An Introduction

ø

For the Love of God and His Prophet: Religion, Literature, and the Arts in Muslim Cultures contributed in a profound way to my understanding of Islam and its various, localized manifestations. Professor Asani made a concerted and deeply conscientious pedagogical choice to teach about Islam through a cultural studies approach; in my own study throughout the course, it became apparent rapidly that this was the most balanced, fair, and insightful way to do so. Indeed, if there is a single lesson to be reduced from the class, I think it would be, “which Islam?” As Professor Asani writes, this is to say that it is a deep, and often problematic, fallacy to cite “Islam” as “saying” anything.

Religion is experienced in a way that is multivalent, and an individual’s perception and practice of a religion is mediated by his or her more general spatio-temporality and his or her more specific age, gender, race, and sexual orientation. Often, for better or worse, discrepencies exist between Islam as it is written in the Qur’an and the Hadith and Islam as it is applied practically. These discrepencies exist before one even considers the possible contradictions within the Qur’an and Hadith themselves or the infinite manner by which both can be interpreted. The fact that there is no “one Islam” agreed upon by all Muslims exposes the need for scholars and laypeople alike to deploy more ethnographic methods in understanding how a religious text plays out in highly particular ways, mediated by local cultures and traditions.

This theme of cultural particularity is one that I think weaves a common threat throughout my blog posts. In some ways, my understanding of Islam prior to taking this course had been predominantly shaped through experiences of living and of visiting places. One of my first blog posts, for instance, speaks of the profound experience of living in a homestay in a Muslim subvillage in northern Tanzania during the summer two years ago, coinciding with Ramadan. Interacting with the Imam to plan health lessons in conjunction with the NGO I was working for, modifying my lesson plans to be culturally sensitive and practical, and breaking fast during Ramadan with hot porridge sitting outside on stools or buckets with my home stay mama and sisters are all ways by which I first understood an Islam in any substantial way.

Serendipitously enough, last summer I was again working for the same NGO in a different ward in Tanzania. My flight at the end of the summer had a layover in Doha, Qatar. We landed at 7:00 pm and my flight to the US didn’t leave until mid-morning the next day. I had perused a pamphlet about attractions in Doha on Qatar Airways on the flight from Tanzania, and was thrilled to learn that the Museum of Islamic Art would be open from 8:00 pm until midnight – special Ramadan hours. I was in the stunning building by 8:00 and left at midnight having absorbed Qur’anic manuscripts, gorgeous calligraphy, incense burners, and Persian rugs. Wandering the night market, amidst the smoke of hookah and the smell of Arabic coffee, I bought an embroidered taqiyah by which to remember my time. My understanding of an Islam grew a bit more, again outside of the realm of the didactic.

Just recently, I came to understand an Islam through the lens of Israel and Palestine. Ascending to the Dome of the Rock at sunrise, seeing beautiful Arabic calligraphy on the old walls of Jerusalem, and visiting Ramallah added to my small but growing reperatoire of what Islam means in different places – the commonalities and the stark differences.

As someone pursuing a secondary field in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations: Modern Middle Eastern Studies, I have had opportunities to learn about Islam, usually indirectly through regional studies, in a more didactic fashion. I’m currently enrolled in a class on Culture and Society in Contemporary Iranian, which partially explains my special interest in the Iranian Revolution and the ways in which Shiism was invoked by Ayatollah Khomeini and continues to be invoked by the current regime. In that class I was exposed to a range of ways that a particular brand of Islam is used for everything from justification of sex change operations to the illegality of homosexuality to the existence of the regime. This, of course, provides insight into an Islam widely regarded to be a perversion of “true Islam,” whatever the values therein may entail.

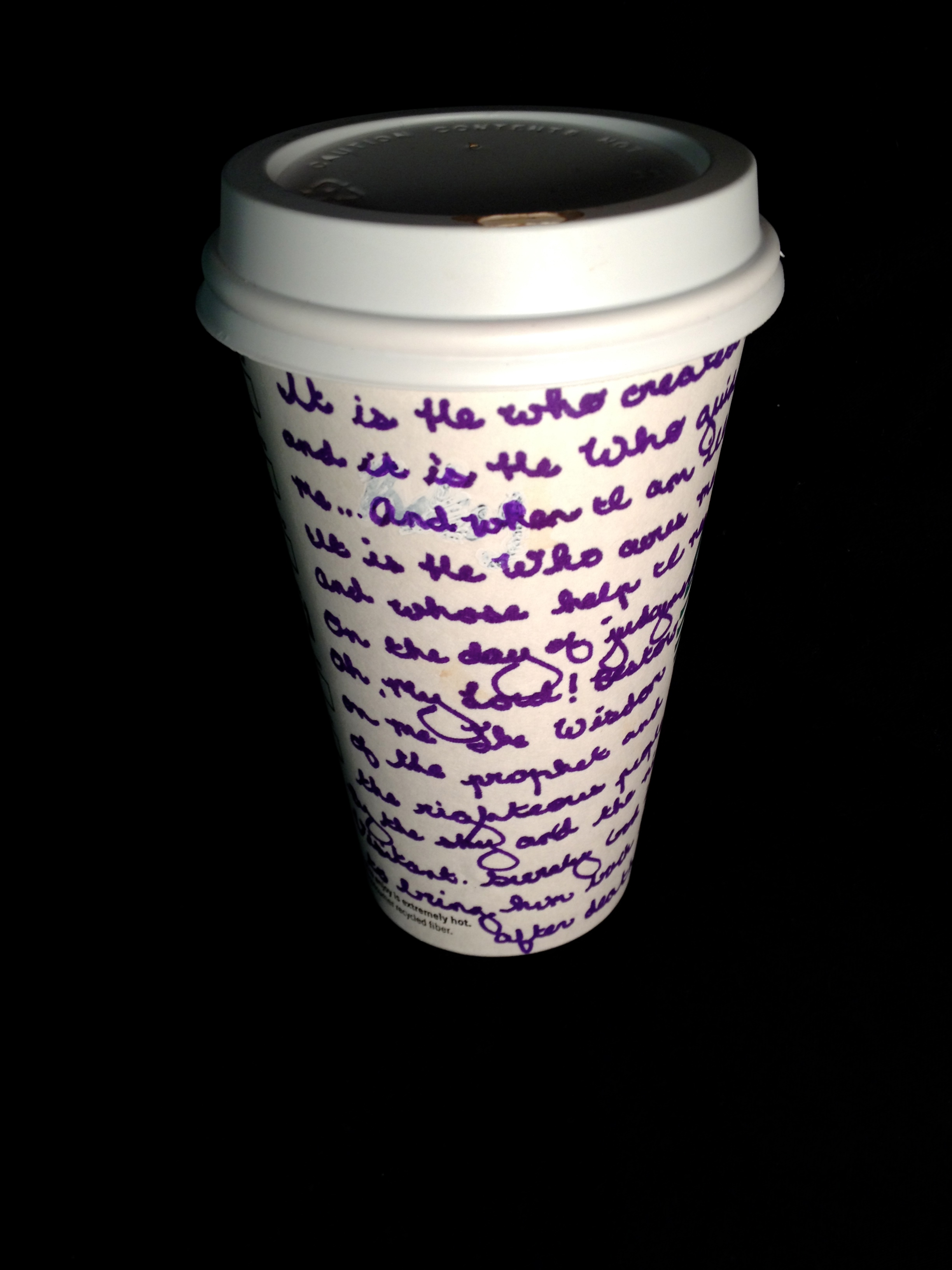

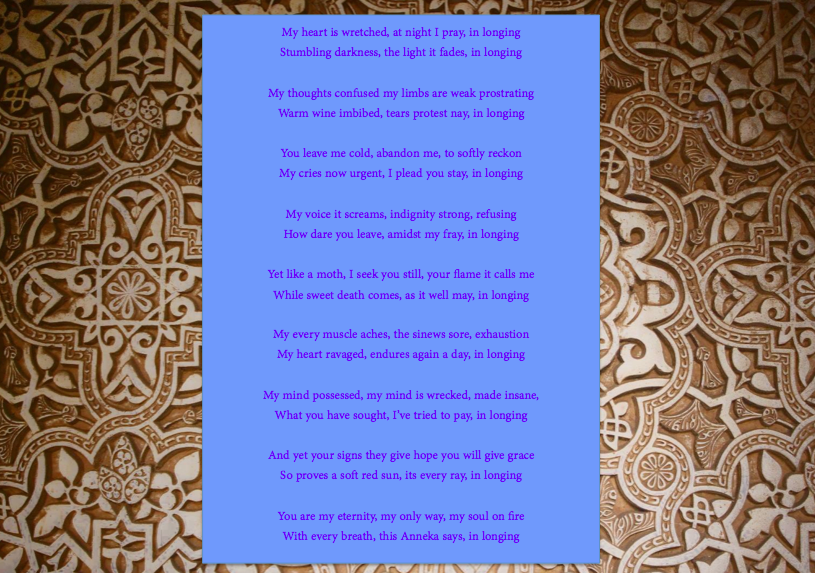

Finally, I really enjoyed learning from Professor Asani’s class about the arts in Muslim cultures. Exploring everything from drum ceremonies in Senegal to Persian ghazals to Sufi mystic chanting underscored the deeply diverse and beautiful ways by which faith and culture are expressed. I tried to contribute in my own small way to this expression in my blog with photo exhibits, my ghazal, a calligraphy project, a diptych, and my “Qur’an Cup” piece. I hope you enjoy!

Very Best,

KAM