I began this blog hoping to meditate on the centrality of the Qur’an to Islam as well as on my own experiences approaching this text by learning more about different religious practices, literature, and the arts in Muslim cultures. However, over the last thirteen weeks of reading, lecture, and discussion, I found myself fascinated most by the incredibly diverse and divisive visual expressions of Islam across geographic and historical contexts. As well as representing some of the many ways of expressing community and devotion, visual objects participate in an often heated debate over what it means to be a Muslim and a person. To what extent should Islamic beliefs and practices blend with other or earlier systems of belief and worship? How should the divine be depicted? How should the community be understood and organized, especially with respect to the role of women?

In addition to observing and discussing some of these visual debates, creating this blog provided me with the opportunity to think and respond by creating my own artwork: a map, a painting, a drawing, folded figures, a collage, and a sculpture. I chose to make only visual works and not to construct songs or videos because I feel that this mode of creation engages me most with my thoughts. Learning visually provided an interesting and unique lens to think about the Qur’an, God, and faith in lives around the world as well as in my own life.

Professor Asani began our class with an introduction to the diversity of Islam, showing the incredibly wide and varied distribution of Muslims around the world, as well as verses of the Qur’an emphasizing diverse experiences of islam, which literally means simply submission. Though initially I identified Islam strongly with its area of origin, the Middle East, the majority of Muslims today live in South Asia, and Muslims worship in countries around the world. My first response for the blog explores a little more of this fascinating diversity, showing the geographic extent of Islam and linking to images and articles focusing on each particular country. Though cartography can be considered a science as well as an art, I felt that this more straightforward creation echoed my own initial point of entry to learning about Islam.

In addition to the variation within Islam, I found the uniting threads between Islam and other monotheistic- as well as polytheistic- faiths both surprising and interesting. We discussed the Qur’an’s integration of and respect for Judaism- “Abraham was not a Jew or Christian but an upright man who had submitted (musliman)” (Qur’an 3:67)- as well as for Christianity- “When Jesus found unbelief on their part he said: ‘Who will be my helpers to (do the work of ) God.’ Said the disciples: ‘We are God’s helpers: We believe in God, and do you bear witness that we are muslims (submitters)’” (Qur’an 3:52). The term ahl al kitab– people of the book- includes Muslims, Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians. Another sura emphasizes the unity of faith as well as the diversity of ways to worship and connect with the divine: “Have you not seen how to God bow down all who are in the heavens and the earth, the sun and the moon, the stars and the mountains, the trees and the beasts, and the many of mankind?” Qur’an 22:18. This verse emphasizes how all can worship in their own way, emphasizing bowing down to God instead of any particular theology or practice.

Though Muslims believe Muhammad represents God’s final messenger and the seal of the prophets, the number and diversity of prophets respected, as well as how these vary across geographic, cultural, and historical contexts, fascinated me. Accordingly, I focused my visual responses to what I was learning around these men and women. I loved the story of the mi’raj, the prophet Muhammad’s journey to the farthest mosque and ascent to the highest heaven. The Persian miniature paintings we looked at in class captured my imagination, especially in light of what I had previously assumed was a restriction on representing the human form in Islam. The reproduction of aspects of this journey in Dante’s Inferno also surprised me- the extent of movement and connection across regions and religious traditions even in the 14th century remains an aspect of historical and religious study I wish I had received more prior exposure too, particularly in light of our increasingly globalizing and connected world today, with all the affiliated benefits and issues.

How to represent a prophet, and most importantly, the prophet Muhammad? Although some Muslims resist representation of living beings on the grounds of hadith, the traditions of the prophet, explaining the creation of living forms as reserved for God alone, the Qur’an itself only condemns idolatry: “Anyone who sets up idols beside GOD, has forged a horrendous offense.” (Qur’an 4:48). Art, and figural art, is not prohibited. As with any aspect of theology, interpretations of how to depict humans and the divine vary widely across different contexts. One author we read for the course even suggests that prohibitions on figurative images developed from Jewish thinkers or Christians in opposition to the Byzantine empire (Grabar, 40). Regardless, I choose to depict the prophet Muhammad in my own depictions with a flame to mark his holiness and with his face in shadow. Because of the veneration and honor afforded to Muhammad, taking extra care to simultaneously mark him as important and to avoid making his image an idol felt important to me. I also chose to depict another important prophet with a specifically local context, Shakh Amadou Bamba, the founder of an Islamic Sufi Movement in Senegal and the Gambia. As well as being a spiritual leader, Bamba helped crystallize resistance to the French colonial regime. In this respect, Bamba reminds me of Muhammad: in addition to fostering the worship of God, both men worked for social justice. Considering how to represent Bamba also made me consider different representations of Muhammad and how each fits into a particular culture and belief system. In Senegal, images of this man and other holy figures are considered to have real power, baraka associated with divine grace. Again, I focused closely in on the prophet and left his face in shadow to try to simultaneously engage in thoughtful respect or veneration while trying to avoid idolatry, though some might consider my reproduction such.

The diversity of prophets, prophecy, and representation we discussed covered much more than visual art. I especially enjoyed learning about Sufi devotional poetry because this seemed so outside my usual experiences of expressions of religious culture. I particularly enjoyed searching through the layers of meaning in Farid ud-Din Attar’s 12th century epic poem The Conference of the Birds. The experience of reading the poem reminded me of Sufism’s tarigat, the spiritual path towards God and the truth by which a believer looks for the inner dimension of things rather than the external and laws. In addition to different artwork and practices, Islam covers a wide variety of theologies and ideas on how to approach the divine and live a good life. Inspired by the ideas of Sufi mystics, I chose not to continue my exercises of imitation and reproduction, but to produce a visual response only out of my feelings about the work. I appreciated the different perspectives, vibrancy, and elegance: accordingly, I folded bright paper birds.

My birds also engage with Islamic traditions of figurative representation, but their forms are so abstracted as to serve perhaps more as arabesque, stylized motifs like those common in Umayyad design and architecture. We discussed interpretations of these abstract forms as theological or cultural, a dilemma that seems to cover much of the artwork of the class. Nebahat Avcioglu’s essay, “Identity-as-Form: the Mosque in the West” engages further with traditions and what is considered Islamic. By building my own lumpy and impermanent mosque out of modelling clay, I tried to think about what defines holy art and a holy place for worship.

In addition to the wide diversity of worship and to the long and complex traditions of figurative representations, this blog seeks to engage with Islamic arts and literature employed for criticism and resistance. Beyond merely expressing religious and cultural values or historical and geographic context, the artist can use her work as well as its religious aspects to highlight injustice and suggest change. Rokeya Hossain’s 1905 short story “Sultana’s Dream” presents a technologically advanced imagined world where men instead of women live in complete seclusion. As well as imagining and creating a vivid world, Hossain uses her creation to emphasize the injustice of purda and suggest alternatives- technology, efficiency of work, a religion that values love and truth above all. Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel Persepolis also imagines a world, based on the Tehran before, during, and after the Iranian Revolution, and depicts that world vividly through Satrapi’s childhood eyes. Again, Satrapi’s art allows her to highlight the injustices and tragedies of the upheaval of the 1970s, in a more engaging and perhaps even more true way than facts or more straightforward narrative.

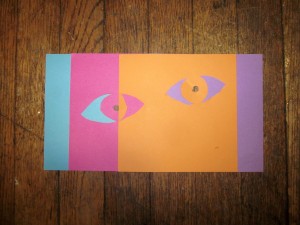

Hossain and Satrapi use art to open their readers’ eyes to another perspective. Filtered through each writer’s own historical, cultural, and personal context, the books nonetheless seem to open a window to experience and belief. The eyes I taped together also serve as a focus for the final artwork we considered this semester, Mohsin Hamid’s short novel The Reluctant Fundamentalist. The frame of the story, a conversation between the Pakistani Changez and an unnamed American visitor standing in for the reader, shows the reader alternatively the world through Changez’s eyes- and his switching eyes, as he embraces and abandons particular viewpoints and ideals- and the eyes of the unnamed American he speaks with.

What I appreciated most about this course and what I attempted to do through this blog is an attempt to look at a religious tradition very different from the one I was raised in through a range of other sets of eyes, using artwork as a lens to examine historical, cultural, and personal contexts. I hope you enjoy the rest of my blog!

Recent Comments