Friday, July 13th, 2007...10:52 am

Days 28 and 29: Paros and Antiparos

Hotel Cecil, on Athinas in Athens, could be any of a dozen hotels in twenty cities. I’ve stayed in the same little place in New York, California, Italy, and Turkey, now, I think — an pink ancient building on a main street, its elevator a wire cage that rattles and protest at any bag, or person, in excess of 50 pounds. Marble steps curving around a two-wing hall on each floor, with five floors total. Breakfast an understated but totally adequate affair. Yesterday Ashlie met me there at 9 yesterday. (Yes, 9. I know.) We proceeded on to the Acropolis and to reconnoitering Plaka and the Centre together. It was fantastic. More below.

Our first stop, or first attempted stop, as I think it’s still unclear whether we properly assayed the area, was the National Gardens. More graffiti. At least this time it was politically responsible: “AIDS KILLS” on a public bathroom. Okay. The gardens were pretty but, and here I recalled hours and days spent in botanical gardens and arboretums as a child, fairly unremarkable. It was this conclusion, though, that led me to suspect that we didn’t get to the National Gardens proper but only a nearby park or something. We tried. It was a valiant effort.

After, we made it to the travel agency to get our ferry tickets for Thursday to Paros. Our English-speaking was as popular as usual, despite our hushed tones and attempts at being as un-American as possible — and despite Ashlie’s use of Greek, which was impressive. The travel agent informed us there were only first-class tickets each way to Paros; finally she found ‘aeroplane’ seats on the way to, but for the return we were stuck paying an extra 20 euros each for first-class. We wouldn’t regret it, ultimately, after several days traipsing around the isle and its mate, Antiparos, but at the time it was a huge imposition. Also a huge imposition: paying cash, due to the failure of the agency’s computer system. We located an ATM several blocks away and withdrew euros adequate for the newly elevated estimate for the ferry tickets, booking it back in order to avoid our schedule for the day being too upset. We waited in line again, only to be scolded once we reached the head of the line — mind you, we were fully visible the entire time we waited — for having waited in line again. “I told you not to wait,” the same long-nailed agent exclaimed loudly, directly contradiction the message she had delivered just as loudly earlier as we’d scurried out to find an ATM. She’d reminded us also at that juncture, also loudly, that we had to be back within an hour or our tickets would be resold.

Onward from the agency to food. Poor Ashlie. I’m always hungry. It’s why writing these emails was never too, too difficult: I can usually remember my day by remembering my meals. In any case, I had pork souvlaki from a little café that day, surprisingly inexpensive. Probably the only meal I had in Greece for under 8 euros. We checked out the Compendium English-language bookstore next door. Not finding “The Unbearable Lightness of Being,” which a friend brought to my attention as a glaring gap in my education, I looked at the next best thing, postcards. Being unsatisfied by that selection either, we moved on to the Benaki Museum.

The truly mystifying thing at the Benaki wasn’t any Byzantine mosaic or a tryptych or any other artifact. It was a set of modern artworks haphazardly integrated among the exhibits, marked only by a little robin’s egg blue placard with a few unhelpful words on it. Among a group of 17th century costumes on manikins was a black hooded figure that seemed as though it belonged in a horror movie rather than a museum. We tried in vain to identify the figure for several minutes, thinking it might be some ritual or religious costume. Later we saw a light show superimposed on a beautiful painting of a nautical scene. A floor above, even more puzzling, there was a series of stones on metal stakes a dozen meters away from an exhibit on Greek poets. On the way out we revisited the first exhibit with one of the modern-art placards. We couldn’t tell what part of the item, a Janus bust, was modern — maybe the mirrors placed alongside it?

We emerged onto the sidewalk, into the tepid, scorching air of Athens in July, and started for the Acropolis. We strolled the Ancient Agora, appraising tourists as frequently as towers, and passed a few other structures before moving on to scale the innumerable steps to what became one of my favorites, the Areopagus, perched on a hill with a view of Athens second only to that at the Pantheon. From there you can see well enough to discern the layers of fortification in the walls surrounding the acropolis, even picking out the column drums later added. (Thanks to Ashlie, of course, as it would have been wasted on me without her adept eye and knowledge of all things classical.)

We stayed there for a bit, reading in Ash’s guide about the function of the Areopagus and its details. It was the equivalent of the Senate, and later a court dedicated to corruption and then homicide.(I draw now from a combination of the Rough Guide and Wikipedia, with the advantage of internet.) Yes, of course, the politics were my favorite part. Finally stirred from the hilltop, from thinking about the Grecian and Roman politicians who’d held for there, we slid down the slippery original stone — having eschewed the ugly, recently added steps for the ancient ones, as it’s one of the only places on the Acropolis you can still use the original steps — and headed for the frozen lemonade stand and the water closet, as Ashlie referred to it.

|

Two frozen lemonades later we resumed our trek uphill to the temple of Athena Nike, Erectheon, and Athena Parthenos. Many, many, many steps later we came to the entrance. We got to the Erechtheum, or the Erechtheion, depending on whom you ask, and it was absolutely spectacular. That’s a feat, in the shadow of the Parthenon, but then again, construction mars the Parthenon just as it obstructs the view of the Aya Sofya and a dozen other amazing sites. Historical preservation is ugly. The caryatids in the Erectheon are really beautiful. Wish we could have gotten closer. My zoom only works so well. Of course just as I was succumbing totally to its spell, a young couple slouched by and the girl said to her sulking boyfriend, “I can’t believe we paid 12 euros for this.” I wish I could claim that Ashlie translated from Greek or I from Spanish, but of course they sounded very, very American.

The Parthenon, even obscured, was beautiful. Lord Elgin’s crime became more astonishing to me, and the continued refusal of the British Museum to return the marbles (and, too, the possession of yet more statues by the Louvre) more grave. Sadly the museum was closed, probably pending the transfer of its contents to the new museum, tiny from the point of view on the hill. Ashlie told me a crane will lift the contents of the museum directly to the new one. An interesting idea. Just waiting to see how it backfires: can you imagine dropping priceless cultural treasures ten blocks onto the pavement of Athens? We went back, past the Temple of Athena Nike, and then on down to the Theater of Dionysus and the Odeon, where Ashlie saw a concert recently. It amazes me that it’s still used today. We had perhaps too much fun in the theater, trying in vain to conquer the genetic curse of un-photogenic-ness. Every time she took a photo, Ashlie swore I’d like it. And vice versa. The outcome was that my camera was filled with several hundred photos of one or both of us, at arm’s length, mid-bray. Not the most attractive, but far more valuable by the photo criteria we developed: we look happy.

|

On to the Roman Agora and the Tower of the Winds. Apparently there’s ongoing discussion or debate of how water clocks worked. Ashlie also pointed out several blocks with divots that would have been the pivots for doors. Apparently it’s a graduate-student level skill. I had nothing to offer archaeologically, instead contributing by obeying boundaries set by ropes and not stepping on important things often. Of course by that late point, it may just have been the threat of the shriek of the whistles held by the rare monitors stationed randomly throughout the Acropolis that compelled me to be so obedient. The ropes are scattered, the areas one can enter and frequent randomly defined to the untrained eye. I resented being confined at times. Ash promises that the less urban, less popular sites throughout Greece are still free for exploration and examination. Not to say that my examination is particularly informed, but only to protest being charged 6 euros only to be restricted from viewing the most interesting parts of the ruins and whistled at — in a bad way — by surly Greeks.

We stopped for coffee nearby, in view of the agora, and there I had my first freddo. I’m probably still spelling it wrong, but that’s not an inaccurate reflection of my deeper incomprehension of what the drink is. Something vaguely cappuccino-like with a layer of frothed milk. Very pretty. Really delicious. Probably terrible for me. Mm. Freddo metrios, meaning medium sweet, I think. (Ashlie is receiving this email and will inform me if this is incorrect. Hopefully.)

|

The graffiti still bothers me. Here are sites hundreds and thousands of years old surrounded by the garish slashes of paint proclaiming the dominance of one gang or another or simply offering an opinion, a name, or depicting a random icon or symbol. Even in the ruins a few stones had been marked. After the meticulously maintained and monitored sites of Turkey, the haphazard preservation and protection of these archaeological sites was alarming. Other parts of Athens, though, are startling modern and efficient. And trusting. The metro, for example, is bright and clean, and would be very easy to game. Your ticket is a slip you insert into a machine, just like in most US subways, but unlike US systems, the Athens metro machines do not block your entry. They’re just a series of mechanical stalks between which you could walk right down to the train, or into which you could easily feign inserting the metro card. And there’s no oversight that I saw. But there was also no obvious abuse of the system. Trains weren’t overly crowded; passengers weren’t raucous; and, actually, I didn’t see many or any of the homeless people who usually inhabit some public areas and transportation in cities. I didn’t see many anywhere, actually. Of course, it was summer. But still, I like to think it’s because Athens is progressive and cares for its homeless.

Ashlie and I went exploring the more contemporary parts after, with her patient explanations having extended from Areopagus to Hondas Center. At the center, we spent several hours, it seemed, examining and finally purchasing sunscreen for our isle adventure. Somehow in Greece SPF 10 is “medium” coverage. (Writing this with several days of use behind me, I can tell you that I tanned plenty with this “medium to high” coverage.) We also hit Carrefour, which was basically a Super Target with more variety. Just waiting for Target to pick up on these electronic price tags on shelves so they can change their prices more frequently and more quickly. I know it’ll be big here in Alexandria.

Although near collapse after a grueling day in tremendous heat, we scraped ourselves up, repositioned our considerably heavy, sunscreen-laden bags, and moved onward to Pangrati. Ashlie is the guru of public transportation in Athens, and she somehow navigated us to a little taverna up a confusing, steep set of steps and a sidestreep — within steps of a home that belonged to, I think I understood Ashlie correctly, George Seferis. Probably wrong, but, in any case, I enjoyed the thought that this was the case as we moved back it, hearing the clicks and bumps of dinner set up coming from the home or nearby it. Suddenly we were on a little street standing in front of a pretty little taverna lit by a series of white Christmas lights. The inside was deserted, empty even of chairs, except for the tavern’s British proprietor, propped over a large accounting device of some sort, who looked over her glasses long enough to wave Ashlie through to the back garden where people were spilling over from one table onto the next in a crowded, blissful cove surrounded by two dark apartment buildings where lines of drying wash hung along lines strung from the balconies. Wine measured by the kilo sat on every table in colorful metal containers that were, I think, called meso kilos.

|

We grabbed a small table at the mouth of the cove and settled in, watching the crowd until finally handed our menu. Nearby a badly behaved pair of children screamed for their father repeatedly, in his ear where I cannot help but believe he heard it, while he smoked indifferently. Beside us a couple sipped ouzo, her feet incongruously planted in his lap as an unrelated party of four sat only a few chairs down at the same long table. Ashlie and I ordered set of small dishes, not unlike the style of a tapas restaurant, and continued our running commentary on Greek children, couples, and the proliferation of cigarettes. We caught up a bit on US news, as I had followed it as due course in Ukraine, among other Americans desperate for discussion of Obama and Giuliani, and she’d been happily surrounded by Greek and Greeks. I found that I was enjoying gradually falling out of the loop, having not checked on US politics or news in depth since my last day in Kyiv. Eventually our waiter produced lemon beef, feta-stuffed baked peppers, and fresh vegetables with more feta along with a shared meso kilo, and we happily dug in. After, an internet café to check email for work and send out a few urgent little missives.

As we prepared to waddle back to respective roosts, we planned the next day. A very early morning, 5:45 am, for the ferry. By that point there wasn’t much point in sleeping, and I don’t think either of us did. We met and metro-ed to Piraeus the next morning with a minimum of grumbling, though, for our sleeplessness, knowing that we’d be given 5 hours onboard to catch up from the night before. Just before we boarded we stopped at a vendor whose products were, I swear, nearly identical to those of Istanbul, and grabbed two small loaves of sweet bread with raisins and nuts. The raisins were almost sandy, we commented, as we walked onboard. Two hours later I woke up to the roar of our seatmates snores and saw a very green Ashlie. The raisins had come back to haunt Ashlie, who was miserably ill from a combination of seasickness and bad bread, and, meanwhile, I was simply hungry again. There must have been some serious immune-system benefit to traveling in Nigeria and Honduras. In any case, I tried vainly to come up with something for Ashlie and failed. She requested juice. Couldn’t find juice. So I brought her back hot black tea. She thanked me politely, and I went back for some more and a bit of food for myself, having already digested the ecoli-laden bread and being hungry for salomonella or something else tasty. When I got back, she was gone. She came back, so nicely, and thanked me for the tea: it had really forced her to expel the last of the bread. A mixed compliment, really, for my nurturing abilities.

Chastened by that and the continued sawing of our seatmate’s snores, I tried to stay up a bit. I was useless and eventually gave up, a full five minutes into my attempt to be helpful, and fell back asleep. I awoke as we grumbled into port in Parikia, Paros. We grabbed our bags and rushed into the sudden massive flow of people trying to disembark the ship. It felt a bit disaster-like, and I couldn’t help looking around to reassure myself there were no life vests or inflatable rafts present. We finally shot out into the sunlight, propelled by elbows and backpacks, and Ashlie began the process of looking for a place to stay. On the isles of Greece, the process of finding a room is simple: look for a waving sign with appropriate designations, in this case, “Siroco’s Rooms,” as you spin out from the boat. Grab an offer quick, before other ferry folks, and hope it’s nice and not horrifying.

Although we were greeted at the door by a stern and dyspeptic looking woman by the very appropriate name of Priscilla, whom we would henceforth refer to as Priscilla Queen of the Desert, of terrible temprament and indeterminate European origin, our little room was terrific. For 40 euros a night we had a double with air conditioning, nice linens, a little porch, a refrigerator, and access to a pool. Ash wasn’t up for too much but humored me in venturing out to the pool, where we stayed and read for an hour. After the hour was up and Ashlie was still feeling a little better, we moseyed down to the beach. Our rooms were really convenient to Parikia proper, and so in 10 minutes we managed to find a grocery store with fresh cherries and yogurt and a little beach to settle onto for a few hours. A brief swim was enjoyable but made less so by the preponderance of rough rocks — and a mortal fear of sea urchins helpfully inculcated in me by Ashlie — and my immediate and well-thought out decision to flood my left ear with water. We fell asleep, predictably, luckily with the protection of sunscreen, and awoke around 6 or so with the sun still glaring down and my ear still full of water. I danced on one foot for a while trying to shake the water out but accomplished only offending all neighbors on the beach with my obvious American-ness.

|

We returned to the hotel and napped a bit before dinner, striking out then to the harbor, only a bit further than the beach, and to a pharmacy. And here is the point at which I must truly get enthusiastic about Greece: their pharmacies are incredible. There is nothing a Greek pharmacist cannot do. Ashlie had prepared me for this fact of life in Paros, but I was doubtful, and not particularly encouraged by the appearance of our pharmacist. He looked like what I thought a medieval apocathery must have looked like, or at least as Steve Martin dressed as the Barber of York on Saturday Night Live. He had on a tunic with a laced neck and a massive scar down one side of his face.

Ashlie went to pains to explain to him in Greek that I had water in my ear. He looked at her seriously, then turned to me and said, “So, you have water in your ear?”

I nodded pathetically, feeling like a six-year-old pouting after swim practice.

“I have solution. It will take 30 minutes to prepare.”

We skulked out. Thirty minutes of wandering later, we arrived back at the pharmacy. He uprooted himself from a table outside and disappeared behind the counter, returning with a clear bottle filled with a clear solution. (A sniff later would offer the conclusion it was probably just hydrogen peroxide.) He proffered it and a spray bottle to bring down nasal congestion, which he rightly concluded was probably not helping the issue. Ashlie shyly asked about nausea, and he turned and with the flourish of a maestro whipped out a very modern-looking nausea drug that looked oddly anachronistic in his enormous hand. A few euros later, we went to dinner, me having tzitziki, the most amazing appetizer created, and some more souvlaki, in my attempt to consume the nation’s supply before leaving for my own cuisine again. After, Ashlie promptly crashed while I attempted to coax the stubborn, high-saline water out of my ear with the use of the apothecary’s solution and a hair dryer. Several attempts into the process, I was successful and was able to myself collapse, not without again suffering a wave of sureness that I was about six years old for having been so trouble by and insistent upon resolving the water-in-the-ear crisis. But, hey, it really hurt!

The next morning we gave ourselves a little time to recover, Ashlie from her legitimate bread-and-seasickness illness and me from the harrowing experience having gotten water stuck in my ear like an idiot. Then we hopped a bus at Priscilla-Queen-of-the-Desert’s direction, which, instead of taking us to Pounda as promised, took us to Alika. It was pretty, but not Pounda, and therefore not a useful destination en route to Antiparos. Fortunately for us the bus ticket-taker was sympathetic and let us ride out our one-hour inadvertent detour free of charge, then directing us to another bus to take us to Pounda. Unfortunately, he was less intelligent than he was kind, and no sooner had we gotten off the bus than a horde of people poured in — it had changed route from Aliki to Pounda, and having gotten off the bus, we had now sacrificed our place and would have to wait 40 minutes for the next one. An hour and half after we set out, we were finally on the bus to Pounda. It arrived just as the ferry was departing, and so we hopped on and were shortly thereafter on Antiparos. The five minute ferry ride in high winds was memorable mostly for the view of the parasailers, and two intrepid windsurfers, making the most of the major-league gusts. On Antiparos a bus was waiting to take ferry arrivals to the caves, which have, apparently, no more formal name than The Caves on Antiparos, and we jostled up to the caves promptly.

|

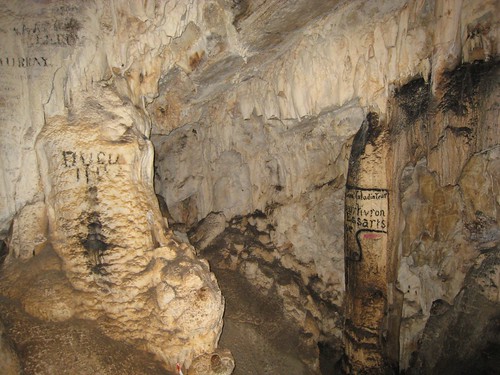

An hour spent exploring the cave did not yield the promised name of Lord Byron, and, frustratingly, no explanation of the random numbered placards scattered throughout at various unmemorable intervals. We had the requisite discussion about which hangs from the ceiling and which from the floor, stalactites and stalacmites, and decided that the ceiling protrusions were the ones hanging on ‘tite.” Again it was clear that the hobby of Greek youth is a destructive version of the art of their ancestors: graffiti. Either with charcoal or a black paint it seemed Greeks and others of all nationalities had covered almost every large and available rocky protrusion on the pathway with names and dates. Ashlie did get me to be amused by it once only by pointing out that some creative vandals had taken to backdating their entries by several hundred years, apparently deriving pleasure from the possibility of being confused with more storied explorers who had not, as they did, used railings and cement stairways to explore the reaches of the cavern.

We climbed out only to be accosted by a shirtless man demanding a photograph. Ashlie took the opportunity, after a five minute grace period, to express her disgust at the proliferation of shirtless tourists. The shirtless tourist had a scooter. I reminded Ashlie that I would have liked to rent a scooter — we could even borrow theirs. Surely his lack of shirt meant he wouldn’t be using it soon? Again she rejected my suggestion. Terribly disappointing. I’m sure we could have successfully navigated Paros and Antiparos on a scooter. Then again I was shortly thereafter provided persuasive evidence to the contrary: we rode in the first row of seats in the bus, peering out of the windshield with a mixture of horror and awe as our driver raced town-ward.

The bus left us off only slightly dizzied in town, and we browsed a bit then headed for the beach. It was curious, the opposite of the steep drop-off in Paros, because we waded out for meters and meters before it even got deep enough to paddle. Ashlie was complaining by the third mile — “When will it get deep??” — but I didn’t think it was too bad. Except for the smooshy things on the sea floor and the continued potential threat of sea urchins. Unless they’re on sushi or in a tank, I am not a fan of sea urchins. Okay, or, or, unless I’m wearing a wet suit and water shoes. And gloves. In a move totally out of character, we fell asleep again until 6:30 pm. We hopped a ferry back to Pounda — Poo, not Pow — and took a bus back to Siroco’s. Ashlie showered and prepared for dinner while I continued attempting to conduct business as though I was in Washington, DC, for the purposes of the campaign in Kyiv. On dial-up internet with a cranky Greek keyboard, of course. So then I rushed and showered and threw on a dress, and we left for the harbor to meet two of Ashlie’s friends for dinner. At dinner I finally got a thorough explanation of the spitting deal from My Big Fat Greek Wedding, the evil eye, and traditions of dispelling ill wishes.

Comments are closed.