Introductory Essay

This class has forced me to ask two questions throughout the semester: “Whose Islam?” and “How do you know what you know about Islam?” Before taking this class, most of what I knew about Islam was through the lens of the Islamic Revolution. I knew very little about the Islam of artists and poets. Islam – specifically, Shia Islam – was always presented to me by various books and by my own conservative Iranian family and friends as an ideology of resistance, defined by its ability to mobilize the people in opposition to tyrants. Art did not have a primary, or even very significant, role in my understanding of the religion. Most of my blog posts explore this relationship between art and politics, and how artists’ individual interpretations of Islam affect the message they send. In this way, my posts also herald back to the cultural studies approach by emphasizing historical and political contexts. But as I will describe below, the class’s focus on the arts as a lens to view Islam as well as its hands-on approach also allowed me to learn several surprising aspects about the Islamic religious tradition that I would not have otherwise recognized if I had been limited only to writing essays.

I began the semester with this focus on the political aspects of Islam. My response for week one has to do with the varying interpretations of Islam and the cultural studies approach. I liked these questions of “how to do know what you know” and “whose Islam,” both of which I quickly realized complicate the view of Islam as a monolithic entity – a concept that I think is one of the foundations of this course and that would be the stepping stone for my other creative responses. In the past, I have definitely found myself saying things like “According to Islam…” or “It’s against Islam to do x, y, or z.” Only rarely did I ask myself “whose” Islam, which leads one to recognize not a monolithic faith but instead how people in different cultures interpret Islam. This led me to ask what it means to be an American Muslim – how my Muslim family members in America interpret their faith versus how my more conservative family members in Iran interpret theirs. The chapters from Professor Asani’s book underscored several relevant points made in lecture, and that are important concepts for the course overall: that religion varies greatly across cultures, that “American Islam” is in many ways its own unique force, and that regimes have often used religion to legitimatize their rule. To reflect the importance of the cultural studies approach this week, I created an American flag with the shahadah replacing the fifty stars and commented that the way Islam would be practiced in a Muslim-majority America would probably differ greatly from other Muslim-majority countries due to unique aspects of “American” culture. In other words, the cultural studies approach would force us to recognize that just because the citizens of these countries share reverence for the same sacred text does not mean that the way they practice their religion would be at all similar.

Three other assignments this semester – the calligraphy project and my responses for week two and week nine – gave me an overall new appreciation for calligraphy and exemplified how the hands-on approach in this class opened new doors that traditional assignments (such as essays) would not have been able to do. For week two, I drew an iceberg with the bottom three-fourths submerged in water. It was meant to symbolize the ease with which people can cherry-pick verses from the Qur’an to support certain political beliefs. The part of the iceberg that sticks out of the water is comprised of a Qur’anic verse that is commonly taken of out of context (and that was mentioned in the Zia Sardar reading as such): “We will put terror into the hearts of the unbelievers. They serve gods for whom no sanction has been revealed. Hell shall be their home.” It is easy to focus on such a verse by itself, and many people do. What is more difficult – as this class requires us to do – is to look beyond what the text itself says and look instead to historical context and how Muslims actually live and interpret the text in different times and places. As I would in my week nine response, I also learned a few unexpected things in the process of making my response. Despite using the same script, there are small but importance important differences between Persian and Arabic handwriting (like how to write the letter he – ه – when it is the last letter in a word). This was my first time writing out sentences in Arabic, so it was the first time I realized how many subtle differences there are between the two scripts.

For my week nine response, I departed somewhat from exploring the link between art and politics to copy out one of my favorite sections from a ghazal by Hafez. I surrounded the section with four symbols that are found in almost every Persian ghazal – wine, love, the moon, and a rose (the last two often referring to the beauty of the beloved). This class was the first time I was exposed to the viewpoint that the poetry of Hafez has been inappropriately interpreted as unabashedly hedonistic due to Hafez’s general obsession with wine and the beloved. Reading Elizabeth Gray’s book taught me the potential for wine and the beloved to be metaphors for paradise and God, which changes my entire interpretation of Hafez’s poetry. Of course, the introduction to Gray’s book is correct to say that every Persian has a unique relationship with Hafez’s poetry, interpreted based on his or her own experiences and beliefs. However, it would be wrong to conclude that his frequent use of wine and the beloved in his poetry is solely metaphorical; wine had a common, if not uncontroversial, presence in royal courts, and poetry praising real (often male) beloveds was common throughout Persian and Arabic poetry. But it would also be wrong to conclude that every reference to wine and the beloved is not a mystical one.

While it was interesting for me to explore in an academic sense the symbols and methods that tie all ghazals together, the real adventure for me that week was copying out the ghazal itself. To do so, I used a calligraphy pen that my mother had bought for me during my freshman year, when I first began to learn the Arabic-Persian script. This was my first time actually using the pen. Writing the selection of the ghazal was so much more frustrating and difficult than I ever imagined; I went through at least fifteen pieces of paper until I was able to produce that section of the ghazal with somewhat acceptable quality (or at least without it looking too obviously ugly). I always recognized the beauty of calligraphy – and there are several beautiful works of calligraphy in my house – but now I am a little in awe as well in ways that I wasn’t before doing this week’s response. The last time I was in Iran, I remember thinking dismissively about why there were so many schools devoted exclusively to calligraphy. I did not fully understand or appreciate the importance of calligraphy in any Islamic tradition. In other words, I recognized the beauty of calligraphy, but I rarely thought about the skill and hours of labor behind every work of calligraphic art.

My week five response returned more blatantly to my fascination with art and politics. This week was concerned with the fusion of politics with art through the taziyeh, the Iranian “passion-play” about the martyrdom of Imam Hossein at Karbala. I had never put much thought into how malleable that story could be for modern-day political ends. I was also surprised that week about an aspect of Shiism that I always felt but never put into words – namely, the ethical duality between good and evil, personified in the figures of Hossein and Yazid at Karbala. While searching for a painting of Yazid online to add to his side of my yin-yang art collage for that week, I was surprised to find several propaganda posters proclaiming Yazid to be America or, in one case, showing a man clearly dressed in all-red as Yazid standing next to Barack Obama. It would be impossible to understand such art if one didn’t also understand the religious and political context of the day.

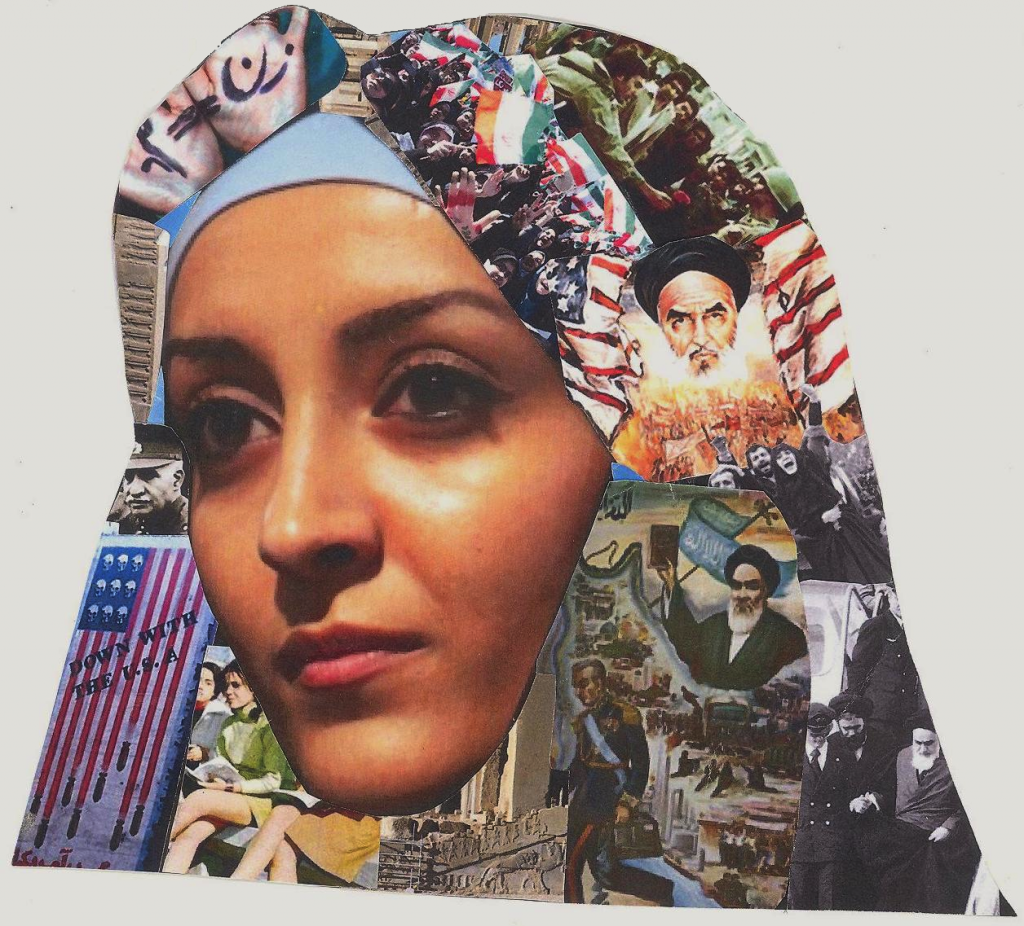

My week eleven response was another example of how I wanted to explore how art has been used in Iranian politics specifically. I found the several readings this week on Iran and the Islamic Revolution to be problematic in the same way that many books and articles on the Middle East are problematic: they use women’s clothing as a measuring stick for the shifting political values of a country. For many women I know, the choice to wear the hijab (or some form of it) is an intensely personal decision, and these veiled women have diverse political views. To say, as the readings this week did, that we can tell the Islamic Revolution brought to power a “conservative” government because many women were forced to cover their hair – or that Iranians are increasingly unsupportive of the Islamic Republic because their headscarves are far enough back to show some hair – seemed like an oversimplification compared to what Islam and Islamic dress might mean to individual Iranian women. (The question is, again, “Whose Islam?”) To show how wearing a chador or any type of veil can be interpreted with so much political force, I made another collage by placing important moments from Iranian history (including a few famous posters from the Islamic Revolution shown in one of the readings) within a woman’s chador.

Although I wanted to learn as much as I could about Iranian or Persian art throughout the course, I also tried to step outside my comfort zone by focusing several of my creative responses on art from Muslim cultures other than the ones in Iran. To this end, I chose to do my week twelve response on Rokeya Hossain’s short story “Sultana’s Dream” instead of on the graphic novel Persepolis by Marjane Satrap (which I had already read for other courses). Of course, Royeka Hossain’s emphasis on the importance of education was powerful to me as a student, so I focused on both the specific problems facing women in her time (namely, isolation) as well as her general emphasis on the importance of scientific pursuits when taking the photograph of my roommate surrounded by her many different biology and physics textbooks. The inevitably political nature of Royeka Hossain’s demands – that women have a right to be educated and to leave the private sphere in this sense – was inspiring to me because her feminist demands were still rooted in Islam. In other words, her Islam criticizes everything that my photograph for this week conveys: the complete isolation of women and their untapped scientific potential (and their often-denied right to an education).

Ultimately, some of the most enriching parts of this course came unexpectedly through the hands-on application of concepts and these creative responses. Making the creative responses clarified many political concepts in my mind – the ethnical dualism in Shia Islam, for example – but more often than not, I was surprised through making the art itself. I gained a new appreciation for the art of calligraphy, for example, and realized that Qur’anic Arabic feels very, very different from Persian despite using the same script. Most of all, I learned in this course that there is no one Islam, and the incredible diversity in the arts exemplifies the diversity of this faith that stretches across every country in every continent.