.” We’ve gotten nice coverage from the New York Times, Library Journal, and Boing Boing as well.

Many people have asked what we expect people to do with the data. Personally, I have no idea, and that’s the point. I’ve seen over and over that when data is made openly available with the fewest impediments — legal and technical — people are incredibly creative about finding innovative uses for the data that we never could have predicted. Already, we’re seeing people picking up the data, exploring it, and building on it.

- The Digital Public Library of America is making the data available through an API that provides data in a much nicer way than the pure MARC record dump that Harvard is making available.

- Within hours of release, Benjamin Bergstein had already set up his own search interface to the Harvard data using the DPLA API.

- Carlos Bueno has developed code for the Harvard Library Bibliographic Dataset to parse its “wonky” MARC21 format, and has open-sourced the code.

- Alf Eaton has documented his own efforts to work with the bibliographic dataset, providing instructions for downloading and extracting the records and putting up all of the code he developed to massage and render the data. He outlines his plans for further extensions as well.

(I’m sure I’ve missed some of the ways people are using the data. Let me know if you’ve heard of others, and I’ll update this list.)

As I’ve said before, “This data serves to link things together in ways that are difficult to predict. The more information you release, the more you see people doing innovative things.” These examples are the first evidence of that potential.

John Palfrey, who was really the instigator of the open metadata project, has been especially interested in getting other institutions to make their own collection metadata publicly available, and the DPLA stands ready to help. They’re running a wiki with instructions on how to add your own institution’s metadata to the DPLA service.

It’s hard to list all the people who make initiatives like this possible, since there are so many, but I’d like to mention a few major participants (in addition to John): Jonathan Hulbert, Tracey Robinson, David Weinberger, and Robin Wendler. Thanks to them and the many others that have helped in various ways.

Statement before the House Science Committee

March 30th, 2012

|

| “Majesty of Law” Statue in front of the Rayburn House Office Building in Washington, D.C., photo by flickr user NCinDC, used by permission (CC-by-nd) |

Here is my written testimony filed in association with my appearance yesterday at the hearing on “Federally Funded Research: Examining Public Access and Scholarly Publication Interests” before the Subcommittee on Investigations and Oversight of the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology. My thanks to Chairman Broun, ranking member Tonko, and the committee for allowing me the opportunity to speak with them today.

[Update 3/30/12: Coverage from Chronicle of Higher Education. Update 4/2/12: Video of the session is available from the House Science Committee as well.]

Read the rest of this entry »

An efficient journal

March 6th, 2012

|

| “You seem to believe in fairies.” Photo of the Cottingley Fairies, 1917, by Elsie Wright via Wikipedia. |

Aficionados of open access should know about the Journal of Machine Learning Research (JMLR), an open-access journal in my own research field of artificial intelligence, a subfield of computer science concerned with the computational implementation and understanding of behaviors that in humans are considered intelligent. The journal became the topic of some dispute in a conversation that took place a few months ago in the comment stream of the Scholarly Kitchen blog between computer science professor Yann LeCun and scholarly journal publisher Kent Anderson, with LeCun stating that “The best publications in my field are not only open access, but completely free to the readers and to the authors.” He used JMLR as the exemplar. Anderson expressed incredulity:

I’m not entirely clear how JMLR is supported, but there is financial and infrastructure support going on, most likely from MIT. The servers are not “marginal cost = 0” — as a computer scientist, you surely understand the 20-25% annual maintenance costs for computer systems (upgrades, repairs, expansion, updates). MIT is probably footing the bill for this. The journal has a 27% acceptance rate, so there is definitely a selection process going on. There is an EIC, a managing editor, and a production editor, all likely paid positions. There is a Webmaster. I think your understanding of JMLR’s financing is only slightly worse than mine — I don’t understand how it’s financed, but I know it’s financed somehow. You seem to believe in fairies.

Since I have some pretty substantial knowledge of JMLR and how it works, I thought I’d comment on the facts of the matter. Read the rest of this entry »

Switching to open access for the new year

January 4th, 2012

|

| “…time to switch…” A very old light switch (2008) by RayBanBro66 via flickr. Used by permission (CC by-nc-nd) |

The journal Research in Learning Technology has switched its approach from closed to open access as of New Year’s 2012. Congratulations to the Association for Learning Technology (ALT) and its Central Executive Committee for this farsighted move.

This isn’t the first journal to make the switch. The Open Access Directory lists about 130 of them. In my own research field, the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) converted its flagship journal Computational Linguistics to OA as of 2009, and has just announced a new open-access journal Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Each such transition is a reminder of the trajectory that journal publishing ought to head.

The ALT has done lots of things right in this change. They’ve chosen the ideal licensing regime for papers, the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license. They’ve jettisoned one of the largest commercial subscription journal publishers, and gone with a small but dedicated professional open-access publisher, Co-Action Publishing. They’ve opened access to the journal retrospectively, so that the entire archive, back to 1993, is available from the publisher’s web site.

Here’s hoping that other scholarly societies are inspired by the examples of the ALT and ACL, and join the many hundreds of scholarly societies that publish their journals open access. It’s time to switch.

Clarifying the Harvard policies: a response

December 2nd, 2011

My friend and ex-colleague Matt Welsh has an interesting post supporting the Research Without Walls pledge, in which he talks about the Harvard open-access policies. He says:

Another way to fight back is for your home institution to require all of your work be made open. Harvard was one of the first major universities to do this. This ambitious effort, spearheaded by my colleague Stuart Shieber, required all Harvard affiliates to submit copies of their published work to the open-access Harvard DASH archive. While in theory this sounds great, there are several problems with this in practice. First, it requires individual scientists to do the legwork of securing the rights and submitting the work to the archive. This is a huge pain and most folks don’t bother. Second, it requires that scientists attach a Harvard-supplied “rider” to the copyright license (e.g., from the ACM or IEEE) allowing Harvard to maintain an open-access copy in the DASH repository. Many, many publishers have pushed back on this. Harvard’s response was to allow its affiliates to get an (automatic) waiver of the open-access requirement. Well, as soon as word got out that Harvard was granting these waivers, the publishers started refusing to accept the riders wholesale, claiming that the scientist could just request a waiver. So the publishers tend to win.

I wrote a response to his post, clarifying some apparent misconceptions about the policy, but it was too long for his blogging platform’s comment system, so I decided to post it here in its entirety. Here it is:

There’s a lot to like about your post, and I agree with much of what you say. But I’d like to clarify some specific issues about the Harvard open-access policies, which are in place at seven of the Harvard schools as well as MIT, Duke, Stanford, and elsewhere.

The policy has two aspects. First, the policy commits faculty to (as you say) “submitting the work to the archive”, that is, providing a copy of the final manuscript of each article, to be deposited into Harvard’s DASH open-access repository. Doing so involves filling out a web form with metadata about the article and uploading a file. But if that is too much trouble, we provide a simpler web form that is tantamount to just uploading the file. Or you can email the file to the OSC. Or one of our “open-access fellows” can make the deposit on your behalf. We also harvest articles from other repositories such as PubMed Central and arXiv. I can’t imagine that providing the articles is “a huge pain”.

Second, by virtue of the policy, Harvard faculty grant a nonexclusive transferable license to the university in all our scholarly articles. This license occurs as soon as copyright vests in the article, so it predates and therefore dominates any later transfer of copyright to a publisher. Since the policy license is transferable, the university can and does transfer it back to the author, so the author automatically retains rights in each article, without having to take any further action. Because of this policy, the “legwork of securing the rights” is actually eliminated. By doing nothing at all, the author retains rights in the article.

You mention attaching a rider to publication agreements. Although we provide an addendum generator to generate such riders, and we recommend that authors use them, attaching an addendum is not required to retain rights. The only point of the addendum is to alert the publisher that the author has already given Harvard non-exclusive rights to the article (though publishers undoubtedly are already aware of the fact; the policy and its license have been widely publicized).

Because we want the policy to work in the interest of faculty and guarantee the free choice of faculty as to the disposition of their works, the license is waivable at the sole discretion of the author. Thus, rights retention moves from an opt-in regime without the policy to an opt-out regime with the policy. The waiver aspect of the policy was not a response to publisher pushback, but has in fact been in the policies from the beginning. The waiver was intended to preserve complete freedom of choice for authors in rights retention.

As is found in many areas (organ donation, 401K participation), participation tends to be much higher with opt-out than opt-in systems, and that holds for rights retention as well. We have found that the waiver rate is extraordinarily low, contra your assumption. For FAS, we estimate it at perhaps 5% of articles. In total, the number of waivers we have issued is in the very low hundreds, out of the many thousands of articles that have been published by Harvard faculty since the policy was in force. MIT has tracked the waiver rate more accurately, and has reported a 1.5% waiver rate. So for well over 90% of articles, authors are retaining broad rights to use their articles.

The statement that “Many, many publishers have pushed back on this” is false. Less than a handful of publishers have established systematic policies to require waivers of the license, which accounts for the exceptionally low waiver rate. Indeed, over a third of all waivers are attributable to a single journal.

The Harvard approach to rights retention and open-access provision for articles is not a silver bullet to solve all problems in scholarly publishing. It has a limited goal: to provide an alternate venue for openly disseminating our articles and to retain the rights to do so. It is extremely successful at that goal. Many thousands of articles have been deposited in DASH, accounting for over half a million downloads. Nonetheless, other efforts need to be made to address the underlying market dysfunction in scholarly publishing, and we are actively engaged there too. For those interested in what we’re up to along those lines, I recommend taking a look at the various posts at my blog, The Occasional Pamphlet, which discusses issues of open access and scholarly communication more generally.

How should funding agencies pay open-access fees?

November 16th, 2011

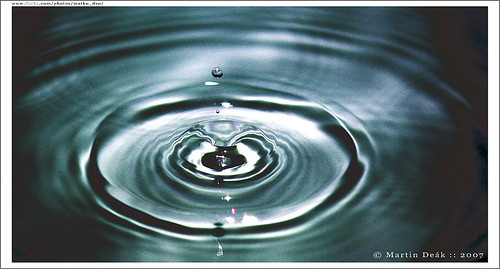

|

| “…a drop in the bucket.” Drop I (2007) by Delox – Martin Deák via flickr. Used by permission (CC by-nc-nd) |

At the recent Berlin 9 conference, there was much talk about the role of funding agencies in open-access publication, both through funding-agency-operated journals like the new eLife journal and through direct reimbursement of publication fees. I’ve written in the past about the importance of universities underwriting open-access publication fees, but only tangentially about the role of funding agencies. To correct that oversight, I provide in this post my thoughts on how best to organize a funding agency’s open-access underwriting system.

The motivation for underwriting publication fees is simple: Publishers provide valuable services to authors: management of peer review; production (copy-editing and typesetting); filtering, branding, and imprimatur. Although access to scholarly articles can now be provided at essentially zero marginal cost through digital networks, some means for paying for these so-called first-copy costs needs to be found in order to preserve these services. The natural business model is the open-access journal funded by article processing fees. (Although most current open-access journals charge no article processing fees, I will abuse the term “open-access journal” for this model.) Open-access (OA) journals are no longer an oddity, a fringe phenomenon. The largest scholarly journal on earth, PLoS ONE, is an OA journal. Major publishers — Springer, Elsevier, SAGE, Nature Publishing Group — are now publishing OA journals.

However, OA journals are currently at a significant disadvantage with respect to subscription journals, because universities and funding agencies subsidize the costs of subscription journals in such a way that authors do not need to trade off money used for the subsidy against money used for other purchases. In particular, subscription fees are paid by universities through their library budgets and by funding agencies through their overhead payments that fund those libraries. Authors do not see, let alone attend to, these costs. In such a situation, an author is inclined to publish in a subscription journal, where they do not need to use any moneys that could otherwise be applied to other uses, rather than an OA journal that requires payment of a publication fee. And if authors are unwilling to publish in open-access journals because of the fees, publishers — even those interested and motivated to switch to an OA revenue model — are unable to do so.

The solution is clear: universities and funding agencies should underwrite reasonable OA publication fees just as they do subscription fees. But how should this be done? Each kind of institution needs to provide its fair share of support.

As I’ve written about before, universities can underwrite processing fees on behalf of their faculty, and do so in a way that does not reintroduce a moral hazard, by reimbursing faculty for OA publication fees up to a fixed cap per year. Since these funds can only be used for open access fees, they can’t be traded off against other purchases, so they don’t provide a disincentive against open access journals. On the other hand, since these funds are limited (capped), they provide a market signal to motivate choosing among open access journals so that the economic incentives will militate toward low-cost high-service open access journals.

This is the argument for the Compact for Open-Access Publishing Equity (COPE), a commitment by universities to establish mechanisms for underwriting OA publication fees. COPE has grown well beyond its initial five signatories and is supported by a wide range of institutions and people. Harvard and other COPE signatories have already set up such OA funds, which work in just this way.

Many COPE-compliant OA funds don’t underwrite articles that were developed under research grants, under the view that such funding is the responsibility of the granting institutions. COPE calls for universities to do their fair share of paying OA fees, no less, but no more. Funding agencies need to underwrite their share of OA fees as well, and crucially should do so in a way that respects several important criteria:

- They level the playing field completely, at least for cost-efficient OA journals.

- They recognize that publication of research results often occurs after grants have ended.

- They provide incentive for publishers to switch revenue model to the OA publication fee model, or at least provide no disincentive.

- They avoid the moral hazard of insulating authors from the costs of their publishing.

- They don’t place an undue burden on funders that would require reducing the impact of research they fund.

Of course, many funders already allow grantees to pay for OA publication fees from their grants. But this method falls afoul of some of these criteria. With respect to criterion (1), grantees are forced to trade off uses of grant moneys to pay OA fees against uses to pay for other research expenses, providing incentive to publish in subscription-fee journals where these costs are hidden. This approach maintains the tilted playing field against OA journals. With respect to criterion (2), because the funds must be expended during the granting period, grantees must predict ahead of time how many articles they will be publishing in OA journals, where they will be publishing them, and those articles must be completed and accepted for publication by the end of the granting period.

The mechanism that satisfies these criteria is for funding agencies to provide non-fungible funds specifically for OA publication fees, funds that are not usable for purchasing other grant-related materials. Funders would establish a policy that grantees could be reimbursed for OA publication fees for articles based on grant-funded research at any time during or after the period of the grant. This satisfies criterion (1) because grantees would no longer have to pay publication fees out of pocket or from grant funds that could be used otherwise. It satisfies criterion (2) because payments can be provided after the end of the grant. (If desired, the delay after the grant ends can be limited to, say, a year or two.) A reasonable requirement for reimbursement of publication fees would be that the article explicitly acknowledge the grant as a source of research funding.

Wellcome Trust already uses a similar incremental funding system. However, they (inadvisably in my mind) allow the funds to apply to so-called hybrid publication fees, where an additional fee can be paid to make a single article available open access. These reimbursements should be limited to publication fees for true OA journals, not hybrid fees for subscription journals. Willingness to pay hybrid fees provides an incentive for a publisher to maintain the subscription revenue model for a journal, because the publisher can acquire these funds without converting the journal as a whole to open access. Eschewing hybrid fees is necessary to satisfy criterion (3).

If funders were willing to pay arbitrary amounts for publication fees without limit, a new moral hazard would be introduced into the publishing market. Authors would become price-insensitive and hyperinflation of publication fees would be possible. To retain a functioning market in publication fees, we must be careful in designing the reimbursement scheme for OA journals; we need to make sure that there is still some scarce resource that authors must manage. This can be achieved in a couple of ways, by capping reimbursements or by copayments. First, reimbursement of OA publication fees can be offered only up to a fixed percentage of the grant amount. By way of example, if an average NIH grant is $300,000 (excluding overhead[1]), a cap of, say, 2% would provide up to $6,000 available for OA fees. (Robert Kiley, Head of Digital Services at the Wellcome Trust, estimates that at present rates all funded papers of the Wellcome Trust could be underwritten for about 1.25% of their total granted funds. In the short run, nowhere near that level of underwriting is necessary, since the number of publication-fee-charging OA journals is so small. In the long run, as competition in the publication fee market increases, this number may well go down.) That would cover two PLoS Biology papers, three BMC papers, four or five PLoS ONE papers, eight or so Hindawi papers. A grantee would apply separately for these funds to reimburse reasonable OA fees. Some grantees might use all of these funds, some none, with most falling in the middle (and currently at the low end); but in any case they would not be usable for other purposes. Since these funds can only be used for OA publication fees, they can’t be traded off against other purchases, so there is no disincentive against selecting OA journals. On the other hand, since these funds are limited (capped), they provide a market signal to motivate choosing among open access journals so that the economic incentives will militate toward low-cost high-service OA journals. (This can’t be repeated often enough.)

Alternatively, a copayment approach can be used to provide economic pressure to keep publication fees down. Reimbursement would cover only part of the fee, at least at the expensive end of such fees. It is important (criterion 1) that for cost-efficient OA journals, authors should not be out of pocket for any fees. Thus, reimbursement should be at 100% for journals charging less than some threshold amount, say, $1,500. (As publishers become more efficient, this threshold can and should be reduced over time.) Above that level, the funder might pay only a proportion of the fee, say, 50%, so that grantees have some “skin in the game” and are motivated to trade off publication fees against quality of publisher services. With these parameters, the payment schedule would provide for the following kinds of payments:

| Publication fee | Funder pays | Author copays | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| $700 | $700 | $0 | typical Hindawi journal, SAGE Open |

| $1350 | $1350 | $0 | PLoS ONE, Scientific Reports |

| $2000 | $1750 | $250 | typical BMC journal |

| $2900 | $2200 | $700 | PLoS Biology |

(What the right parameters of such an approach are may depend on field and may change over time. I don’t propose these as the correct values, but merely provide an example of the workings of such a system.)

These two approaches are complementary. A policy could involve both a per-article copayment and a maximum per-grant outlay.

Finally, criterion (5) calls for implementing such an underwriting scheme as cost-effectively as possible, so that a funder’s research impact is not lessened by paying for publication fees. Indeed, one might expect that impact would be increased by such a move, given that the tiny percentage of funds going to OA fees would mean that those research results were freely and openly available to readers and to machine analysis throughout the world. I would think (and I recall a claim to this effect at Berlin 9) that the impact benefit of providing open access to a funder’s research results is greater than the impact of the marginal funded research grant. To the extent that this is so, it behooves funders to underwrite OA fees even at the expense of funding the incremental research. Nonetheless, there may be no need to forego funding research just to pay OA fees. Suppose that on the average grant incremental funds of $200 are used to pay OA publication fees. (With current availability and usage of OA journals, this is likely an overestimate of current demand for OA fees.) Where would this money come from? To the extent that faculty are publishing in OA journals, funders should not need to underwrite subscription journals, so that their overhead rates can be reduced accordingly. An overhead rate of 67% (Harvard’s current rate) would need to be reduced by a minuscule 0.067% to compensate. (This is not a typo. The number really is 0.067%, not 6.7%.) This constitutes a percentage reduction in overhead of one part in a thousand, a drop in the bucket. In the longer term over several years if usage of the funds rises to, say, $1000 per grant, the overhead rate would need to be reduced by a still tiny 0.33% for cost neutrality. As more OA journals become available and more funds are used, the overhead rate would be adjusted accordingly. If hypothetically all journals became OA, and all articles incurred these charges, the cost per grant might rise higher to Wellcome Trust’s predicted 1.25% (though by this point competition may have substantially reduced the fees), but then, larger reductions in overhead rates would be met by reduced university costs, since libraries would no longer need to pay subscription fees.

One of the nice properties of this approach is that it doesn’t require synchronization of the many actors involved. Each funding agency can unilaterally start providing OA fee reimbursement along these lines. Until a critical mass do so, the costs would be minimal. Once a critical mass is obtained, and journals feel confident enough that a sufficient proportion of their author pool will be covered by such a fund to switch to an open-access revenue model, subscription fees to libraries will drop, allowing for overhead rates to be reduced commensurately to cover the increasing underwriting costs. Each actor — author, funder, publisher, university, library — acts independently, with a market mechanism to move all towards a system based on open access.

It is time for funding agencies to take on the responsibility not only to fund research but its optimal distribution. Part of that responsibility is putting in place an economically sustainable system of underwriting open-access publication fees.

[1]The NIH Data Book reports average grant size for 2010 as around $450,000, which corresponds to something like $270,000 assuming a 67% overhead rate. $300,000 is thus likely on the high side.

Subscription fees as a distribution control mechanism

September 11th, 2011

|

| Stamps to mark “restricted data” (modified from “atomic stamps 1” by flickr user donovanbeeson, used by permission under CC by-nc-sa) |

Ten years ago today was the largest terrorist action in United States history, an event that highlighted the importance of intelligence, and its reliance on information classification and control, for the defense of the country. This anniversary precipitated Peter Suber’s important message, which starts from the fact that access to knowledge is not always a good. He addresses the question of whether open access to the scholarly literature might make information too freely available to actors who do not have the best interests of the United States (or your country here) at heart. Do we really want everyone on earth to have information about public-key cryptosystems or exothermic chemical reactions? Should our foreign business competitors freely reap the fruits of research that American taxpayers funded? He says,

You might think that no one would seriously argue that using prices to restrict access to knowledge would contribute to a country’s national and economic security. But a vice president of the Association of American Publishers made that argument in 2006. He “rejected the idea that the government should mandate that taxpayer financed research should be open to the public, saying he could not see how it was in the national interest. ‘Remember — you’re talking about free online access to the world,’ he said. ‘You are talking about making our competitive research available to foreign governments and corporations.’ “

Suber’s response is that “If we’re willing to restrict knowledge for good people in order to restrict knowledge for bad people, at least when the risks of harm are sufficiently high, then we already have a classification system to do this.” (He provides a more detailed response in an earlier newsletter.) He is exactly right. Placing a $30 paywall in front of everyone to read an article in order to keep terrorists from having access to it is both ineffective (relying on al Qaeda’s coffers to drop below the $30 point is not a counterterrorism strategy) and overreaching (since a side effect is to disenfranchise the overwhelming majority of human beings who are not enemies of the state). Instead, research that the country deems too dangerous to distribute should be, and is, classified, and therefore kept from both open access and toll access journals.

This argument against open access, that it might inadvertently abet competitors of the state, is an instance of a more general worry about open distribution being too broad. Another instance is the “corporate free-riding” argument. It is argued that moving to an open-access framework for journals would be a windfall to corporations (the canonical example is big pharma) who would no longer have to subscribe to journals to gain the benefit of their knowledge and would thus be free-riding. To which the natural response would be “and what exactly is wrong with that?” Scientists do research to benefit society, and corporate use of the fruits of the research is one of those benefits. Indeed, making research results freely available is a much fairer system, since it allows businesses both large and small to avail themselves of the results. Why should only businesses with deep pockets be able to take advantage of research, much of which is funded by the government.

But shouldn’t companies pay their fair share for these results? Who could argue with that? To assume that the subscription fees that companies pay constitute their fair share for research requires several implicit assumptions that bear examination.

Assumption 1: Corporate subscriptions are a nontrivial sum. Do corporate subscriptions constitute a significant fraction of journal revenues? Unfortunately, there are to my knowledge no reliable data on the degree to which corporate subscriptions contribute to revenue. Estimates range from 0% (certainly the case in most fields of research outside the life sciences and technology) to 15-17% to 25% (a figure that has appeared informally and been challenged in favor of a 5-10% figure). (Thanks to Peter Suber for help in finding these references.) None of these estimates were backed up in any way. Without any well-founded figures, it doesn’t seem reasonable to be worrying about the issue. The onus is on those proposing corporate free-riding as a major problem to provide some kind of transparently supportable figures.

Assumption 2: Corporations would pay less under open access. The argument assumes that in an open-access world, journal revenues from corporations would drop, because they would save money on subscriptions but would not be supporting publication of articles through publication fees. That is, corporate researchers “read more than they write.” Of course, corporate researchers publish in the scholarly literature as well (as I did for the first part of my career when I was a researcher at SRI International), and thus would be contributing to the financial support of the publishing ecology. Here again, I know of no data on the percentage of articles with corporate authors and how that compares to the percentage of revenue from corporate subscriptions.

Assumption 3: Corporations shouldn’t be paying less than they now are, perhaps for reasons of justice, or perhaps on the more mercenary basis of financial reality. It is presumed that if corporations are not paying subscription fees (and, again by assumption, publication fees) then academia will have to pick up the slack through commensurately higher publication fees, so the total expenditure by academia will be higher. This is taken to be a bad thing, but the reason for that is not clear. Why is it assumed that the “right” apportionment of fees between academia and business is whatever we happen to have at the moment, resulting as it does from historical happenstance based on differential subscription rates and corporate and university budget decisions? Free riding in the objectionable sense is to get something without paying when one ought to pay. But the latter condition doesn’t apply to the open-access scholarly literature any more than it applies to broadcast television.

Assumption 4: Corporations only support research through subscription fees. However, corporations also provide support for funded research through the corporate taxes that they pay to the government, which funds the research. And this mode of payment has the advantage that it covers all parts of the research process, not just the small percentage that constitutes the publishing of the final results. Corporate taxes constitute some 10% of total US tax revenue according to the IRS, so we can impute corporate underwriting of US-government funded research at that same 10% level. (In fact, since many non-corporate taxes, like FICA taxes, are earmarked for particular programs that don’t fund research, the imputed percentage should perhaps be even higher.) The subscription fees companies pay is above and beyond that. Is the corporate 10% not already a fair share? Might it even be too much?

If we collectively thought that the amount corporations are paying is insufficient, then the right response would be to increase the corporate taxes accordingly, so that all corporations contribute to the underwriting of scientific research that they all would be benefitting from. Let’s take a look at some numbers. The revenue from the 2.5 million US corporations paying corporate tax for 2009 (the last year for which data are available) was about $225 billion. The NSF budget for 2009 was $5.4 billion. So, for instance, a 50% increase in the NSF budget would require increasing corporate tax revenues by a little over 1%, that is, from a 35% corporate tax rate (say) to something like 35.4%. I’m not advocating an increase in corporate taxes for this purpose. First, I’m in no way convinced that corporations aren’t already supporting research sufficiently. Second, there are many other effects of corporate taxes that may militate against raising them. Instead, the point is that it is naive to pick out a single revenue source, subscription fees, as the sum total of corporate support of research.

Assumption 5: Subscription fees actually pay for research, or some pertinent aspect of research. But those fees do not devolve to the researchers or cover any aspect of the research process except for the publication aspect, and publishing constitutes only a small part of the costs of doing research. To avoid disingenuousness, shouldn’t anyone worrying about whether corporations are doing their fair share in underwriting that aspect be worrying about whether they are doing their fair share in underwriting the other aspects as well? Of course, corporations arguably are underwriting other aspects — through internal research groups, grants to universities and research labs, and their corporate taxes (the 10% discussed above). And in an open-access world, they would be covering the publication aspect as well, namely publication fees, through those same streams.

In summary, maintaining the subscription revenue model for reasons of distribution control — whether for purposes of state defense or corporate free-riding — is a misconstruction.

JSTOR opens access to out-of-copyright articles

September 8th, 2011

|

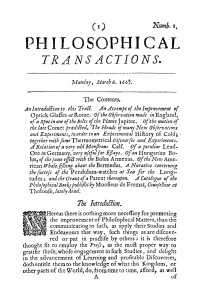

| Cover of the first issue of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, dated March 6, 1665. Available from JSTOR’s Early Journal Content collection. |

JSTOR, the non-profit online journal distributor, announced yesterday that they would be making pre-1923 US articles and pre-1870 non-US articles available for free in a program they call “Early Journal Content”. The chosen dates are not random of course; they guarantee that the articles have fallen out of copyright, so such distribution does not run into rights issues. Nonetheless, that doesn’t mean that JSTOR could take this action unilaterally. JSTOR is further bound by agreements with the publishers who provided the journals for scanning, which may have precluded them contractually from distributing even public domain materials that were derived from the provided originals. Thus such a program presumably requires cooperation of the journal publishers. In addition, JSTOR requires goodwill from publishers for all of its activities, so unilateral action could have been problematic for its long-run viability. (Such considerations may even in part underly JSTOR’s not including all public domain material in the opened collection.)

Arranging for the necessary permissions — whether legal or pro forma — takes time, and JSTOR claims that work towards the opening of these materials started “about a year ago”, that is, prior to the recent notorious illicit download program that I have posted about previously. Predictably, the Twittersphere is full of speculation about whether the actions by Aaron Swartz affected the Early Journal Content program:

@grimmelm: JSTOR makes pre-1923 journals freely available http://about.jstor.org/participate-jstor/individuals/early-journal-content Would this have happened earlier or later w/o @aaronsw?

@mecredis: JSTOR makes all their public domain content available for free: http://about.jstor.org/news-events/news/jstor%E2%80%93free-access-early-journal-content I think this means @aaronsw wins.

@maxkaiser: Breaking: @JSTOR to provide free #openaccess to pre-1923 content in US & pre-1870 elsewhere – @aaronsw case had impact: http://about.jstor.org/news-events/news/jstor%E2%80%93free-access-early-journal-content

@JoshRosenau: JSTOR “working on releasing pre-1923 content before [@aaronsw released lotsa their PDFs], inaccurate to say these events had no impact.”

@mariabustillos: Stuff that in yr. pipe and smoke it, JSTOR haters!! http://bit.ly/qtrxdV Also: how now, @aaronsw?

So, did Aaron Swartz’s efforts affect the existence of JSTOR’s new program or its timing? As to the former, it seems clear that with or without his actions, JSTOR was already on track to provide open access to out-of-copyright materials. As to the latter, JSTOR says that

[I]t would be inaccurate to say that these events have had no impact on our planning. We considered whether to delay or accelerate this action, largely out of concern that people might draw incorrect conclusions about our motivations. In the end, we decided to press ahead with our plans to make the Early Journal Content available, which we believe is in the best interest of our library and publisher partners, and students, scholars, and researchers everywhere.

On its face, the statement implies that JSTOR acted essentially without change, but we’ll never know if Swartz’s efforts sped up or slowed down the release.

What the Early Journal Content program does show is JSTOR’s interest in providing broader access to the scholarly literature, a goal they share with open-access advocates, and even with Aaron Swartz. I hope and expect that JSTOR will continue to push, and even more aggressively, towards broader access to its collection. The scholarly community will be watching.

On guerrilla open access

July 28th, 2011

|

| William G. Bowen, founder of JSTOR |

[Update January 13, 2013: See my post following Aaron Swartz’s tragic suicide.]

Aaron Swartz has been indicted for wire fraud, computer fraud, unlawfully obtaining information from a protected computer, and recklessly damaging a protected computer. The alleged activities that led to this indictment were his downloading massive numbers of articles from JSTOR by circumventing IP and MAC address limitations and breaking and entering into restricted areas of the MIT campus to obtain direct access to the network, for the presumed intended purpose of distributing the articles through open file-sharing networks. The allegation is in keeping with his previous calls for achieving open access to the scholarly literature by what he called “guerrilla open access” in a 2008 manifesto: “We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks.” Because many theorize that Swartz was intending to further the goals of open access by these activities, some people have asked my opinion of his alleged activities.

Before going further, I must present the necessary disclaimers: I am not a lawyer. He is presumed innocent until proven guilty. We don’t know if the allegations in the indictment are true, though I haven’t seen much in the way of denials (as opposed to apologetics). We don’t know what his intentions were or what he planned to do with the millions of articles he downloaded, though none of the potential explanations I’ve heard make much sense even in their own terms other than the guerrilla OA theory implicit in the indictment. So there is a lot we don’t know, which is typical for a pretrial case. But for the purpose of discussion, let’s assume that the allegations in the indictment are true and his intention was to provide guerrilla OA to the articles. (Of course, if the allegations are false, as some seem to believe, then my claims below are vacuous. If the claims in the indictment turn out to be false, or colored by other mitigating facts, I for one would be pleased. But I can only go by what I have read in the papers and the indictment.)

There’s a lot of silliness that has been expressed on both sides of this case. The pro-Swartz faction is quoted as saying “Aaron’s prosecution undermines academic inquiry and democratic principles.” Hunh? Or this one: “It’s incredible that the government would try to lock someone up for allegedly looking up articles at a library.” Swartz could, of course, have looked up any JSTOR article he wanted using his Harvard library privileges, and could even have text-mined the entire collection through JSTOR’s Data for Research program, but that’s not what he did. Or this howler: “It’s like trying to put someone in jail for allegedly checking too many books out of the library.” No, it isn’t, and even a cursory reading of the indictment reveals why. On the anti-Swartz side, the district attorney says things like “Stealing is stealing whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data or dollars.” If you can’t see a difference between, say, posting one of your articles on your website and lifting a neighbor’s stereo, well then I don’t know what. There’s lots of hyperbole going on on both sides.

Here’s my view: Insofar as his intentions were to further the goals of proponents of open access (and no one is more of a proponent than I), the techniques he chose to employ were, to quote Dennis Blair, “not moral, legal, or effective.”

If the claims in the indictment are true, his actions certainly were not legal. The simple act of downloading the articles en masse was undoubtedly a gross violation of the JSTOR terms and conditions of use, which would have been incorporated into the agreement Swartz had entered into as a guest user of the MIT network. Then there is the breaking and entering, the denial of service attack on JSTOR shutting down its servers, the closing of MIT access to JSTOR. The indictment is itself a compendium of the illegalities that Swartz is alleged to have committed.

One could try to make an argument that, though illegal, the acts were justified on moral grounds as an act of civil disobedience, as Swartz says in his manifesto. “There is no justice in following unjust laws. It’s time to come into the light and, in the grand tradition of civil disobedience, declare our opposition to this private theft of public culture.” If this was his intention, he certainly made an odd choice of target. JSTOR is not itself a publisher “blinded by greed”, or a publisher of any sort. It merely aggregates material published by others. As a nonprofit organization founded by academics and supported by foundations, its mission has been to “vastly improve access to scholarly papers”, by providing online access to articles previously unavailable, and at subscription rates that are extraordinarily economical. It has in fact made good on that mission, for which I and many other OA proponents strongly support it. This is the exemplar of Swartz’s villains, his “[l]arge corporations … blinded by greed”? God knows there’s plenty of greed to go around in large corporations, including large commercial publishing houses running 30% profit margins, but you won’t find it at JSTOR. As a side effect of Swartz’s activities, large portions of the MIT community were denied access to JSTOR for several days as JSTOR blocked the MIT IP address block in an attempt to shut Swartz’s downloads down, and JSTOR users worldwide may have been affected by Swartz’s bringing down several JSTOR servers. In all, his activities reduced access to the very articles he hoped to open, vitiating his moral imperative. And if it is “time to come into the light”, why the concerted active measures to cover his tracks (using the MIT network instead of the access he had through his Harvard library privileges, obscuring his face when entering the networking closet, and the like)?

Finally, and most importantly, this kind of action is ineffective. As Peter Suber predicted in a trenchant post that we can now see as prescient, it merely has the effect of tying the legitimate, sensible, economically rational, and academically preferable approach of open access to memes of copyright violation, illegality, and naiveté. There are already sufficient attempts to inappropriately perform this kind of tying; we needn’t provide further ammunition. Unfortunate but completely predictable statements like “It is disappointing to see advocates of OA treat this person as some kind of hero.” tar those who pursue open access with the immorality and illegality that self-proclaimed guerrillas exhibit. In so doing, guerrilla OA is not only ineffective, but counterproductive.

I believe, as I expect Aaron Swartz does, that we need an editorially sound, economically sustainable, and openly accessible scholarly communication system. We certainly do not have that now. But moving to such a system requires thoughtful efforts, not guerilla stunts.