Introductory Essay: Prologue to Creative Responses

please click the above link for a pdf of my introductory essay/prologue to blog posts (a cleaner looking version)

Introductory Essay for Blog Entries

In today’s world, given the turmoil that sometimes seems to be caused by religious differences, it is easy to see each religion as a monolithic entity existing separate from other religions, and thus representing starkly polar worldviews. Often, such notions arise as a result of not utilizing a cultural studies approach towards studying religion, which is arguably the best approach for understanding the role of religion in one’s daily life. The cultural studies approach, which examines the particular context in which one interprets his or her religion, is particularly important when it comes to understanding religions like Islam, whose adherents come from vastly different backgrounds. Through the cultural studies approach, which is arguably much more interdisciplinary than the textual approach, we see that one’s interpretation of religion is strongly influenced by factors including social, political, educational, and economic aspects of life, as well as one’s particular historical backdrop; this then makes the arts and literature a unique window by which we can observe a particular culture’s comprehension of the religion (Infidel of Love 10). These creative responses thus are my own response to my understanding of Islam, and intertwined in these works, then, are not only lessons from the classroom, but my own personal experiences, which have themselves been shaped by the economic, social and cultural backdrop in which I have grown up.

Asides from the different cultural backdrops in which one can interpret Islam, it is also crucial to understand the fundamental divisions that have persisted in Islam, from Sufism, Shi’a, to Sunni groups. Understanding these different communities of interpretation is thus crucial for comprehending Islam as a whole. For example, we have learned in class the centrality of the figures of Ali, Hussain, and Hassan in the Shi’a cosmology. This is manifested through the Shi’a tradition of the Ta’ziyeh, a passion play commemorating Imam Hussein and his family’s suffering at the hands of the Sunni caliphs. However, the Ta’ziyeh is certainly more than a ‘play’ as we define it in the Western tradition: simple and bare in its execution, the Ta’ziyeh is a metaphor for one’s worldly suffering, and has religious significance for participants, tying into the idea of Hussein’s role as intercessor in the Shi’a tradition (Chelkowski 2). The oppression of Shi’ites by Sunnis has certainly been an important theme in Islamic history, and I have attempted to address this in one of my creative responses, in which I have done a watercolor painting representing the important role that Imam Hussein plays for Shi’ites by depicting him as the setting sun. Thus, I have attempted to portray both the majestic nature of Imam Hussain while also illustrating his terrible fate, which has strong significance for the Shi’a. While the intercessory role played by Hussein and the controversies surrounding this is a manifestation of a main point of contention between the two primary communities of interpretation in Islam (that is, the Sunni and the Shi’a), it is important to remember that many other communities of interpretation exist even within these two main branches. Again, this ties back to the central theme of this class: the interpretation of Islam is just as diverse as its followers.

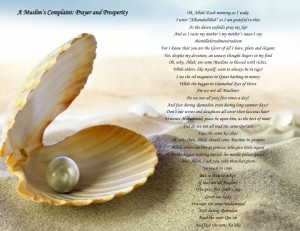

Despite the vastly different backgrounds that Muslims around the world come from, all Muslims share basic tenets, which include the Shahadah and the Five Pillars, which includes zakat, or the giving of alms. These pillars, while certainly not explicitly stated as such in the Qur’an, are an example of ritualization of religious practices, and foster for many Muslims around the world a strong sense of community (The Pillars of Islam lecture). The zakat is significant for its goal of fostering social justice, which is an important aim in Islam, by awakening in Muslims a spirit of social responsibility (The Pillars of Islam lecture). The issue of social justice in Muslim countries thus something I find particularly fascinating, and have attempted to highlight in my creative response in the form of a free verse poem, in which the speaker of the poem, who himself is a Muslim, forms a “complaint,” much like Muhammad Iqbal in Complaint and Answer to Allah inquiring about the impoverished state of many Muslims. In my work, I “ask” Allah why despite their devotion to Allah through ritual, some Muslims are not blessed with wealth and seem to never be able to escape poverty, while others live lavishly. Thus, I have also attempted to raise the question of what it means to have faith.

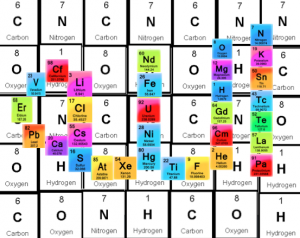

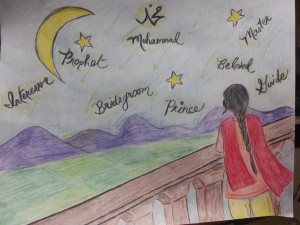

However, any discussion of Islam and its themes in modern society would be incomplete without discussing the central role of Allah and Prophet Muhammad. Certainly, the role of Allah as creator in Islam is one that all Muslims, regardless of their understanding of Islam, adhere to strongly; we see this strongly manifested in the 99 names given to Allah, amongst which are ones such as al-Muhyi (Giver of Life) and al-Mawla (Master) (Handout Week 4: The Qur’an on the Attributes of Muhammad and the Names of God). As a faithful Muslim, then, one must find in every semblance of creation a sign of Allah, and one example of this is the calligraphy of “Allah” that takes on many shapes and forms. As such, I have included in one of my creative responses a collage of “Allah” calligraphy constructed using the elements of the periodic table. As a student of chemistry, I find beauty in the organization of the universe through molecular bonds between atoms of various elements; as a Muslim, I see the diversity of elements and their unique organization into the periodic table as a manifestation of Allah. However, any discussion of Allah in Islam would be incomplete without discussing the role of Prophet Muhammad in a Muslim’s life. For Muslims the Prophet Muhammad’s life is a paradigm by which to live, and as such, one carefully studies the Hadith, which are known to contain many of his teachings. Muhammad shares many of the traits exemplified by the 99 names of Allah (Handout Week 4: The Qur’an on the Attributes of Muhammad and the Names of God), and in much of the literary and artistic responses seen around the Islamic world, the love for Muhammad is beautifully expressed. A particularly captivating example of this was in Sindhi poems, and their use the idea of viraha, so that Prophet Muhammad is represented as a beloved with whom his lover, usually a young woman, longs to reunite with (Asani 161). As such, in my creative response, I have illustrated how such a young virahini be, looking out at the moonlit sky for a sign of Prophet Muhammad, with whom she longs to reunite, and thus, end her separation from the divine.

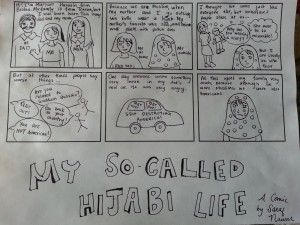

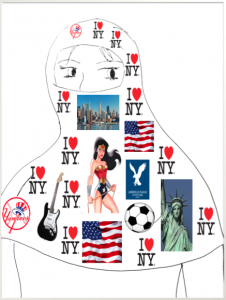

An important theme that we have discussed in class is that of women in Islam, and much of the discussion has centered on one item of clothing, the hijab. The theme of the hijab is well explored in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. The hijab has played a key role in debates surrounding various reform movements, ranging from imitative to Islamist, so that while the former attempts to embrace Western culture by making obsolete what is perceived as antiquated Islamic symbols, such as the hijab, the latter sees Islam as a means to create a nation state (Reform Revival Iran Lecture). The hijab, however, has become today a contentious issue for Muslims in both predominantly Muslim countries and in Western countries, such as the United States. For example, in westernized countries, women wearing the hijab are seen as symbolizing everything that is un-Western, and for us here in the U.S., perhaps ‘un-American.’ Some thus see the hijab as a manifestation of Islam’s oppression against the female gender. However, what we have learned from class is that the hijab, for Muslim women, is a means of expression not only of their religious beliefs, but also of their identity. Because of the importance of the hijab as a means of interpreting the Muslim identity in the modern world, I have focused two of my creative responses on the matter. One is a comic strip modeled after Satrapi’s Persepolis focused on a fictional hijab-wearing Muslim girl in the U.S. who feels that her identity as an American is overlooked due to her head covering. While she feels American, she and her family are labeled as “terrorists” because of their religion. The other piece is a collage, where I have shown a female Muslim New Yorker, who to an ordinary person, may appear to be just another Muslim woman, but in reality, is just as New Yorker, and American as anyone else. The latter fact, to some observers, may be obscured by her hijab, which is what I wished to convey. However, through the images in the hijab collage, I wanted to illustrate that her identity is constructed of far more than just her religion, and includes such things as sports, music, and fashion, to name a few.

Furthermore, we learn from our various readings, particularly Rokeya Hossain’s “Sultana’s Dream,” that the oppression of women is not always a result of religious standing, but often a result of a combination of factors, which include both prevailing cultural and political beliefs. In fact, as explained in class, Islam in many ways “liberates” women, with the Qur’an stating the equality of believers, regardless of gender, and with women playing a key role in the early history of Islam (Gender and Islam lecture). Yet, as Hossain’s short story seemed to suggest, it is still important to carefully examine and question the rights of women in such countries, and to take an active role in assuring that one’s rights are not usurped because of one’s gender, whatever the justification may be, such as religion. Again, we can go back to the idea of communities of interpretation when it comes to the role of women in Islam; whereas some have interpreted the Qur’an in its strictest readings as a way to oppress women, today, many Muslim women have interpreted the Qur’an as a means of regaining their rights, thus finding their needed solace. A particularly important figure espousing the latter interpretation of the Qur’an is Amina Wadud Muhsin, who believes that much of the oppression of women in Islam is a consequence of patriarchal interpretations of the Qur’an; however, by using the parts of the Qur’an that clearly speak for the equal rights of genders, she believes that it is possible for women to utilize the Qur’an to stop their oppression (Gender and Islam lecture).

Overall, I hope one finds these creative responses informative, and hopefully, at least somewhat entertaining. These responses themselves are my own interpretation of Islam, and in it, I have attempted to convey the diverse spectrum of beliefs found in Islam itself, as well as the plight of Muslims in the modern world. For a Muslim, clearly his identity as a follower of the Islamic faith is important, but certainly, his identity is equally carved by his own life experiences, and amongst these are one’s culture and history. One’s identity is also a product of one’s passions, and through the literature and arts, one can show not only one’s love for Allah and Prophet Muhammad, but also express themselves, just as I have done in my creative responses in this blog.

Works Cited

Asani, Ali. Infidel of Love: Exploring Muslim Understandings of Islam. Harvard University Press, 2013.

Asani, Ali. “In Praise of Muhammad: Sindhi and Urdu Poems.” Religions of India in Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Asani, Ali. Lecture: Gender and Islam. Aesthetic and Interpretive Understanding 54.

Asani, Ali. Lecture: Pillars of Islam. Aesthetic and Interpretive Understanding 54.

Asani, Ali. Lecture: Reform Revival Iran. Aesthetic and Interpretive Understanding 54.

Chelkowski, Peter. Ta’ziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran. New York University Press, 1979.

Handout Week 4: The Qur’an on the Attributes of Muhammad and the Names of God.

Hussain, Rokeya Shakhawat. Sultana’s Dream and Selections from The Secluded Ones. New York: Feminist Press, 1998.

Iqbal, Mohammad. “Complaint and Answer.” Trans. by A.J. Arberry.

Satrapi, Marjane. Persepolis. New York: Pantheon, 2003.