Introductory Essay

Posted May 5th, 2014 byCategories: Uncategorized

True Islamic Worship Meets Culture, Society, and Nationalism

Islam, in its literal meaning, refers to submission to Allah, and a Muslim is one who submits to Allah. By these broad definitions, well-known Jewish and Christian figures like Abraham, Moses, and Jesus qualify as Muslims; indeed, they are deemed as prophets in Islam. Such understanding of the words “Islam” and “Muslim” highlight submission as the principal evidence of an individual’s encounter with the divine. Submission comes down to showing gratitude to Allah, the Creator, and worshiping Him while one is on earth. Worship, to the Muslim, is two-pronged: it is toward Allah (that is, ibadat), and it is toward fellow mankind (that is, muamalat). A good Muslim, therefore, submits to Allah by practicing the devotional life prescribed by the Qur’an and the hadiths (these are records of Prophet Muhammad’s sayings and customs). Such devotional life involves elements that are directly set toward pleasing Allah and those that are set toward one’s social responsibilities. Since devotional life is based on exegesis of the Qur’an and the hadith, and exegesis is markedly influenced by culture, Islamic worship is noticeably subjected to the social and cultural contexts in which it is practiced. Further, Islamic worship comes into very frequent interaction with nationalism and culture, sometimes resulting in varying manifestations of Muslims’ devotional lives. My blog posts and creative works explore the influence of cultural and social contexts on the expression of “true” Islamic worship.

Islam started with the supposed revelation of the Holy Qur’an to Prophet Muhammad by the Angel Gabriel in the 7th century. From the angel’s first command iqra, urging Muhammad to recite after him, to the end of the twenty-three years long revelation of the sacred text, the aural, the oral, and the written experiences of the Qur’an have featured prominently in Muslims’ devotions. Children born to Muslim guardian(s) encounter the revelation very early in their upbringing. Ziauddin Sardar, author of Reading the Qur’an: the Contemporary Relevance of the Sacred Text of Islam, recalls being introduced to the Qur’an on his mother’s lap at age six, much later than many Muslim children have this experience (3). Thus, from childhood the Muslim is taught to revere the Qur’an, experience the text by both reading and listening, and to devote himself or herself to the life prescribed by the text. A “good” Muslim, as one who truly submits to Allah and observes “true” Islamic worship, makes the Qur’an a very regular fixture in his or her life. This may take the form of reading the text or listening to a recitation of the text. There is a particular emphasis on the aural experience of the text since it more closely resembles Muhammad’s experience of receiving the revelation. Indeed, when the Qur’an was first codified as a written text, reciters were sent in accompaniment with the text to ensure that Muslims had access to both the aural and written experiences.

Such emphasis on the aural experience of Islam’s sacred text naturally resulted in later discourses on how to most appropriately recite the text. Interpreting hadith records, the well-known al-Ghazali, in his The Recitation and Interpretation of the Qur’an: Al Ghazali’s Theory, identifies ten rules that may govern the correct way for a “good” Muslim to recite the Qur’an as an act of worship (34-55). These rules are captured in the poem in the second blog post, and they regulate the pace of recitation, the posture of the reciter, and the manipulation of the reciter’s voice. These external conditions on Qur’an recitation as “true” worship, however, take different forms when Muslims’ devotional lives meet with different socio-political and cultural contexts. Scholar Anne K. Rasmussen, in The Qur’an in Indonesian Public Life: the Public Project of Musical Oratory, notes that in Indonesia, unlike elsewhere on the globe, women are allowed to participate in public recitation of the Qur’an (30). Thus, an external condition that public recitation of Qur’an remains a male’s privilege is not upheld in the Indonesian community, where the usual concern about female reciters’ voices seducing male listeners does not prevail. Gender as a factor in Qur’an recitation is only one way in which Muslim devotional life meets a cultural context and is shaped by that context.

Among the Bertis of Sudan, the place of the Qur’an in Muslim devotional life is augmented by the practice of drinking erasures of Qur’an verses and lists of the names of Allah as a form of medication (El-Tom 415). This practice, though not unique to the Bertis, is arguably a product of the intersection between Islamic devotional life and orthodox pre-Islamic religious practices of the indigenous people. Abdullahi Osman El-Tom reports that about a tenth of the Berti populace train to become fakis, people who have supposedly memorized the entire Qur’an. The fakis are the figures who are endowed with the privilege to write Qur’an verses and the names of Allah as medicines for the people (415). Thus, among the Bertis the writing of the Qur’an and the names of Allah as worship assumes what is very likely a pre-existing cultural construct of treating a sacred text as a means for healing. The first blog post captures this cultural practice. The image, entitled “Once a Student of the Qur’an, Now a Master of the Text and a Healer by it too,” depicts a trained faki at his desk with a Qur’an and a concoction presumably made from washing of Qur’an verses. The concoction is to be administered to the ailing child in his mother’s arm. The image reminds its viewers of the influence of culture on Islamic tradition and practice in a Muslim community. Together with the previously discussed impact culture has on gender as a factor in public Qur’an recitation, the use of Qur’an verses as medicine in Sudan exemplifies the different expressions of “true” Muslim worship in different cultures.

Poetry as a form of “true” worship is yet another manifestation of Islamic devotional life that is very much influenced by cultural context. Islam, at its inception, came into conflict with poetry as an art form used in religious expression. The polytheistic society within which Muhammad was emerging as a religious figure used poetry as a common expression of its religious piety, and the Prophet was neither fond of the society’s polytheism nor its use of poetry in religious expression. But, this sentiment changed later in Muhammad’s lifetime when a previous dissentient, the poet K’ab ibn Zuhayr, wrote the ode Banat Su’ad in honor of the Prophet. Muhammad welcomed this poem, paving way for a continued practice of using poetry as a form worship in Islam. This evolution of Muhammad’s relationship with the Arabian poets is in itself an example of culture shaping Islamic devotional life when the two have intersected. Later Muslims have continued to use poetry in worship. Al-Busiri’s ode and the story of the Prophet acknowledging the poem in a dream and subsequently healing Busiri of paralysis are well-known in Muslim circles. Indeed, some Muslims copy the ode with added prayer requests as an expression of Islamic piety. Poetry in Islam is, however, not just a product of the Arabic culture in which Islam was birthed; it is also frequently shaped by the cultural context in which Islam is practiced. Ali Asani in his chapter, “In Praise of Muhammad: Sindhi and Urdu Poems,” recognizes that the Sindhi poems, which often celebrate Muhammad’s birth, mimic native poetic forms like wai and kafi (161). My second blog post follows in this theme of poetry in Islam; it is a poem that succinctly covers all ten external rules postulated by Al-Ghazali to govern Qur’an recitation.

Arguably, no expression of Islam most clearly demonstrates this use of poetry in devotion as is done by Sufism. Sufism – practiced by both Sunni and Shi’a Muslims – is founded on the belief that creation, since the day of alast, seeks to be united with its Creator again, and this unity can only be attained through overcoming one’s ego (that is, nefs). Sufi practices differ across different Sufi orders, but they often include whirling dances, qawwalis, and poetry. Ghazals are Sufi poems filled with sentiments of longing for a lover, much like the Sufi teaching that creation longs for Allah. My fourth blog post, though not an Urdu ghazal, is a reflection on a classic Sufi poem, Farid Attar’s The Conference of the Birds. In this epic, Attar explores the themes of denying one’s ego and pleasures and pursuing one’s Creator – two themes which are prominent in Sufi thought and devotional expression (35-51). The birds, under the inspiration and leadership of the mythical hoopoe, chose to renounce their pleasures – symbolic of humans’ egos – in order to be united with the legendary Simorgh, representative of Allah in Sufism. The practice of Sufism and the eminence of poetry in this expression of Islamic devotional life are captured in my fourth blog post, a cardboard cut-out of a bird standing on a mount of clay dough. The beautifully colored feathers of the bird, like the affections of the birds in Attar’s work and the nefs of humans, may serve as a hindrance to the bird’s pursuit of being unified with tis Creator. The cardboard cutout bird must therefore learn to detach itself from its beauty and pride if it is to be united with its Creator. The clay dough, being an earthly and perishable material, is symbolic of the sharia which is, to the Sufis, only an external manifestation of Islamic religious piety. Thus, sharia is a mount from which a Muslim launches to pursue the more spiritual manifestation of Islam. In essence, the place of poetry in Islam, and especially Sufism, is a result of an evolutionary process that was necessitated by the intersection between Islamic devotional manifestations and the Arabic culture in which the religion first appeared.

In Complaint and Answer, Muhammad Iqbal employs poetry as a mode of dialogue with the divine. Interestingly, this use of poetry is so well accepted by the divine that, even though the poet’s complaint can be deemed disrespectful toward Allah, heaven welcomes it. In the answer, Allah tells of the magic of poetry, poetry’s “power to soar on high,” and poetry’s holy origin (Iqbal 37). In using poetry as a form of prayer, Iqbal complains to Allah about the decline in the earthly success of Muslims (3-33). This decline, according to the poet, has come on the back of continued devoutness of Muslims; in effect, Allah had unfairly forsaken Muslims. The poet’s view of the seeming collapse of Islamic civilization is contained in the leftmost heart of my sixth blog post, a painting. That heart is white – much like the impeccable piety of the Muslims on whose behalf Iqbal complains – and it is pierced by a black arrow, representing Allah’s unjustified forsaking of Muslims. Allah chooses to respond to Iqbal’s complaint using poetry, a product of culture that is eminent in Islamic expression of devotion. Allah justifies the seeming neglect of the Muslims by calling to mind the corrosion of Islamic piety. Allah reminds Muslims of the devout fathers of the faith, mentioning such names as Ali, Uthman and Ghazali. More interesting, though, is Allah’s complaint that the Muslims have embraced the corrupting religions of other cultures; they have been lured by India’s idols, and “education and refinement” have brought them to accept idolatry (Iqbal 59). That is, to Allah, social and cultural contexts like education and other existing religions in India have corrupted “true” Islamic worship when devotion and culture have met. The rightmost heart of my painting in the sixth blog post captures Allah’s perspective on Iqbal’s complaint: the Muslims have a corrupted and darkened heart that has been pierced by Allah’s just judgment, represented by the white arrow.

Hitherto, we have observed intersections between “true” Muslim worship and cultural and social contexts. Much of this discourse – gender role in public Qur’an recitation, drinking washings of Qur’an verses, and poetry as a product of culture and a common fixture in Islamic devotion – has focused on ibadat, worship toward Allah. But, Islamic devotional life has a second leg, muamalat, which is social responsibility as worship. As one may expect, social responsibility as a dimension of religious piety comes into frequent intersections with social and cultural contexts, and these contexts may influence what becomes accepted as “true” Muslim worship. Now, we turn to look at two examples of these intersections: welfare of the needy in society and loyalty toward the nation-state.

The pillars of Islam, though varying between Sunni and Shi’a Muslims, include the zakat, a responsibility toward all Muslims to be charitable to those who are needy in their societies. The intentions that donors carry when they fulfill zakat as part of manifesting Islamic piety have been prominent in many discourses. Senegalese author Aminata Sow Fall’s The Beggars’ Strike explores this discourse. In this story, the wealthy in Senegal had contemptuously approached the needy and given alms only as means of asking for more favor and wealth from Allah. The beggars, in response to the contempt, took leave of the city’s streets. A bureaucrat, with an instruction from a marabout, sought to show charity to the beggars, but the absence of the beggars on the streets resulted in the bureaucrat’s inability to observe his social responsibility. Consequently the bureaucrat failed on his aspiration for a political position. This essay will fail to resolve the conflict posited by Aminata’s novel, but we may consider a similar phenomenon that plays out in the discourse over the construction of mosques (that is, masjids). There remains the question: how much of resources should be channeled into construction of Muslim worship sites at the expense of directing these resources toward catering for society’s needy ones? The pencil sketch in my third blog post inflates this question by showing a beggar in front of a beautifully ornamented masjid. It may be supposed that this beggar has begged in front of the mosque for a long time, but his needs remain largely unmet because resources are instead used in maintaining the decoration of the mosque. Here, the context of social responsibility is poorly encompassed in Islamic piety. But, one can easily imagine instances when social enterprises like community centers in mosques have greatly enhanced the livelihood of members of a society.

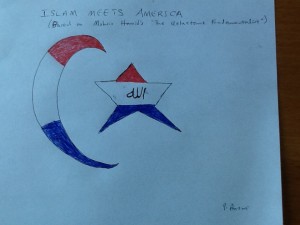

In post-9/11 United States, the authenticity of Islamic devotional life has often been questioned, mostly by Americans who associate terrorism with jihad and Islam at large. Much of this questioning has found Muslim-Americans often with the responsibility to prove that their religion does not imply a cessation of their loyalty to the nation. Changez, the protagonist in Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist, though not-American, faced this conundrum in the wake of the bombing of the World Trade Center. For Changez, as for many Muslims in America, the situation that played out during the heightened socio-political struggle shortly after the tragedy resulted in depreciated appreciation for the United States. Such appearances like the hijab for women and the beards for men unfortunately became visible markers for “Arabs,” some of whom were assaulted by some Americans. Thus, in the midst of the political conflict, America encountered a meeting of Islamic worship expressions and a socio-political context of nationalism and loyalty to a nation-state. This intersection of “true” Islamic worship, arguably evidenced by the wearing of the hijab or the beard, and nationalism are explored by my fifth blog post. The pen-sketched image in the post shows a ubiquitous symbol of Islam, the star and crescent moon, colored in red, white, and blue – colors associated with the Unites States’ national flag. This depiction calls to question again whether or not one can demonstrate Islamic piety and yet remain loyal and true to a nation, particularly a non-Islamic one like the United States.

While adherents to a religious tradition may contend that the elements involved in their expression of religious piety are of divine and unbiasedly true origins, they will find it very challenging to divorce the implementation of these elements from cultural, social and political contexts. This remains especially true of Islamic devotional life. Exegesis of the Qur’an and the hadiths are influenced by social and cultural contexts. In Indonesia, for example, women are allowed to partake in public recitation of the Qur’an due to social acceptableness, but in much of the global Islamic community only men enjoy the privilege to recite the Qur’an publicly. A pre-existing culture very likely influenced the practice of using washings of Qur’an verses as medicine among Sudan’s Bertis. Similarly, poetry in Islam was arguably a product of devotion meeting an Arabic religious practice in the early years of Islam. Socio-economic factors remain strong features in discourses on zakat and welfare of the needy in Muslim communities, while heightened socio-political conflicts in post-9/11 America unfortunately sometimes constructed devotional expressions like the wearing of hijab or beard as markers of America’s enemies. These are only a sample of manifestations in which true Islamic worship meets society, culture, and nationalism, and my blog posts investigate such manifestations.

Works cited

Asani, Ali. “In Praise of Muhammad: Sindhu and Urdu Poems.” Religions of India in Practice. Ed. Donald S. Lopez. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1995. 159-86. Print.

El-Tom, Abdullahi Osman. “Drinking the Koran: The Meaning of Koranic Verses in Berti Erasure.” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 55.4 (1985): 414. Print.

Fall, Aminata S. The Beggars’ Strike. Trans. Dorothy S. Blair. London: Longman, 1981. Print.

Ghazzālī. The Recitation and Interpretation of the Qurʼān: Al-Ghazālī’s Theory. Trans. Muhammad Abul Quasem. Bangi, Malaysia: M.A. Quasem, 1979. Print.

Hamid, Mohsin. The Reluctant Fundamentalist. Orlando: Harcourt, 2007. Print.

Iqbal, Muhammad. Complaint and Answer: Shikwa and Jawab-i-shikwa. Trans. A. J. Arberry. Lahore: Sh. Muhammad Ashraf, 1955. Print.

Rasmussen, Anne K. “The Qur’ân in Indonesian Daily Life: The Public Project of Musical Oratory”. Ethnomusicology 45.1 (2001): 30-57. JSTOR. Web. 02 May 2014.

Sardar, Ziauddin. Reading the Qur’an: The Contemporary Relevance of the Sacred Text of Islam. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011. Print.

Recent Comments